<1> Throughout 1897, a series of six full-page illustrations by Philadelphia artist Alice Barber Stephens (1858-1932) graced the covers of the Ladies’ Home Journal, reaching an audience that had swelled to nearly one million readers (Zuckerman 26). Collectively titled “The American Woman: A Series of Typical Sketches,” Stephens’s realistically drawn and painted illustrations mapped the changing roles of women in the U.S. in the post-Civil War decades, a period when thousands of women were leaving the confines of the private family home and entering the workforce.(1) Although the journal’s conservative editor Edward Bok preferred more traditional scenes such as The Beauty of Motherhood (fig. 1), he reluctantly acknowledged in an 1893 column that The Woman in Business (fig. 2) was “the subject of the hour” (18). Bok frequently expressed his ambivalence and even hostility toward the New Woman, declaring in his October 1894 column that women should occupy themselves “principally in the home . . . [where] woman’s influence is most potent” (18). A decade after Stephens’s images were published, her protégée Charlotte Harding (1873-1951) marked the ascendance of the career woman in illustrations for Collier’s for Eleanor Abbott’s short story about an unmarried cartoon artist. To emphasize the young woman’s inner drive and independence, Harding loosely sketched the figure of Noreen in the telltale ensemble of the “New Woman”—shirtwaist, tailored jacket, and skirt—striding determinedly across the magazine’s cover with her large red portfolio (fig. 3). Taken together, Stephens’s and Harding’s illustrations and Bok’s columns highlight some of the tensions in late nineteenth-century American society over shifting definitions of womanhood. More specifically, the images and texts underscore the challenges that female workers faced as they attempted to balance more traditional conceptions of femininity with the realities of the modern marketplace.

<2> Stephens and Harding were two members of, what Norma Bright dubbed, “the most important group” of women illustrators in the United States in 1905 (850-51). Based in and around Philadelphia, these female artists played a critical role in the promotion and sales of illustrated magazines during “The Golden Age of American Illustration” between 1885 and 1925 (Elzea 7-17). The widespread reproduction and popularity of their work derived in large part from the artists’ skills and professionalism, but also stemmed from their unique status as “women illustrators.” Writing in The Critic in 1900, art critic Regina Armstrong wrestled with the term, expressing concern that “it seems like putting up a target for further shafts by classifying such an art as that of illustrating by a title which designates a dignified portion of its workers as ‘Women Illustrators’” (“Child Interpreters” 417-18). Armstrong’s perceptive assessment alludes to the broader implications of this gendered characterization in the highly competitive and contested arena of American art during this period.(2) Faced with larger numbers of women entering art schools, many critics and commentators deplored the “specter of ‘feminization,’” which threatened to undermine the field’s standards and to violate normative gender roles (McCarthy 85; Burns Modern Artist 181-83). In her study of American women artists between 1870 and 1930, Kirsten Swinth demonstrates how efforts by male artists to distinguish fine art from mass art and to safeguard the realm of “high culture” (105) as a “masculine enterprise” (105) left women artists with diminishing prospects for the sales of their works, and relegated them to the “lesser arts” (105) of design and illustration (65-130). Further, as Michele Bogart has noted, even within the field of illustration, the influx of women provoked strong negative reactions among many male practitioners; their attempts to legitimize illustration as a serious “male and professional endeavor” presented mounting challenges to the acceptance and progress of women illustrators (30-31).

<3> This article examines how these issues of gender informed the artistic practices and strategies of Philadelphia women illustrators during this pivotal historic moment when art was becoming increasingly professionalized. As Laura Prieto has argued, in order to skillfully navigate the ever-changing contours of this crowded, male-dominated field, women artists had to carve out a distinctive “feminine professionalism” (2) that integrated the disciplined practices of art making with traditional, middle-class ideals of womanhood (1-8). At the outset, Stephens, Harding, and their female colleagues staked their claim as illustrators by pursuing formal art education and by cultivating contacts with major publishing houses, such as hometown giant Curtis Publishing. Perhaps even more valuable, however, were the strong networks women illustrators established during and after their student days, through which they acquired vital sources of personal and professional support, as well as important outlets for their work. Negotiating a delicate balance between their personal lives and public personae, their domestic spaces and studio environments, the women cultivated artistic identities that signaled education, talent, commitment, industriousness, and, above all, respectability.

“Ambitious Girls!”

<4> Stephens, Harding, and their female colleagues entered the workforce in the wake of the “magazine revolution” of the 1880s, when a dramatic upsurge in the number of illustrated periodicals brought about a radical “visual reorientation,” as publishers and editors increasingly relied upon the appeal of illustrations to boost their circulations and, in turn, attract advertisers (Harris 307).(3) The art of women illustrators, in particular, served as a vital conduit to the growing number of female readers and consumers. In his 1890 novel A Hazard of New Fortunes, author and former magazine editor William Dean Howells astutely noted these connections among gender, mass culture, and consumption. After declaring “that women form three-fourths of the reading public,” Fulkerson, Howells’s fictitious magazine syndicate man, advocates using women illustrators—“God-gifted girls”—to attract female readers (191).

<5> Commercial illustration, a blend of high art and popular culture, thus emerged as an enticing field that offered women marketable job skills, widespread opportunities for employment, and fairly well paid work. In her ruminations on women in the field of art in the early 1890s, critic and educator Susan Nichols Carter declared that “[a]mong new directions of art, pen and ink illustration furnishes a promising field. Newspapers and magazines are filled with many a sketch from the busy brain of a woman” (384). Frances Marshall, writing in the New York Times in 1912, similarly proclaimed that “[t]he artist who can express in her drawings the charm, the winsomeness of girlhood will find a ready market for her . . . . [Women illustrators] are wanted for magazines and book covers, for color pages, for illustrations, for advertising, for posters, for calendars.” As late as 1918, an advertisement for the Federal School of Commercial Designing promised “ambitious girls” the possibility of earning up to $75 a week and assured them “[i]n this modern profession you are not handicapped: you are paid as much as a man with the same ability. Women are naturally fitted for the work” (101).

<6> Despite the numerous optimistic predictions for their professional success, aspiring female illustrators needed tremendous dedication and fortitude to overcome resistance to their entry into the field. As Arts and Crafts designer Alice Morse advised in her essay to accompany the display of women’s art at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, it was essential for women to refute charges of amateurism and to demonstrate that they were not “following art in a dilettante spirit” (68). The first step toward professionalization was to pursue rigorous art education and training. Philadelphia women illustrators began their careers by enrolling in traditional art courses at either the Pennsylvania School of Design for Women or the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Stephens, Harding, Elenore Plaisted Abbott (1875-1935), Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935), and Wuanita Smith (1866-1959) were among those who initially enrolled at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (Elzea and Hawkes; SHP).(4) Touted as “the pioneer in industrial art training on this continent,” the school’s fine arts curriculum was revamped by the 1880s to include classes in composition, life drawing, and pen-and-ink drawing, which had replaced wood engraving in order to accommodate new methods of photoengraving (Walls 177-99). As Stephens outlined in “The Art of Illustrating,” under her tenure as an instructor there in the 1890s, students profited from a thorough grounding in the basics of academic instruction, including “work in all mediums,” and a strong basis in composition to train the illustrator “to express [herself] in a definite form and by a fixed time” (54).

<7> Many women sought additional formal academic instruction at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In 1876, Stephens enrolled at the Academy, where she studied with renowned artist and teacher Thomas Eakins. Others followed Stephens’s path to the Academy, including Abbott, Harding, Jessie Willcox Smith, and Wuanita Smith, as well as Ellen Wetherald Ahrens (1859-1935), Anna Whelan Betts (1873-1959) and her sister Ethel (1878-1956), Elizabeth Bonsall (1861-1956), Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871-1954), and Violet Oakley (1874-1961) (Elzea and Hawkes; SHP). Like many female art students of the day, most of these women had to finance their studies through paid work, such as fashion illustrations and advertisements for department stores, magazines, and newspapers (Cuba 4-7). Women illustrators profited from the Academy’s expanding curriculum and the tutelage of instructors such as Thomas Eakins, Robert Vonnoh, and Thomas Anshutz. After completing beginner classes, female students advanced to courses in composition, antique drawing, and, ultimately, life drawing classes (Pennsylvania Academy). For Eakins, the study of the nude human figure was crucial to one’s development as an artist. Stephens’s realistically modeled illustration The Women’s Life Class (1879; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts), which accompanied an article on Philadelphia art schools in Scribner’s, underscored the importance of this practice even for the Academy’s female students. Green studied with Eakins, drew in the life class taught by Vonnoh, and acquired from Anshutz “a frank and genuine knowledge of drawing and a love of those relics of antiquity” (Emerson). In his 1905 article for the Century Magazine, Harrison Morris, managing director of the Pennsylvania Academy, makes a point of establishing a clear lineage from its teachers to the group of successful Philadelphia illustrators, crediting the “thorough-going instruction” of the Academy’s faculty with the emergence of “the first distinctive American vein in art” in illustration (725).

<8> Ultimately, all of these women (with the exception of Stephens), along with Bertha Corson Day (1875-1968), Ellen Bernard Thompson Pyle (1876-1936), Sarah Stilwell (1878-1939), and Katharine Richardson Wireman (1878-1966) sought further practical instruction in illustration with renowned artist and illustrator Howard Pyle (1853-1911) at the Drexel Institute and, later, at his Chadds Ford summer school and Wilmington studio (SHP). Pyle preached to his students that illustration was “the art of the day” and assured them of the great demand for skilled illustrators (Day). Under his leadership, Drexel’s School of Illustration provided practical, hands-on instruction. According to the Year Book of the Departments, the curriculum encompassed all aspects of the illustrative process, from composition and the role of models to drawing techniques, mediums, and the use of color (24-25). In Pyle’s manifesto “A Small School of Art,” published along with illustrations by many of his female students in Harper’s Weekly in 1897, he ranked composition, intended “to teach the student to observe all the particulars in nature,” as the most important foundation (711). Ethel Betts praised Pyle’s composition class as “outstanding” and “wonderfully instructive”: each week students submitted original drawings for critiques and received helpful feedback from Pyle and other professional artists (Bains 12 Dec. 1946).

<9> Memory and imagination also played pivotal roles in Pyle’s approach to teaching illustration: as Bertha Corson Day recorded, Pyle explained to students that “in the academy you are taught to paint what you see—the art editor wants you to paint what you don’t see.” Day’s notebooks from her classes at Drexel confirm that Pyle skillfully translated the technical and artistic aspects of illustration to his students. Further, Pyle’s keen sense of the commercial market provided them with a nuanced understanding of how to interest audiences and win over art editors. Advocating “sincere spontaneous expression” and “suggestiveness,” Pyle emphasized the importance of imagination, feeling, and originality in illustration. In an interview later in her career, Thompson similarly recalled the inspiration Pyle infused into his students: “The sincerity of his own work and his unflagging enthusiasm affected everyone around him and made a deep and lasting impression on his students” (Parker 47).

<10> The School of Illustration appealed to new art students and professional illustrators alike. For women matriculating from both schools of design and academic art programs, such as Day, Harding, and Abbott, Pyle’s beginner courses offered the chance to cultivate a sensitivity for illustration and to learn the technical requirements to make a picture capable of being reproduced as an illustration. For women already in the workplace—Green and Jessie Willcox Smith among them—the Advanced Class for Professional Illustration provided not only technical criticism of their work, but also brought them into contact with some of the major publishing houses. Several students realized this ambitious goal of Drexel’s program with the publication of their original art. One of Day’s illustrations was published in the June 15, 1896, issue of the Chap-Book. In his letter of 23 June 1896 to Day, Pyle congratulated her on the acceptance of her drawing: “I hope you bear in mind what I have so often said in the class that to have a drawing accepted and published is a sure sign that the work is above average. There is no better criterion of fundamental excellence of work than to have it accepted and paid for by the Art Department of a magazine.” During her last year of study with Pyle at Drexel, Wireman earned her first paycheck for a cover design later published in the Saturday Evening Post (Shuttleworth and Holahan 6). This real-world experience was central to Pyle’s teaching philosophy: “You will learn more in one week of actual work to be reproduced in public print, than you can learn in two months of school study” (McDonald and Hinton 127).

<11> Female students also took advantage of Drexel student exhibitions and Pyle’s powerful network of contacts in the world of publishing to promote their work. Day, for example, used Pyle as a conduit to sell her illustrations to editors August Jacacci of McClure’s and Edward Penfield of Harper’s (Pyle, 25 Apr. 1899; Pyle, 25 Oct. 1899). According to the 1899 Catalogue of the Third Exhibition of the School of Illustration, students including Anna Betts, Day, Stilwell, and Thompson showed their original works intended for publication in popular magazines such as Collier’s, Harper’s Weekly, Harper’s Bazar, the Saturday Evening Post, and Scribner’s. Several of the pictures in the exhibition by Betts and Thompson were the result of a collaborative project to illustrate the serialization of Paul Leicester Ford’s novel Janice Meredith (1899) for Collier’s. The women’s drawings and paintings manifest the close attention to historical details of architecture, decorative arts, and costume advocated by Pyle, as well as the crisp delineation of forms that would translate well into halftone reproduction (fig. 4). In the review “Exhibit by Mr. Pyle’s Class,” one critic described this exhibition as “by far the most interesting exhibitions of art students’ work to be seen in this city,” and touted the fact that “nearly every picture hung has been reproduced and published in a magazine or weekly paper.”

<12> The Betts sisters, Day, Stilwell, and Thompson continued to profit from exhibitions of their works and from the successful marketing of their drawings to magazines at Pyle’s summer school of illustration, which he established near Chadds Ford following the 1897-98 academic year at Drexel, and, later, at his Wilmington studio (SHP). Ethel Pennewill Brown (1878-1960) and Olive Rush (1873-1966) also relocated to Wilmington to study with Pyle. Even though both women had attended the Art Students League in New York and were already practicing artists, Pyle’s teaching fine-tuned their techniques in illustration (Cuba 10-14).

A Sisterhood of Art in the City of Brotherly Love

<13> The women’s years with Pyle proved a vital catalyst not only for their artistic development and commercial success, but also for lifelong friendships that would provide invaluable networks of support. Many of the women established shared studios and living spaces, a common arrangement at the turn of the century that made their accommodations more affordable. Further, the combination of the refined, domestic settings of the women’s studios and their genteel lifestyles resulted in public identities that tempered their professional success with socially acceptable behavior.

<14> Classmates Ahrens, Green, Oakley, and Jessie Willcox Smith established shared home and studio space at 1523 Chestnut Street, where they created an environment wholly suited to their artistic production. In his 1902 article about Smith for the Book Buyer, Harrison Morris’s description of their Chestnut Street studio suggested the significance of these female bonds on the women’s public personae:

There is so much in common between the members of that group of very clever young women . . . that when you have said praiseful things of one you have said them at all. The kind of work with pen and brush they do, the training they have had, the aims they express, are close allied; and they live out their daily artistic lives under one roof in the gentle comradery [sic] of some Old World ‘school,’ a band of independent partners in talent who have no time for rivalries and who would admit none if they had. (201)

Morris infused their professionalism with a sense of genteel domesticity, and, in his estimation, the women’s daily artistic lives assumed great importance in the shaping of their public images.

<15> As Aimée Tourgée described in an 1897 article for The Art Interchange, Stephens’s Philadelphia studio was “characteristic of her earnest, unfanciful genius” and attested to the seriousness of the artist’s endeavors: “a large room, with no dust-accumulating frippery,” the space was filled with “solidly elegant” furniture fitting for her society scenes, a table “littered with books, prints, [and] the latest Salon catalogues” lit by a skylight from above, and “stretchers, rolls of canvas, portfolios, [and] sketches” (74). Despite its utilitarian contents, however, the atmosphere of the rooms was “all decorous, refined, potential” (Tourgée 74). Additional press coverage of the studio, which Stephens shared with Harding from 1899-1903, indicates how notions of feminine propriety permeated public perceptions of the artists:

The studio is a quaint room, with a low ceiling, built in the form of an L, and arranged with quiet good taste. It is an attractive workroom, with all the appointments necessary to the calling of its occupants, and when it is occasionally opened for a “studio tea” it is frequented by all the artistic community of Philadelphia, who admire Mrs. Stephens as much for her pleasant personality as for her professional attainments. (Sheafer 246)

Articles typically coded the studios of women artists as “feminine” through the use of descriptive terms such as “homelike,” “cozy,” and “domestic” (Cooper 466; Fowler 212, 214). In the eyes of many writers, these studios served as not only workplaces, but also as extensions of the domestic sphere—sites where art intersected with graceful living and standards of feminine decorum, and where the somewhat non-traditional lifestyle of the woman illustrator could coexist with earlier nineteenth-century ideals of American womanhood.

<16> Other Pyle students established similar shared spaces in Philadelphia and Wilmington. Brown and Rush shared a studio in Wilmington at Tusculum, a boarding house and well-known gathering place for women artists. Between 1904-06, the two women attended Pyle’s Monday evening composition classes, during which he regularly critiqued students’ work (Cuba 14). In 1910, when Pyle left for Italy, Brown and Rush lived in his Franklin Street studios. Brown’s diaries chronicle her enduring friendship over the years with both Rush and Harriet Roosevelt Richards (d. 1932), another Pyle student, and confirm the importance of these female networks for the artists’ personal and professional lives. Brown’s entries are peppered with mentions of the other illustrators in conjunction with outings and social engagements, such as trips to Philadelphia to visit the Pennsylvania Academy, art exhibits, and restaurants.

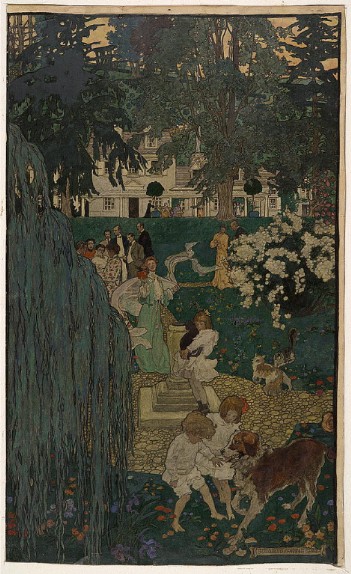

<17> Green, Oakley, and Smith relocated their home and studio in 1900 to the picturesque Red Rose Inn in Villanova, which reified the linkages among femininity, domesticity, and their artistic identities, and also contributed to the women’s fame in the region. There, the “graceful surroundings of country life” connoted a genteel lifestyle intimately linked with the refining influences benefits of nature (Humphreys). In her article on the Red Rose Inn, Mary Tracy Earle proclaimed that the artists’ move to the country, away from “the dry-rot of discouragement, which infests some studio buildings,” supplied a “mental tonic” for the “tired brain” (282). In Life Was Made for Love and Cheer, Green’s painting which accompanied Henry Van Dyke’s poem “Inscriptions for a Friend’s House” in the September 1904 issue of Harper’s Monthly Magazine (fig. 5), the artist deployed flattened forms, bold outlines, and rich colors to create an elegantly patterned composition that highlighted the beauty of the natural landscape and confirmed the artists’ respectability, decorum, elegant lifestyles, and good taste. Stephens also left the city, moving to Rose Valley with her husband, where their “picturesque” and “extremely artistic” Arts and Crafts house signaled the couple’s commitment to handcrafted objects and created a refuge from the ugliness of industrialization (Priestman).

<18> Although their domestic environments cultivated images of artful lives and feminine propriety, the home-based suburban studios of Green, Oakley, Smith, and Stephens were efficient, organized, and utilitarian. The ornate, cluttered Victorian furnishings of their earlier, heavily decorated Chestnut Street studios were replaced by clean-lined furnishings and the accoutrements of busy artists. Their shift away from earlier ornate spaces to more spartan, functional studio interiors is indicative of the large-scale demise of the sumptuous studio among American artists at the turn of the twentieth century. The transformation of their studio spaces from genteel settings to more functional “workshops” may also have signaled an effort by women illustrators to shed the trappings of feminine domesticity—“ornamental” and “decorative” rooms—for “sincere” and “authentic” symbols of masculine professionalism (Kinchin 12-29). Photographs of the women in their simply furnished, efficient studios (fig. 6) validated the women’s artistic integrity. Any notions of irrationality or female dabblers were dispelled by the tidy workrooms of hardworking artists. Descriptions of the studios of Smith, Oakley, and Green at their subsequent residence “Cogslea” in Mt. Airy bear out these gendered associations. A 1917 Good Housekeeping article on Smith declared that her “great studio” was “spacious, high-ceilinged—essentially the room of a big mind” with a “sense of repose and power” (25). Similarly, critic Charles Caffin characterized Oakley’s studio as “a workshop such as any man-painter would be glad to own, and arranged as he would have it, if his work were the main thing he kept in view. . . . the air of the place is one of practical and sincere work” (473).

<19> After years of formal art education and establishing their studios, Philadelphia women illustrators took yet another important step in cultivating their brand of “feminine professionalism” by joining the Plastic Club, a women’s arts organization founded in 1897 that proved tremendously valuable to these ambitious young artists. Like many women’s art clubs of the period, the Plastic Club aimed to remedy the growing disparity between the increasing numbers of women artists and the dwindling chances to exhibit their work, and to combat the isolation of artists in the modern world. According to its Constitution and the Plastic Club First Annual Report, the club mounted an ambitious schedule of annual programs—ranging from lectures and exhibitions to teas—“to promote a wider knowledge of Art, . . . to advance its interests by means of social intercourse among artists,” and “to bring the work of [its] members into the light.”

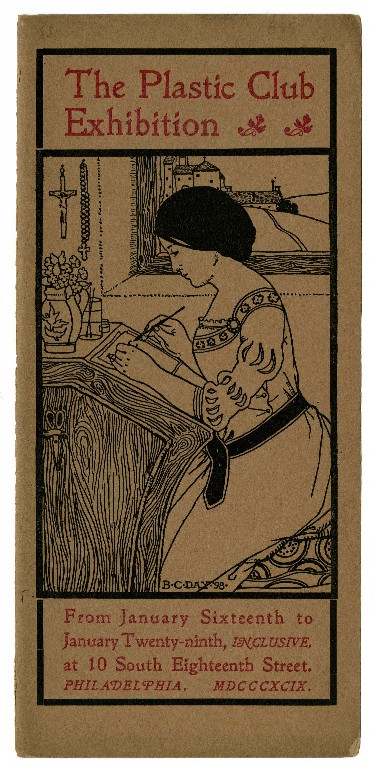

<20> Most Philadelphia women illustrators were active members of the Club, participating in its exhibitions and assisting the efforts of the Committee on Design, which, according to Jessie Willcox Smith’s notes, offered “productive help and experience to any who are desirous of working for reproduction.” Members’ designs for exhibition catalogues, advertising posters, and placards typically projected a vision of the female artist that signaled professionalism, but also conformed to middle-class ideals of femininity. Day’s cover for an 1899 exhibition (fig. 7), for example, features a female manuscript illuminator intently at work in seclusion from the outside world. The crucifix and rosary beads hanging on the wall reinforce associations among the artist’s femininity, piety, and domesticity. The Club’s promotional materials received ample coverage in the local press and newspapers frequently reproduced posters and placards along with reviews from critics.

<21> For the artists, however, the real strength of the Plastic Club resided in its numerous exhibitions and widespread press coverage. After the Club’s opening, writer Margaret Hamilton Welch predicted in her columns for Harper’s Bazar that the Plastic Club was “destined to become famous” due to its “interesting and significant” exhibitions. As the Plastic Club’s numerous exhibition catalogues indicate, women illustrators presented both original works and reproductions in major annual exhibitions, as well as small group and one-woman shows dedicated to work in black and white, work in color, and illustration. Reviews appeared regularly in newspapers in and around Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and other cities, raising the profiles of these women on local, regional, and national levels. As one commentator remarked in the Philadelphia Press of 27 November 1898: “The Plastic Club fills a not unimportant place in the art world of Philadelphia, and fills it well. The exhibitions always have serious intent as well as artistic content. As craftswomen in various fields conscientiousness is the note of much of the work done and a devotion to high ideals.” A reviewer of the Club’s Second Annual Exhibition of Works in Black and White for the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1898 seized upon the industry, artistry, and commercial success of artists including Green and Stephens, noting that they were “all practical workers, who [were] kept constantly busy with orders for prominent publications.”

“Commercialism with a big C”

<22> Although Philadelphia women illustrators bore all the hallmarks of professional artists as they launched their careers at the turn of the twentieth century—formal education, functional studios, and steady, paid commercial projects—they continued to face the implications of being “women artists” in gendered perceptions and language about their careers and art. According to many artists, critics, authors, and publishers, women were “especially fitted” to illustration due to their “temperamental equipment”: a “peculiarly feminine” point of view, a “sympathetic touch,” an innate “sense of decoration,” “delicate sensibilities,” a “natural adaptability,” and “woman’s intuition.”(5) Critics of exhibitions of women illustrators’ work lauded the artists’ professionalism, but continued to invoke a highly gendered language to describe their original illustrations as “delicate,” “graceful,” “quaint,” “daintily colored,” “spiritually suggestive,” and “imbued with delicate sentiment.”(6)

<23> Given their “feminine” point of view and “delicate sensibilities,” certain subjects and styles were deemed particularly appropriate for women illustrators. Writing in the early 1890s, Frank Linstow White remarked that for “the woman element” in the field of book illustration, “the delineation of scenes from child life” was “a specialty that would seem to appeal very forcibly to the woman artist” (6). In her article on women illustrators as “Child Interpreters,” Regina Armstrong asserted “many publishers hold that certain qualities of pictorial interpretation are distinctly the faculty of women’s delicacy and insight to portray, and especially is this true of the studies and compositions depicting child life” (427). Critics also identified a feminized “decorative tendency” in much of the work of women illustrators, including Betts, Green, Harding, Oakley, and Smith (“Three Women Artists”) (see figs. 7 and 8). According to Bailey Van Hook, the decorative—characterized by bold outlines, large fields of color, and arrangements of lines and shapes for “beauty and harmony of effect” (170)—was intimately linked to “a preoccupation with ‘beauty’” (159) in American art at the turn of the century and frequently employed to depict passive female and child subjects (159-85). Writing about Philadelphia artists for the Century Magazine, Harrison Morris stated that the city’s many women illustrators shared a “feminine personality” and “a common core of decorative treatment,” which “len[t] themselves so much better to a magazine page than the portrayal of frank personality and conventional landscape” (731). In Morris’s estimation, the decorative thus assumed a gendered dimension, one that inherently linked female illustrators, a “feminine personality,” and “the magazine page,” thus effectively distancing the women from distinctive masculine styles and high art.

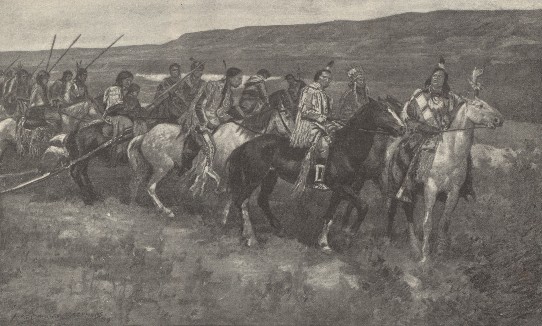

<24> Faced with these appraisals of their professional identities and their work, Philadelphia women illustrators adopted a variety of strategies to promote their art in the marketplace. Many of the artists attempted to professionalize by expanding and diversifying their artistic production, following Izora Chandler’s advice in What Women Can Earn (1899): to master a variety of styles and techniques suited to the new halftone and color printing processes; to strive for great accuracy of detail; and to campaign aggressively for work (223-24). A strong work ethic and a willingness to collaborate with editors and authors helped as well. Stephens and Brown, for example, adhered to rigorous schedules and went to great lengths to achieve accuracy in their illustrations through the use of models, backgrounds, props, and preparatory studies. In articles about Stephens for the Brush and Pencil and Quarterly Illustrator, both F.B. Sheafer and Frederick Webber, respectively, praised the artist for working as hard as a businessman and also appreciated her attention to innumerable details of her subjects. Stephens’s close study of settings and costume, along with her mastery of composition and drawing, led to commissions for more “masculine” tales of mystery and adventure. In a letter to the artist, Arthur Conan Doyle rated her illustrations for his Stark Munro Letters among the best he had ever had. Author W. A. Fraser similarly gushed about Stephens’s “marvelously correct . . . detail” and “artistic grouping” in her illustration for his story about Canadian native peoples, for which Stephens may have drawn on her husband’s extensive collection of Native American artifacts (fig. 8). As the Curtis Publishing Company’s remittances from the mid-1890s into the early twentieth century show, Stephens executed nearly 100 projects for the publisher, for which she received payments ranging from $125 to over $200 per project; her annual earnings from this publisher alone totaled between $1,000 and $2,000.(7) Brown’s disciplined studio practices also helped her achieve great stylistic versatility; her work ran the gamut from precisely rendered black-and-white charcoal illustrations to more broadly painted full-color illustrations. Brown was equally driven in her constant searching for work. Her diary entries chronicle numerous trips to Philadelphia and New York, where she pitched her illustrations to numerous art editors and often secured commissions for future projects. Although her earnings fell within the range that Chandler had forecast ($15-50 for drawings “of size and consequence” and $100 paid by a few magazines), Brown struggled to support herself and endured financial hardship for many years. In her diaries, the artist frequently lamented her lack of funds and fretted over how to find suitable studio space with “so little money.”

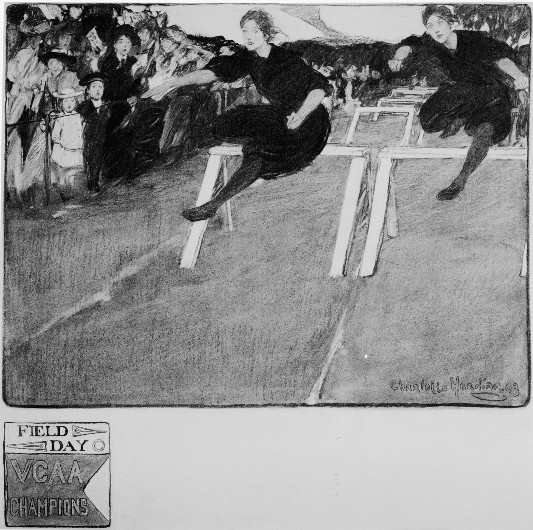

<25> Like Brown and Stephens, other American women illustrators also went to great lengths to research details about their historical and ethnological subjects, often clothing their models in historic costumes and traveling around the country to infuse their works with authenticity. Green conducted extensive preparatory studies and meticulously detailed sketches for many period stories, and frequently used photographs as aides-mémoires to achieve a high degree of realism in her subjects’ poses, garments, and props. Following her travels to Massachusetts, Washington, D.C., and Lancaster, Pennsylvania, between 1901 and 1905, Harding worked up illustrations on a variety of subjects for several different magazines, including a story about the Mennonites for McClure’s and an article about women’s college athletics for the Century (Bright 849). For the latter project, Harding’s boldly sketched charcoal drawings pulse with the movement, energy, and rhythm of female athletes in motion (fig. 9).

<26> The most commercially and financially successful Philadelphia women illustrators, however, translated their perceived affinity for feminine subjects (childhood and motherhood) and styles (the decorative) into lucrative projects for magazines, print publishers, and advertisements. Smith, for one, blended an aesthetic of cuteness with a decorative style in her pictures of mothers and chubby, rosy-cheeked children resulting in highly sentimental images that aroused strong emotions in viewers (fig. 10). The artist produced more than 180 cover illustrations for Good Housekeeping alone, earning between $1500-1800 per cover (Schnessel 135). Millions of magazine readers and subscribers collected Smith’s illustrations and prints with great zeal, expressing admiration for her tender scenes of motherhood and childhood and for her artistic skills, including her “mastery of color,” “good composition, sound drawing and solid qualities of taste” (Morton; “Colorings”). The widespread appeal of Smith’s art made her one of the most highly sought-after female illustrators. William Patten, a former art editor at Collier’s considered her drawings “one of [the magazine’s] most popular bids for circulation increase.” By specializing in typically feminine subjects and the feminized aesthetic of the decorative, Smith’s commercial success rivaled that of her male colleagues such as Harrison Fisher. According to the article “Modern Picture Making,” published in the Philadelphia Public Ledger in February 1910, Smith, Green and Stilwell were “well up in the wage scale,” with annual salaries ranging from $10,000-12,000. The three artists illustrated hundreds of stories and covers for Curtis publication’s Ladies’ Home Journal and Saturday Evening Post in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with fees from $25 for headings to $125 for cover illustrations, as recorded in the Curtis Publishing Company’s Remittances.

<27> Other women artists also cultivated longstanding relationships with magazines that cemented the popular appeal of their art and provided them with a steady stream of commercial projects. Both Thompson and Wireman continued to work after their marriages, successfully juggling careers with motherhood. After the death of her husband in 1919, Thompson Pyle resumed her career, working every weekday in her studio and frequently using her children as models for her illustrations, including covers for the Saturday Evening Post (Smith and Schiller 19-31). Wireman labored in her Germantown home, where she worked from early in the morning until dinnertime, nearly seven days a week. She made a good living as an illustrator, eventually supporting her family with a variety of projects including fashion pages, magazine covers, story illustrations, and advertisements for magazines such the Ladies’ Home Journal, Saturday Evening Post and Country Gentleman (Shuttleworth and Holahan 10-12, 17-27). Both women drew upon their own lives and experiences for their depictions of motherhood and childhood, such as Wireman’s tender portrayal of a young boy and his grandfather for the December 16, 1916, cover of The Country Gentleman (fig. 11). Wireman’s careful modeling of the two figures and their expressive faces, along with her finely rendered details of the toy steam engine, result in a highly realistic scene that is punctuated by bursts of red in the wrapping paper, the boy’s tie, and the Christmas tree decorations.

Katharine Richardson Wireman (1878-1966)

Oil on illustration board

24 1/2 x 20 3/8 in. (62.2 x 51.8 cm)

Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Sharon S. Galm, 2011

<28> Although most of these women illustrators achieved great commercial success and popular recognition for their depictions of childhood and motherhood, this success came at a price. It further solidified the gendering of the artists’ productions as the inevitable result of their femininity and their “natural” suitability for certain subjects. Their female counterparts in the realm of fine art experienced a similar bias: critics, commentators, and dealers repeatedly positioned the works of Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) and Mary Cassatt (1844-1926)—two of the most successful American women artists of the period—as the products of their distinctly “feminine” point of view (Ivinski 423-30). Such associations posed a risk to female artists’ integrity at a time when the battle lines between high and low art were being more sharply drawn. As critic Charles Caffin asserted in his 1910 article “A Painter of Childhood and Girlhood,” the linkage between an artist and the theme of childhood “[raised] in many minds a suspicion of his quality as an artist. For there is no easier way to snatch the bubble of reputation, and no other subject on which so much flimsy art and saccharine or meretricious sentiment have been expended” (922). Caffin’s quote aptly summarizes the hierarchies of gender, genres, and media that were solidifying in the U.S. at the turn of the twentieth century in both the critical discourse and the art market. As J. M. Mancini has argued in her study of early American modernism, in their attempts to professionalize the field of art and to elevate its standards, art writers, critics, and dealers valued esoteric subjects, abstraction, and unique art objects, and delegitimized sentimental, narrative themes, representational styles, and mass-reproduced images. The work of women illustrators was thus increasingly marginalized due to the gender of the artists and the commercial nature of their work.

Conclusion

<29> Looking back on her career as an illustrator, Ethel Franklin Betts recalled that she and her female colleagues entered the field “at the time color illustration was reaching its height and came into full flower” (Bains 30 Nov. 1946). Close study of the lives and careers of Betts and her female colleagues affords an excellent opportunity to analyze the unique set of circumstances that coalesced in the late nineteenth century to “make Philadelphia the city of women illustrators,” and to more fully comprehend the scope of women’s art activities and professionalism at this critical juncture on the brink of modernism (Armstrong, “Character Workers” 49). While scholars continue to forge new paths of inquiry into the roles of women artists and the popular press in the formation of class, racial, gender, and national identities, studies of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American art have continued to privilege modernity and modernism as masculine and as manifested through “high” art.(8) By examining an aspect of modernity that shaped the lives of millions of readers at this time—illustrations by women illustrators in popular magazines—historians of American visual culture can contribute toward what feminist literary critic Rita Felski has described as a “breaking down [of] traditional distinctions between a radical [masculine] avant-gardism and a mass culture that has often been depicted as sentimental, feminine, and regressive,” and advance a “retheorizing [of] the modern” (29).