<1> It took 28 years after Nathaniel Hawthorne published The Scarlet Letter in 1850 for Mary Hallock Foote to render drawings for one of the novel’s first illustrated editions, which was probably the first ever to be illustrated by a woman.(1) It took 130 years after the publication of Foote’s illustrated edition in 1878 for Project Gutenberg to digitize and disseminate Hawthorne’s novel with Foote’s illustrations.(2) It has taken seven years for Hawthorne scholarship to commence addressing and examining Foote’s edition, and theorize what her drawings suggest about the act of seeing, for the heroine’s audiences in the book, and for the author’s audiences reading the book.(3) This essay is one of the first to seek to recreate this 1878 dialogue between a male author and a female illustrator, and to assess how it implicitly alters the conversations within Hawthorne’s novel, about how men and women like Arthur Dimmesdale and Hester Prynne see one another, as well as how they each cope, in turn, with being seen.

<2> Foote’s illustrations would be superseded by photography, by the silent-film and the motion-picture adaptations of Hawthorne’s work, and by the Lacanian gaze theories that, to this day, inform the novel’s critical reception.(4) Antedating cinematography, Foote’s pictures were first conjoined to Hawthorne’s prose when graphic-arts images were just beginning to occupy spaces in published volumes, decades before cinematic images began flickering on screens. Attempting to recreate Foote’s original, pre-cinematic mode of marginal, visual authorship, I resist superimposing latter-day visual regimes and technologies upon her, and revisit instead the tools Foote actually had to work with—pen and ink on canvas—for visualizing Hawthorne’s character. Coinciding with Hawthorne’s prose, Foote’s pictures also omit, even tacitly censor some of the novel’s prose descriptions. Asserting her authorship within the margins of Hawthorne’s text, Foote does not anticipate intrusive, camera-like surveillance; she makes reader-viewers aware of the gendered dynamics of seeing and appropriately, not seeing Hester Prynne. Foote finds modes for hiding Prynne from the judging eyes of embedded audiences as well as reading audiences, even as Foote’s edition facilitates increasing visibility for the scenes of Hawthorne’s novel. Foote’s added visual dimensions in fact disable viewers’ judgments of the heroine, as they resist the increased exposure that could have come with the graphic illustrations’ newly enabled visions.

<3> Opening chapters are predicated on not seeing the heroine, even as we read about her. Other audiences in the book, who can see her, read her judgmentally and condescendingly on sight. Hawthorne’s romance takes it for granted that graphic arts will not occupy readers’ visual fields—until Foote adds visual dimensions. His narrative inhibits intrusive, voyeuristic visions—until Foote’s illustrations were added. Her arts enter the text, paradoxically, not to enhance photographic vision or Lacanian sight, but to sketch respectful screens around Hester, which Hawthorne’s embedded Puritan audiences within the book pointedly do not respect. To read this early, illustrated edition of Hawthorne is to prize Foote’s graphic-arts glimpses and to appreciate the omission of potential illustrations. To view Foote’s illustrations is to know one sympathizes most when one has learned not to scrutinize Hester as though one sees her through a camera, but to understand and empathize by kindly looking away from Hester. Foote redraws Hester faithfully for this new edition, but she reconfigures customary, judgmental visions of Hester at the same time. Without interrogating family dynamics, Foote’s work reinforces domestic constraints. Without protesting prevailing, sexist circumstance, her illustrations highlight women’s fortitude. Without fully excusing Hester Prynne’s transgressions, her images accord the heroine discreet, respectful privacies within the margins of a novel otherwise dominated by prying, puritanical eyes.

<4> Before Foote’s and others’ illustrative interventions, the novel’s earliest readers had seen only one of its images graphically represented. The author asked his original publishers at Ticknor and Fields for a “red-letter edition.” A single, crimson “A,” therefore, adorned early copies. An author’s frontispiece commenced later editions. An Illustrated Library of the major romances began appearing in 1871. By 1877, the Hawthorne family’s original copyright expiring, “James R. Osgood & Co., a successor firm to Ticknor and Fields,” Michael Winship writes, “issued the first new separate edition of The Scarlet Letter” (424). With Foote’s “rather lavish illustrations,” Winship tells us, “this was an expensive volume at $4 in cloth, $9 in leather” (424). As one of the book’s first female illustrators, Foote worked to secure the copyright, but she did not remain alone for long: “In 1879 Houghton, Osgood & Co., another successor firm, issued for $10 F. O. C. Darley’s Compositions in Outline from Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter, a series of 12 illustrated prints, each accompanied by a page of text extracted from Hawthorne’s work” (Winship 424). Hawthorne’s romance gained these adornments in the mid-nineteenth century’s golden age of illustration. Copyright claims continued generating rivalries. Though she was Osgood’s agent for visualizing Hester Prynne and retaining copyright, Foote would also experience her own, distinguished career, illustrating others’ works, and then becoming a prolific author-illustrator in her own right. Though she became a pioneering artist of Western imagery, she consistently self-deprecated in her writings, correspondences, and encouragements of other artists. She inspired the women artists and authors who came in her wake, but she remained opposed to women’s suffrage.(5) The subject of Wallace Stegner’s The Angle of Repose (1971) —itself the subject of Sands Hall’s plagiarism drama Fair Use (2001)—Foote still figures fascinatingly in our histories of the Wild West, women’s artistry, and pen-and-ink illustration.

<5> This heroine, Hester Prynne, and this artist, Mary Hallock Foote, in fact, feature odd parallels, eerie correspondences. If the heroine moved early in her marriage to a location just emerging from the wilderness, the artist similarly moved in the early days of her marriage to California’s remote mining camps. One found herself in that wilderness without her husband. The other had to have worried about feeling abandoned in a desolate, far western frontier. “No girl ever wanted less to ‘go West’ with any man,” she said of herself and her husband, Arthur DeWitt Foote, “or paid a man a greater complement by doing so” (Reminiscences 114). One raised Pearl in a foreign, sometimes hostile context. A family friend, the other wrote, “found . . . Lizzie Griffin, a young Canadian of English blood who had every requirement” for modeling the character for the illustrations, “including a babe in arms. The baby seemed providential: Hester Prynne must have a child” (Reminiscences 115-16). The baby was not the only facet of the novel for which Foote had to find a model. Hester Prynne turned her needle into a conventional means of suggesting unconventional ideas, and Mary Hallock Foote was a conventionally dutiful wife and mother, whose prolific western illustrations earned her a reputation as an admired novelist and short-story writer. In her Grass Valley, California home, Foote said she was “deep in my Scarlet Letter drawings,” receiving woodblocks from a Boston engraver by mail, and “not neglecting the daily walk for exercise and in search of backgrounds” (Reminiscences 126-28). Foote and other women artists of her day, according to April F. Masten, probably felt “annoyed by editors’ specifications” which accompanied orders for illustrations, since these specifications “could fluctuate between unchallenging topics and ridiculously difficult tasks” (194). “[D]espite their grumbling,” illustrators such as Foote “knew they were given difficult scenes to design because editors believed they excelled in creating the desired effects” (Masten 194). By October, 1876, she sent the first blocks of the series to the engraver A.V. S. Anthony and to her lifelong friend Helena de Kay Gilder, entreating her, “As you love me, you must try to judge honestly and tell me what you think” (Miller 49). She chose her own scenery, and posed her friend’s child however she wished as a model for Pearl. She rendered an image for each of Hawthorne’s 24 chapters, dispatched images thousands of miles to Boston, and thereby retained a degree of autonomy over her own commercial imagery. She finished her Hawthorne images just before the birth of her first child (Miller 49). In another possibly “providential” coincidence, she was the illustrator of a man, the new wife of a man, and the mother of a baby boy—who were all named Arthur. Foote, who would have grown up reading The Scarlet Letter, may well have entered into the task of illustrating it through an imaginative commiseration—not with the author, but with the heroine.

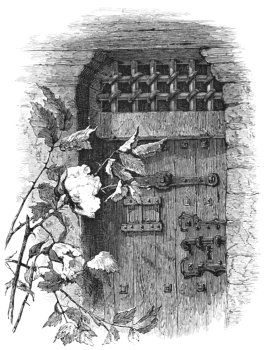

<6> Closely reading Hawthorne’s prose with Foote’s illustrations means foregrounding Foote’s attention to the heroine’s visibility and to the story’s visual politics. Though the added visual dimensions afford Hester Prynne more potential appearances before reader-viewers, Foote discreetly hides Prynne from what could have been the illustrated work’s multiplying, prying eyes. Foote delays her depiction of Hester until after three other, less interesting illustrations.(6) Depicting the structure of the Custom House from the outside, Foote implicitly obeys the narrator’s indications that women were unwelcome within. She accords with his suggestion that the only feminine presence in the government structure is an insignia of an eagle on the side of the building. Foote renders a wild rose that partly obscures the stern frame of the prison house door, the flower’s white color contrasting with the solid door’s darker hues (figure 1). “We”—says the narration’s royal “we”—“could hardly do otherwise than pluck one of its flowers, and present it to the reader” (Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter I: 48); Foote, following suit, has the flower interrupt the picture, extending from the page and to the reader, reversing the expected etiquette of who gives flowers to whom. If bachelors traditionally bestow them on maidens, the narrator’s proffered rose to the reader, according to Suzan Last, gives the reader impetus to “read as a woman,” “resists over-thematizing the story in a masculine manner,” and “privileges a ‘poetic truth’ of romance rather than historical realism, and a feminine perspective rather than a masculine one” (355). Readers of Foote’s edition, receiving a woman artist’s flower, are doubly feminized, courted with a bouquet and conspiring with a fellow, feminine reader. Foote’s flower, objectified on the page, also renders realistic and “masculine” what Hawthorne leaves sketchy and romantic. The text depicts the hearty “gossips” who judge Hester harshly before her actual issue from the prison, allotting space in proportion to each Goodwife’s malice in calling for Hester’s branding, banishment, or execution. Though readers may first flip forward to see depictions of the heroine, the first images merely delay, much like Hawthorne’s prose, Hester Prynne’s initial emergence.

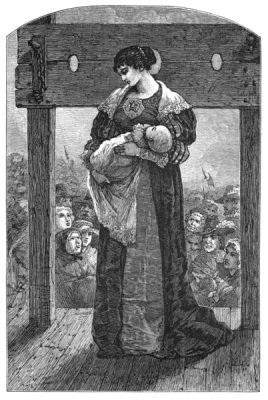

<7> Foote’s first rendering of Hester visualizes the regal bearing of a woman likened to a “statue of ignominy” (Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter I: 74; figure 2). Hester’s “A” actually seems small on her chest, absent of any scarlet color in a black and white image, and proportional to the shawl on her shoulders, the babe in her arms. If Pearl and the “A” seem to be equal marks of shame in the chapter’s prose descriptions, Pearl dwarfs the letter in Foote’s rendition. Hester’s flowing gowns, maternal attitude, and embrace of her babe commence associations with the Renaissance Madonna, which will last throughout the book. The scaffold, with holes for the penitent’s head and hands, forms a second set of frames for Hester, and we view her from a perspective distanced from that of the townsmen. They look up at her from behind, their expressions telegraphing scorn and jeers. Our perspective, level with Hester’s and framed by the scaffold, is guided implicitly by the prison-house doors: Foote’s rendering of the door in the earlier image tops it with a gentle, curved arc as we look at it. Now, we see Hester with that same, curved arc at the top, as though, in this later image, we are meant to be looking out ofthe same prison door. We see Hester, not as though we are judgmental Bostonian viewers in the crowd, but as though we are fellow prison-house inmates, looking out at the town’s ongoing pillorying of Hester. We are distanced from the Goodwives’ contumely, cast in guilty shadows, invited to feel we share the shame and penitence of a Madonna-like Hester, rather than empowered to pass judgment upon her.

<8> Though Hester spends almost all of chapters 2 and 3 exposed to public view, the letter all-too visible, Foote renders her at the final moment of the latter chapter’s action, away from that audience’s prying eyes, the letter illuminating the interior of the prison space instead. Sketched, slanted lines flank her, mediating the letter’s phosphorescence and the wall’s darkness, making it clear we glimpse Hester when the crowd does not (after her return to the prison house) and as the crowd does not—with her letter obscured, her physiognomy pensive, her guard down, as it were, after the long hours of public trial. Foote does not render Hester as Roger first sees her from the crowd, nor as Arthur half-heartedly urges her to name her baby’s father. She departs from the relentless scrutiny of the early chapters: she privileges intimate over public views; minimizes, rather than exaggerates, the letter as a badge of shame; and separates sympathetic readers from sanctimonious viewers.

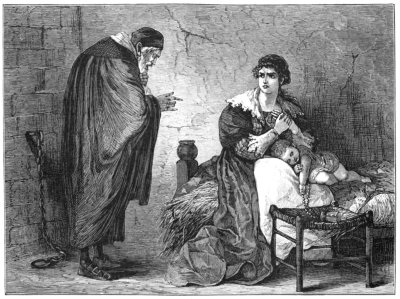

<9> Images for subsequent chapters present Hester with her letter almost always obscured, as they allow her to share spaces with Roger, rendered here as a stooped Quasimodo (figure 3). Caped and capped, he extends toward her an accusatory finger, as her hands fold over her emblem, and above her babe. The babe is almost an extension of Hester: Pearl’s arm, pointing down, seems difficult to distinguish from Hester’s limb. Pearls dangle in the image, below a girl named Pearl. The shackles on to the wall to Roger’s left, repeating this motif of dangling pearls, speak of confinement, much more than does the letter, which Hester hides and Foote deemphasizes. Foote also renders the moment at which Hester “dropped her work upon her knees, and cried out with an agony which she would fain have hidden, but which made utterance for itself, betwixt speech and a groan,—’O Father in Heaven,—if Thou art still my Father,—what is this being which I have brought into the world!’” (I: 96; figure 4). Her kneeling pose hides her letter, and privileges a repentant, maternal Hester to the proud “hussy” whom viewers in the novel (in contrast to viewers of these illustrations) think they see. The effect in these renderings is a much more modest Hester, subordinated visually to the other characters, placed in private, interior spaces, and often obscuring the single, red letter that is supposed to dominate the prose.

<10> Foote’s scenes of Hester’s visit to Governor Bellingham showcase her interactions with family members, and highlight characters’ degrees of visibility, for Puritan viewers and reading audiences. Foote does not depict the moment in which Hester and Pearl look directly into the soldier’s breastplate in the governor’s mansion and see the “A” rendered gigantic in a self-portrait in a convex mirror, as it were. She renders the moment presumably just before that, from a different vantage point, as Pearl first draws Hester’s attention to the breastplate (figure 5). The posture implied by the helmet and armor repeat Hester’s carriage, her cape, letter, and bonnet almost making the “A” an equivalent, armorial insignia. Her letter, forming a small part of a larger, grander design, does not monopolize, or even dominate the design Hester is supposed to see when she looks into the breastplate’s funhouse mirror in Hawthorne’s prose.

<11> In the next chapter’s image, as Hester crouches towards Pearl in the right half of the picture, sunlight streams diagonally toward her, male accusers stand above her, but, interestingly, they do not cast shadows upon her (figure 6). Everything about the image highlights her visibility before the men and before viewers. The men’s gazes and our sight as viewers converge upon a crouching woman who is about to tell Arthur, “Look thou to it!” to make her case (I: 117). Hester’s lover and her husband insinuate themselves into the governor’s audience, effectively rendering themselves invisible during Bellingham’s interrogation. To view them is not to see any evidence of guilt. To pick them out in Foote’s image is not to notice any visual signs of their kinship. To view Hester is to see the emblem of her crime and her crouch of penitence. She is the member of this community marked as Other, fallen, and guilty, morally speaking. Arthur is the one who can skirt the sunbeams that highlight Hester. The image itself cannot quite explain the sunlight’s configuration—light streams upon Hester, somehow shrouds Arthur, and does not leave Arthur casting any shadows—and yet Foote’s fixing of shadows accords with Hester’s hyper-visibility as Pearl’s mother, and Arthur’s invisibility as Pearl’s father.

<12> Three figures appear heart-shaped in the next image, the second of three scaffold scenes (figure 7). Arthur and Hester form rounded curves at the top of the heart, with Pearl as the lowest point. Our sights have risen since the first scaffold scene, to show the illumination of the comet that brings an “A” to the sky the night of the governor’s death. Worn, wider in body, and worse for wear in their elaborate shrouds, Hester and Arthur have guilty, upturned expressions. The scaffold reminds us of earlier picture frames. The stocks’ holes for heads and hands again draw our attention amid the wood’s coarse grains. Pearl gestures toward where she would like the three of them to stand again in the morrow’s full daylight, but neither parent meets her eye. White arms and sleeves cross this heart, as it were, slicing through the darkness of their coats.

<13> If scaffold scenes require Foote to put her characters in public, elevated displays, sylvan scenes demand energetic strokes from Foote’s ink pens as she adorns “The Pastor and His Parishioner,” showing the child at the brook side, and subordinating a penitent Dimmesdale to a towering, comforting Hester (figure 8). Away from the prying eyes of the townspeople, they assume expressive stances of her assurance and his contrition, as, in one image, he submits to her comfort in his grief. As though she is determined not to depict the chapter’s most dramatic moment of action, Foote does not show Hester casting off the letter, nor the “flood of sunshine” intimating that heaven approves of her renunciation. Instead, Foote has a pouting Pearl reflect her mien in the waters, shows a moment after the letter is presumably returned to its place, and has Arthur anxiously watching Pearl’s return. If one ponders the blank canvas with which Foote began this rendering, her elaborate labor to create vegetative undergrowth, the tall grass representing their wild, temporary temptations, Foote’s art seems almost penitential in itself. The artist’s vigorously sustained labor recreates the merely fleeting impression the heroine had ever been free. Foote spends more time shrouding Hester in opaque undergrowth, and having the heroine turn her back to viewers, than Foote ever lends Hester’s “A” additional exposure in the illustrations.

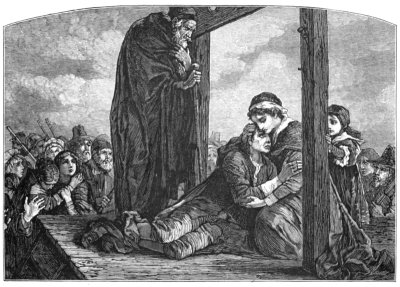

<14> The final scaffold image reconfigures the framing of the stocks as well as the posing of the characters, creating a definite progression rightward, through the gate of the scaffold and towards Pearl, who is posed stage right, as it were, in the scene (figure 9). A solemn Hester on one side of the scaffold receives a recumbent, dying Arthur. He crosses from one life to the next, assumes his final positions, and extends away from Roger (above him), toward Hester, who receives him. She assumes the classic pose of a Pietà, cradling Arthur as Mary, her counterpart, would comfort a recumbent, emaciated Christ. Though Arthur’s final speech in Hawthorne’s prose is more about his own transgressions, curiously constructed as a rhetorical one-upping of Hester’s suffering, he looks appealingly toward Hester in Foote’s picture. Visually, he begs for her forgiveness, though verbally, he speaks more about himself. The crowd’s grief supplants their earlier jeers. Roger, meanwhile, merges visually with the stocks. He appears to be a commemorative overseer for Hester and Arthur to move past or pose beneath, more than he seems to be a fellow human being, with whom they might engage. Foote has removed Roger from this family grouping, coloring him darkly and associating him instead with the punitive structure that has persecuted them. Hester and Arthur seem in the image to have progressed together beyond the obstacle Roger represents, through the gateway the scaffold has come to resemble, and finally into Pearl’s eager, yet eclipsed embrace. The image’s top arc recalls the prison-door shape of earlier scaffold images, even as the scaffold’s upper-most point pokes outside Foote’s image. Obscured by the scaffold’s right support, Pearl looks through it toward her mother, her carriage and posture echoing Hester’s stance. The infant, Christ figure, and comforter, are thus strikingly reconfigured: Foote not only repositions Hester like a virgin, but reimagines her as The Virgin in Christian iconography.(7)

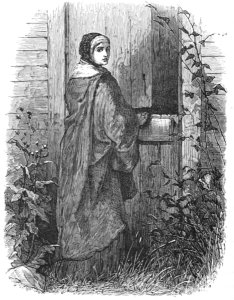

<15> Hester, but not Pearl, appears once more after this scaffold image, meeting our eyes for the first gaze we reciprocate (figure 10). “On the threshold,” she hesitates, “turned partly round, —for, perchance, the idea of entering all alone, and all so changed, the home of so intense a former life, was more dreary and desolate than even she could bear. But her hesitation was only for an instant, though long enough to display a scarlet letter on her breast” (I: 261-2). Foote does not “display” the letter, but she does capture Hester’s hesitations, including the viewer’s gaze in Hester’s reciprocated sights. Foote never asks us to look out of, nor through any of these images, as though we are Hester. That we see the novel’s world through others’ eyes, not through the heroine’s, contributes to her visibility and objectification. That her gaze in this, her last appearance is direct, even challenging, asks us if, after all that has happened, we finally see her, or still only see her letter. Her look finally meets our own, encouraging us not to fixate any further on Hester and her letter but to reflect upon ourselves and our own transgressions.

<16> The letter, of course, forms the final image, as it does with other, earlier editions. “Gules” in heraldic calligraphy on the book’s final page (I: 264), it speaks monosyllabic condemnation from Hester’s shared tombstone, and makes the volume a “red-letter edition.” Hester does not need to “display a scarlet letter on her breast” in her last image, if the novel displays the letter on its last page. Foote does not render the “A” any more than she needs to, minimizing it chastely on Hester’s breast when she does. Foote’s images teach us not to look directly at Hester any more than we need to in turn. We see her as a fellow transgressor and sympathetic, if guilty party, even when, in the novel’s foreground, other viewers sanctimoniously place themselves above her instead. We look within Foote’s The Scarlet Letter’s subtle artistry; we do not solely look at the heroine, set up to be a spectacle in Hawthorne’s art. We see Hester Prynne faithfully redrawn, but we also sense The Scarlet Letter has been reconfigured to inhibit her harshest accusers’ stares.

* * * * * * * * *

<17> Foote’s edition separates prying audiences in Hawthorne’s novel from more respectful, more ethical audiences of Hester’s narrative, as it differentiates between the discreet, interpersonal glances of the seventeenth-century setting, and vision as it is informed by more contemporary graphic arts. Early descriptions of Hester so strongly emphasize her visibility to Hawthorne’s Puritans, one easily misses her obscurity to Hawthorne’s readers. “Hawthorne puts his surrogate audience into the text to guide his own audience’s responses,” writes Stephen Railton; “His readers could watch them watching the story, and learn from them how not to read The Scarlet Letter” (143). In Foote’s images, we watch the Puritans, watching Hester. We look out of the prison house, at a fellow sufferer; we do not look at her as though we are staring, sanctimonious superiors. “The audience,” Railton writes, “forced to abandon any privileged position as mere spectators, must become an active part of Hawthorne’s interpretive community” (149). “Prynne stands before the crowd” within the novel, “not ‘fully revealed,’ as the text claims,” Shari Benstock writes, “but fully concealed, her sexual body hidden by the cultural text that inscripts her” (300). Hawthorne and Foote do not falsely simplify the act of looking, or divorce it from the subjectivity of interpretation. Hester emerges as a subject we respect, precisely because she suffers under others’ disrespectful observation.

<18> Hawthorne’s chapters, privy to Hester’s emotions and the spite of her accusers, distinguish between looking rightly and wrongly, between glancing with respect and staring as a voyeur. “When strangers looked curiously at the scarlet letter,—and none ever failed to do so,” we are told, “they branded it afresh into Hester’s soul; so that, oftentimes, she could scarcely refrain, yet always did refrain, from covering the symbol with her hand. But then, again, an accustomed eye had likewise its own anguish to inflict. Its cool stare of familiarity was intolerable” (Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter I: 85-6). To look is to antagonize, categorize, and implicitly place the viewer in smug, higher regard. When Hester intuits that others might share some of this disdain, she wonders of her hunches: “Could they be other than the insidious whispers of the bad angel, who would fain have persuaded the struggling woman, as yet only half his victim, that the outward guise of purity was but a lie, and that, if truth were everywhere to be shown, a scarlet letter would blaze forth on many a bosom besides Hester Prynne’s?” (I: 86). Others’ stares designate Hester as the guilty party. Her accusers make her take the fall for their own imperfections and fail to disclose their own transgressions in turn. They look at her, in sum, to “slut-shame” Hester Prynne. Foote conceals her letter, gives her respectful distance, and disallows condescension. As Foote’s viewers, we are not equipped with others’ means of accusingly, self-servingly surveying Hester.

<19> Visibility is in fact a gendered quality and a dubious distinction. Men, their marital and paternal status invisible and unmarked, say they envy and venerate a woman whose status is all tooevident. “Heaven hath granted thee an open ignominy,” Arthur says publicly to Hester, contrasting her “open” stigma with others’ unreadable signs, “that thereby thou mayest work out an open triumph over the evil within thee, and the sorrow without” (I: 67). Visibility colludes with male transgressors, who hide their sins and join the accusers; visibility conspires against females, who are openly accused, physiologically marked in pregnancy, forever performing their penitence before unseen accusers. Arthur can persuade Hester to speak publicly about Pearl’s conception, even as his words, his office, and his appearances conceal his own complicity in it. Arthur and Roger can insinuate themselves within Governor Bellingham’s audiences, ensconced in anonymous shadows, even as Hester reflects accusatory sunshine, performs public penitence, proves her worth as a mother, and bears the burden of visibility. Men who have conspired in and accused her of sin do not even cast shadows in Hawthorne’s world, or in Foote’s scenes, which conceal and accommodate males’ transgressions.

<20> Arthur may wish his sins were as legible as Hester’s, but he profits from obscurity. The light and the letter outline Hester’s crimes exclusively. Arthur whispers:

Happy are you, Hester, that wear the scarlet letter openly upon your bosom! Mine burns in secret! Thou little knowest what a relief it is, after the torment of a seven years’ cheat, to look into an eye that recognizes me for what I am! Had I one friend,—or were it my worst enemy!—to whom, when sickened with the praises of all other men, I could daily betake myself, and be known as the vilest of all sinners, methinks my soul might keep itself alive thereby. (I: 192)

He constructs her visibility as her consolation, as if invisibility were the greater torment. “O Hester, what a thought is that,” he says, “that my own features were partly repeated in [Pearl’s] face, and so strikingly that the world might see them!” (I: 206). His progeny might betray him. His daughter might become a script in which others could read paternity, rendering him unable to hide as his co-conspirator.

<21> “With a convulsive motion,” he finally removes all distinctions between Hester’s and his own visibility: he “tore away the ministerial band from before his breast. It was revealed! But it were irreverent to describe that revelation. For an instant, the gaze of the horror-stricken multitude was concentred on the ghastly miracle; while the minister stood, with a flush of triumph in his face, as one who, in the crisis of acutest pain, had won a victory” (I: 255). Foote does not render this “revelation.” She renders Hester comforting Arthur, saves us from having to read the minister’s chest, preserves ambiguities about what appears there, perpetuates Hester as the comforter, and Arthur, as the one receiving comfort. To achieve “the true way to interpret the novel,” Railton determines, “we must not only pick up The Scarlet Letter—we must wear it, must admit the truth it tells us about ourselves” (145). One must bear the stigma of one’s transgressions, feel the weight of accusers’ stares, and realize how much effort it would take to persuade others to read “Angel” or “Able,” and not “Adulteress,” in one’s constant label “A.”

<22> If it is “irreverent” to look upon Hester’s letter or Arthur’s breast, Foote remains discreet. If Foote must recreate Hester as other characters regard her with hostility, Foote can let spaces between illustrations stand as reverent, respectful omissions. If Foote passes over some of Hawthorne’s opportunities to illustrate, her blank spaces become signs one need not always know the letter, as it were, of others’ transgressions. Foote redraws Hester Prynne faithfully in her visual adaptation, but she also reconfigures The Scarlet Letter, literally diminishing the “A”’s proportions and predominance in her images, and figuratively reorienting characters’ and viewers’ imagined perspectives on Hester as an accused transgressor. To read Foote’s Hawthorne is to know one sympathizes most, when one has learned not to scrutinize, but to demur, and to understand that one acts most empathetically toward Hester, in fact, when one just kindly looks away.

<23> The reverence that Walter Benjamin taught us to have for the aura characterizes Hester’s appearances more than the reproduction of photographs or motion-picture cameras can. “Those who had before known her” among the initial crowd of glowering Bostonians, “and had expected to behold her dimmed and obscured by a disastrous cloud, were astonished, and even startled, to perceive how her beauty shone out, and made a halo of the misfortune and ignominy in which she was enveloped (Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter I: 53). An aura glints in this angel’s “halo” and pathos is ethereal. “The point which drew all eyes,” which “transfigured the wearer” was the crimson “A,” such that some viewers, “who had been familiarly acquainted with Hester Prynne, were now impressed as if they beheld her for the first time” (I: 53-4). Her appearance is emphatically not a familiar reiteration, a photographic reproduction. She is, rather, an iconic original, a sight her familiars behold as though they have never glimpsed her before. Though Hester may have become familiar to later generations as a motion-picture character, the book wishes we would almost worshipfully remember her with an angel’s halo, an aura’s preservation. Though we have become accustomed to seeing her reiterated and reinterpreted in various film adaptations, her original story specifically asks us to imagine her as a sight which photographic and cinematic technology cannot match.

<24> Even in Foote’s illustrated edition, viewers must earn their views of Hester Prynne. One intuits what it would feel like to wear a letter, and understands Hester portends, but does not yet embody, social tendencies toward more liberated femininity. One awaits the ends of lengthy prose chapters for a single, withheld illustration, and pictures Foote’s energetic artist’s strokes transforming blank canvasses into images of lush undergrowth. Even as the novel advances a step into the more visual realm of illustrated books, and out of exclusively prose, “red-letter” editions, Foote does not facilitate readers’ thoughtless access to cinematic optics or intrusive surveillance. She supplements picturesque modes and mere visual adornments with deft strategies for hiding and veiling what readers still have no right to see. Visualizing this novel for reading audiences does not mean broadcasting images of Hester for all to behold, but making reader-viewers feel the effects of gendered visions on how one sees, how one stares, and whom one may, and may not, judgmentally look upon.

<25> Project Gutenberg’s digitization, the Victorian Web’s reproductions of illustrations, and the recent reissuing of The Scarlet Letter by an imprint called Timeless Classic Books, with Foote’s illustrations, now colorized, once again restore alternative readers and readings to these reproduced, re-visualized texts. At the physical margins of editions of Hawthorne’s romance dating from the 1870s woman-authored images lend distance and privacy to a heroine whom others in the novel subject to surveillance. At the social margins of industries which were dominated by male authors and publishers, a woman artist, in her own way, edits an author’s imagery from within. Her commissions sketch and reconfigure, even as her omissions reverently screen, a newly empowered, respectfully distanced, even a discreetly revered, Hester Prynne.