<1>During renovations in the late 1990s, a ‘wallpaper sandwich’—made up of twelve preserved layers of wallpaper—was removed from the wall of a student room at Peterhouse College, at the University of Cambridge. This sandwich, now in the collection of the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture at Middlesex University, provides a tangible connection to the temporary domestic spaces created by the students at the college. Unique within the museum’s collections, these wallpapers were chosen, hung, and lived with by generation after generation of students for over two hundred years. The wallpapers salvaged from this discovery were hung between 1795 and the twentieth century. The designs of these papers range from delicate florals to stylised, block-printed designs, and provide a microcosmic view of the tastes of generation upon generation of male Cambridge students.(1)

<2>This study situates the Peterhouse College wallpaper sandwich within discussions of masculinity, craft, and domestic space in the nineteenth century. Jane Hamlett’s study of photographs of student rooms demonstrated how male and female students used domestic interiors to explore their means and methods of material expression (Hamlett 133). Assumptions about the aesthetics of masculine space, and gendered binaries surrounding the production of domestic schemes, have been problematised by Hamlett, as well as Deborah Cohen and Karen Harvey. The multiplicity of domestic masculinities and femininities revealed by Hamlett, Cohen and Harvey has unveiled the complex relationship between interiors and gender. This paper builds upon these discussions, examining the layers of wallpaper through the framework of material culture studies. Approaching domestic masculinity through the very objects that filled these spaces exposes the vast array of tangible, physical, and often ephemeral evidence available. The wallpaper sandwich acts as a material time-capsule, providing a biography of the aesthetics of the room and its inhabitants over nearly two centuries.

<3>Adopting material culture studies as a framework enables a closer examination of the relationship between consumption and craft in the creation of these interior spaces, as well as the relationship between domestic space and selfhood. Dominant codes of masculinity have traditionally placed men as producers, and depreciated male engagement with consumption. The feminisation of consumer culture has manufactured this false binary, and over-simplified the relationship between producer and consumer roles. Close scholarly engagement with material culture has enabled the dismantling of these gendered binaries, and unveiled the impact that engagement with making had on the crafting of gendered material identities. The students who lived and worked surrounded by these wallpapers possessed a great deal of autonomy over the decoration of their rooms, repapering and redecorating as they wished, with very little institutional interference. Able to mimic or defy the aesthetic conventions of their parents’ homes, students were given relative freedom to express themselves aesthetically, and to craft a new and independent identity through their domestic space. Craft offers an excellent vehicle through which to break down the traditional male/female and producer/consumer binaries which have dominated historical and scholarly perceptions of consumption and gender. Although individual objects were not necessarily crafted by hand by either the male or female students, the re-appropriation of their consumer engagement with material culture acted as a means of crafting a sense of self-hood through domestic design. The creation of domestic interiors, much like the commissioning of fashionable garments, took place as an active and creative collaboration. Consumers were not passive, but actively engaged in a series of design choices that gradually fashioned the interior space over time. The private rooms of these students represented a domestic haven within the institutional confines of the nineteenth-century university college: a space where students could begin to craft their individual identities as young men.

<4>Masculinity and domesticity, much like masculinity and consumption, are terms which have traditionally been disassociated. Generally connected to the household and homeliness, domesticity has generally been discussed as synonymous with women, marriage, and children – considerations far from the mind of most nineteenth-century undergraduates (Vickery, 2009 53). The strongly gendered treatment of the design, decoration, and material culture of private domestic space had, to some extent, erased our awareness of masculine experiences of crafting interior spaces. However, the recent work of Harvey, Hamlett, Cohen and others, has revealed these domestic spaces as self-consciously created representations of selfhood, and unveiled the complexity of masculine domestic experience. Far from spurning domestic design as a feminine pursuit, the young men of Cambridge actively engaged with the crafting of their own domestic havens. Within the overtly traditional, manly culture of the university, the diversity of masculinities presented in these spaces is intensified (Ellis 263). While the trope of the lazy, rowdy, and rich university undergraduate prevails, age, generation, sexuality, academic ability, and homosocial groups contributed to a multiplicity of masculinities (Hamlett 157). This identity was expressed socially, through participation in college activities, but it was also crafted through the material culture of college life. Indeed, the two were often closely intertwined. The domestic space provided to new college students in the form of their rooms—usually a bedroom and an adjoining study—was reconfigured into a canvas for the expression of a broad range of complex masculinities.

<5>When the homogenous student trope is interrogated, a complex system of crafted masculinities, and the material means for the expression of these identities, emerges. No longer tied to parents, tutors, or school-masters, young men entering the college were creating a new identity for themselves, both metaphorically and materially, through the decoration and material culture of their rooms. Conceptualising these masculine identities as ‘crafted’ helps us to understand the process of intentional manipulation and piecing together of the components of a personalised material identity, which these young men undertook. Some aspects of a room—such as furniture—were occasionally assimilated by each generation of students. For example, Hamlett’s research has revealed that many young men sold on their furniture to the next occupant (Hamlett 143). However, these inherited objects were integrated into broader, personalised domestic schemes. The overall cohesion of the domestic space was therefore inherently crafted: a bringing together of new and old, institutional and personal, conventional and subversive.

<6>The transitory and impermanent nature of wallpaper meant that it was easy to replace and overwrite the identity articulated by the previous occupants of these college rooms. Using a selection of the papers from the Peterhouse College wallpaper sandwich, held at the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture, as a framework, this article examines the domestic spaces crafted and inhabited by nineteenth-century students. Re-contextualised alongside accounts of college life, literary depictions of student rooms, and photographs taken in other nineteenth-century Cambridge college student rooms, these wallpapers allow us to piece together a new narrative of masculine material expression, in which the increasing affordability of wallpaper in the nineteenth century led students to take a more active role in crafting a domestic haven within the college.

<7>Peterhouse College (fig. 1) is the oldest college at the University of Cambridge, founded in 1284. The list of alumni includes Charles Babbage, the computing pioneer, Henry Cavendish, who discovered hydrogen, and Sir Christopher Cockerell, inventor of the hovercraft, alongside a wealth of politicians, Bishops, and cultural leaders. When the first paper from the wallpaper sandwich was hung, the college had recently passed its five-hundredth year. Students at Peterhouse, as with many of the other historic colleges at medieval universities such as Cambridge, Oxford, and St Andrews, were intensely aware that they were only the most recently young men to occupy these hallowed college rooms (Deslandes 20). In his 1909 history of the University of Oxford, Ralph Durand explicitly wrote that “so long as Oxford’s stately colleges preserve even a semblance of their ancient form, they will have power to bring us in some degree into communion with those who lived and worked, thought and played within their walls” (Durand 2). This sense—both metaphysical and material—of ancient inheritance and institutional identity seeped into the domestic experience of living in the college. The wallpaper sandwich provides an intensely tangible means of accessing these layers of student inheritance.(2) The palimpsest-like nature of the wallpaper allows us to strip back through each superimposed layer of student taste. Through assessing the date, quality, production methods, and stylistic qualities of each layer within the sandwich, we can piece together a century of this heritage of student experience.

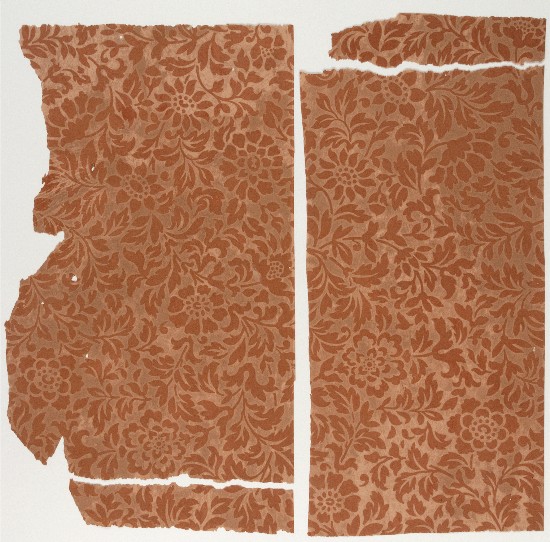

<8>The decision to separate the wallpaper sandwich into its individual layers has allowed the identification of each wallpaper by its printing techniques, paper-manufacturing methods, the quality of the paper used, and its style and aesthetic. The bottom layer of the sandwich (fig. 2) dates from the final years of the eighteenth century. It is a handmade laid paper, of relatively poor quality. Laid paper was constructed by soaking cotton, linen and wool rags to make a pulp, which was laid on wire bottomed moulds measuring about 55cm by 60cm. This was common production practice until the 1840s. The counterpart to laid paper was the higher quality wove paper, which was developed around this time. These wove papers were finer, and were left with no imprint of the wire mesh on the paper, unlike laid papers. The design is block printed in black and white, and the vibrancy of the original yellow ground is still visible on the salvaged piece. The all-over pattern of dark leaves and sprays, small white flowers, and biscuit-coloured base would have been particularly striking before the colours faded.

<9>This fragment of domestic ephemerality is symptomatic of the growing popularity of wallpaper in the eighteenth century, and acts as a prelude to the more active use of wallpaper in the room in the later nineteenth century. The first record of paper used to decorate an interior wall dates from 1509 and was recovered from another of the University of Cambridge’s colleges, Christs College (Vickery, 2009 167). It was not until the eighteenth century, however, that wallpaper came into regular use as an alternative to expensive textile wallcoverings, or the hanging of heavy tapestries (Hoskins; Rosoman; Lipsedge 46–47). During this period, wallpaper was primarily used to decorate private spaces – bedrooms and dressing rooms in particular (Vickery, 2006 201). This early use of wallpaper in the student room marks this space as a sanctum and a domestic refuge within the institutional formality of the wider college, highlighting the equivalency of the student room and the private spaces of the bedroom, dressing room, or closet.

<10>Wallpaper was affordable and ephemeral. Unlike paint, panelling, or bare plaster, wallpaper could be easily and instantly updated. The transient status of wallpaper therefore made it an ideal medium for the crafting and recrafting of multiple masculine identities within the university college. By 1785, more than 2 million yards of paper were consumed each year, and 11 yards of paper were the equivalent cost of only 1 yard of damask (Vickery, 2009 168). Even within permanent homes, consumers of the fashionable middling sort were regularly changing their wallpapers every three to five years (Museum of London, 80.71: ‘Martha Dodson’s account book’). Although Amanda Vickery has argued that the decisions behind the purchase of wallpaper, even by men, were heavily influenced by female relations (Vickery, 2006 205), single men assembling the domestic interior of bachelor lodgings would often seek advice from parents, sisters, manufacturers and peers about their choices (Hussey and Ponsonby 55). Fashionably “neat and not too showey” the paper chosen for the Peterhouse room would nonetheless have been a striking change from the simple plastered walls which surrounded the previous occupants of the room (Vickery, 2006).

<11>Despite the relative ephemerality of wallpaper, and its increased affordability in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, it would take another fifty years for one of the occupants of the student room at Peterhouse to take it upon themselves to repaper the walls. The second paper in the sandwich is a machine printed paper, rather than hand block printed, and is of extremely poor quality (fig. 3). The low quality of this paper is immediately evident, as the coloured blocked are misaligned, and the design has not transferred cleanly the paper. The design features a white ground, with lattice detailing in gold, with a ruddy-brown motif inside each. There are hints of the popular gothic, reminiscent of the Puginesque motifs popular at the time, but this is a poor imitation of a fashionable aesthetic. It is likely that the 50 years of wear and tear endured by the paper beneath had led it to become too dirty and tired for this latest occupant to endure.

<12>The large, fifty-year gap between the hanging of the first and second papers is in accordance with contemporary depictions of student rooms in contemporary literature. The Adventures of Mr Verdant Green: An Oxford Freshman was published in 1853, and contains numerous descriptions of the social and material life of a university undergraduate of the mid-century. The protagonist, when first introduced to his own room, noted that:

The once white-washed walls were coated with the uncleansed dust of the three past terms; and where the plaster had not been chipped off by flying porter-bottles or the heels of Wellington boots, its surface had afforded an irresistible temptation to those imaginative undergraduates who displayed their artistic genius in candle-smoke cartoons of the heads of the University, and other popular and unpopular characters (Bede 30).

<13>This description of a shabby, rough domestic space reflects none of the neatness and politeness assumed of Vickery’s eighteenth-century wallpaper consumers. However, it does depict and intensely masculine material environment, constructed through use, reuse, wear and tear. Masculine domestic comfort in the university college of the 1850s was crafted not through the careful maintenance of a pristine domestic space, but rather through the intentional display of crafted neglect. The decorative statement of this crafted neglect is further demonstrated when the room is repopulated with the broader material culture of the space. The walls, whether covered in ancient wallpaper or student graffiti, provided a backdrop for a complex material culture of student identities. The “stale odours of the Virginian weed that rose from the faded green window-curtains, and from the old Kidderminster carpet that had been charred and burnt into holes with the fag-ends of cigars” in Mr Verdant Green’s new student rooms is intensely material and sensory (Bede 33). Indeed, while the general aesthetic was worn and tired, many students indulged in sometimes excessive consumption of food, prints and drawings, trinkets and ornaments which, small and portable, could be carried on to each new temporary lodging.

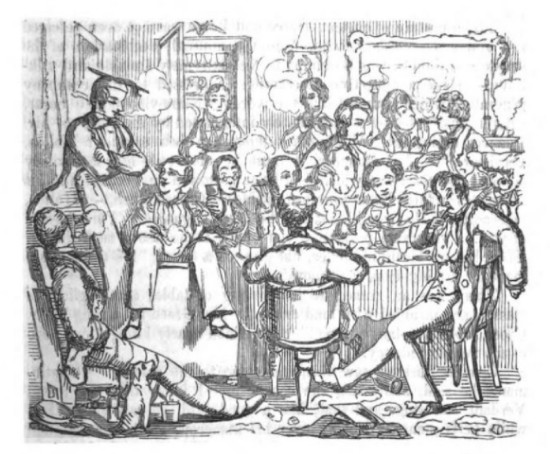

<14>Paul Deslandes has argued that the accumulation of this collection of objects was an important step in crafting adult identities for these young men (Deslandes 66). While many came with items acquired at school or brought from home, ownership – however temporary – of a domestic space of their own in which to articulate and explore an independent identity was relished. Students often acquired a small amount of furniture from the previous tenant of the room. Indeed, for Mr Verdant Green “there was not a superfluity of furniture in the room; and Mr Smalls having conveyed away the luxurious part of it, that which was left had more of the useful that the ornamental character” (Bede 30). In order to fashion a semblance of domestic comfort, male students were avid consumers, often consuming unwanted items from each other (Finn). The illustrations which accompany the tale of Mr Verdant Green conjure up an impression of the richness of this masculine material life (fig. 4). Lamps, glasses, carpet, clothing, chairs, mirrors, artwork, and a “well-garnished” table are drawn together into an eclectic expression of studied masculine disarray (Bede 12). The acquisition of these objects not only reflected taste and character, but also frugality and resourcefulness. Cambridge undergraduate Nugent Bankes recorded how he and he fellow undergraduates would visit second-hand shops scattered through the city, and that he acquired “an armchair, a bookcase, and a writing table, all undeniable bargains, and all capable of being put into good working order after a little judicious exercise of the hinges, drawer-handles, and other component parts” (Nugent-Bankes 18–19). This mismatched paraphernalia of youth was a crafted articulation of multiple influencers upon student identity, and a material expression of the attributes of the independent young man.

<15>From the late 1870s onwards, an intriguing change in attitude towards the crafting of college domestic space seems to have occurred. Within the room in Peterhouse, wallpapers, once a shabby backdrop to an ever-changing material landscape, were changed with a remarkable increase in frequency. The mass production of wallpapers significantly lowered their cost and—even amongst the relatively wealthy students of Cambridge—this economic shift appears to have resulted in a new enthusiasm for decorating the domestic college space. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the frequency with which the wallpaper was replaced rocketed. While there was a fifty-year gap between the first two papers, now the papers are changed every three to five years.

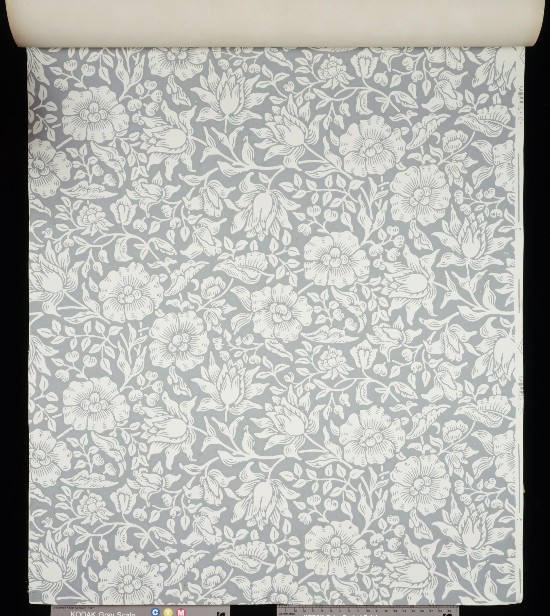

<16>The first layer from within this period of increased frequency of new hangs was placed on the wall around 1879, and was produced by Morris and Co (fig. 5). The choice of this Morris wallpaper demonstrates a more intense interest in fashionable style than was articulated in the earlier wallpaper choices. Similarly, an awareness of, and conformity to, institutional college style is potentially at play. In 1868 to 1874, William Morris, along with Edward Burne-Jones and Ford Madox Brown, were heavily involved in the redevelopment of the public spaces within Peterhouse College, focussing on the Hall and Combination Room (Harvey and Press 76; Kersting and Watkin). The decorative scheme carried out in these public rooms within the college had a strong medieval character, constructed through a mixture of Morris tiles and stained glass, accompanying wood panelling (Banham and Harris 41). Wallpaper was not used in these spaces.

<17>The associations between Victorian masculinity, medievalism, and the Arts and Crafts movement are complex (Ward; Trowbridge and Shattock; Kimmel et al.). Drawing upon a shared academic and literary language and understanding, students would have been familiar with the connotations of the new design of the college spaces (Pugh and Weisl). Whether it was the connotations or the aesthetics of the style which drew him to make this choice is unknown, but this style does appear to have appealed to at least one student of Peterhouse in the 1870s. Although the archival evidence no longer exists to substantiate the idea, it seems likely that the choice was connected to Morris’ involvement with the decoration of Peterhouse, and demonstrates a considered and deliberate association between the contemporary fashion for Arts and Crafts, and the taste of the student occupant. The wallpaper chosen was called ‘Mallow’, and was designed by Kate Faulkner, one of the female designers at Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., and sister of founding partner Charles Faulkner. Contemporary sample books do not explicitly identify Kate Faulkner as the designer of this paper, so it is difficult to ascertain how aware the student-consumer would have been of this feminine connection (V&A, E.811-1915: Pattern book of Morris & Co). This incongruence between a female-designed paper, the masculine Morris brand, and the masculine world of the college, emphasises the fluidity of masculine identity in this period. As Heather Ellis has argued, there were multiple distinctions besides gender which young men drew upon when formulating material and aesthetic identities (Ellis 267). The choice of Mallow—a wallpaper which, for the designer-literate, held an implicitly feminine association—would not necessarily have conjured up effeminate connotations. Jane Hamlett has argued that “neither female nor male students’ décor followed contemporary gendered prescriptions” (Hamlett 138). Indeed, a multiplicity of potential associations could have been read into this wallpaper choice, from socialism to homosexuality, or an anti-industrialist reaction to the machine printed paper underneath (Hamlett 157).

<18>Mallow itself was a popular wallpaper, and more intact samples survive in other collections, as seen in Morris & Co. sample books of the period (fig. 6). In line with the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement, the wallpaper is woodblock, rather than machine printed. Mallow was a mid-range paper, costing around 20 shillings per roll in 1890 (Harvey and Press 174). Its busy aesthetic is a sharp contrast to the pale, soft, and relatively simple styles hung on the walls during the proceeding eighty years. This busy, quintessentially Victorian aesthetic continued through the remainder of the nineteenth-century papers, and indicates a sense of conformity and conservativism in the domestic identity crafted by these students.

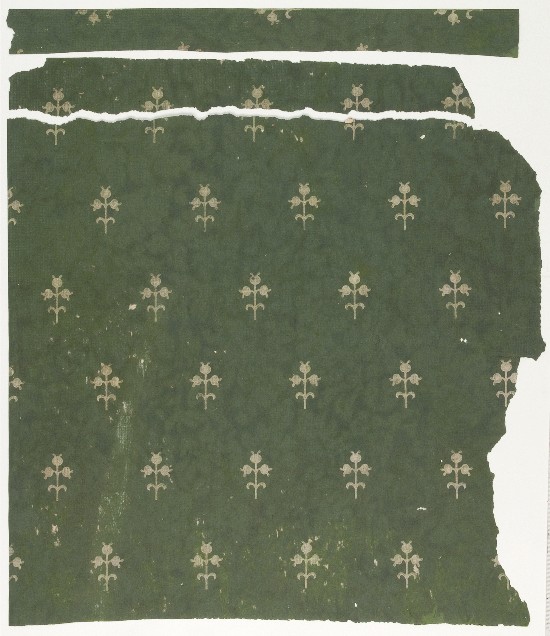

<19>Perhaps the multiple connotations of the Morris & Co. Mallow paper—however they were interpreted by contemporary students—were too incendiary for the students who inherited this room. Indeed, at University College the institutionally-imposed redecoration with Morris wallpaper was swiftly met with rebellion, and students who objected to the designs quickly covered them up (Hamlett 143). In less than a decade, two more layers of wallpaper had been added. The fifth layer in the sandwich is another good quality paper, with a similar floral aesthetic, though without the attribution to a specific designer or manufacturer (fig. 7).

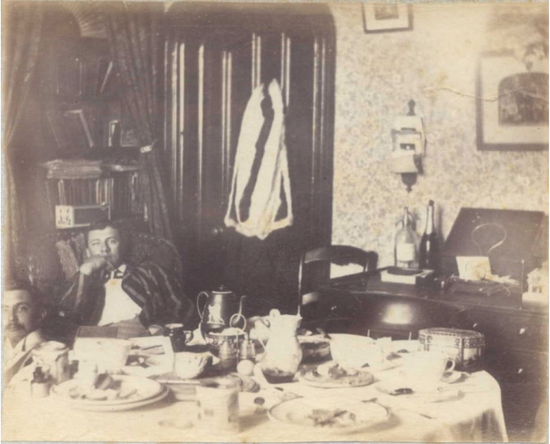

<20>Such wallpapers appear frequently as a backdrop in photographs of college rooms from 1870s onwards. The photographic records of the colleges of the University of Cambridge shed light on the broader material culture existing around these wallpapers. Although photography raises methodological issues as a historical source, Jane Hamlett has demonstrated that it can provide a uniquely insightful source for understanding the everyday material life of students in this period (Hamlett 138). Hamlett’s own systematic study of the female-occupied rooms of Royal Holloway in the late nineteenth century provides a precedent for this integration of photographic sources, though an inherent awareness of the composition of such images is essential (Carter). Just as a painting or any other visual source is self-consciously constructed, so too are photographs. However, without the relevant context as to why and by whom photographs have been taken, unpicking their genre and situating them within broader narratives is complicated. Indeed, as Hamlett discovered within the Royal Holloway archives, the photographical archives of the University of Cambridge are similarly complicated by the anonymity of both photograph and, in many cases, occupant of the rooms photographed.

<21>Sadly, no photographs of student rooms from Peterhouse have been collected in the college archive, but other colleges, and in particular St John’s, have considerable photographic records of the domestic spaces crafted and inhabited by their students. These photographs do not appear to have been the result of a systematic project (like Miss Catherine Frost’s photographs of Royal Holloway, studied in Hamlett’s work) but rather appear to show the students themselves recording their college life. These records of domestic space are undoubtedly arranged and manipulated: crafted and composed representations of self-hood as articulated through students’ rooms and material possessions.

<22>These images place the wallpapers into their social context, as backdrops to a complex material college life. Two photographs of rooms A8 and E6 in New Court at St John’s College (Fig. 8 & 9) depict two wallpapers very similar to the 1890 paper in the Peterhouse wallpaper sandwich. In the photograph of A8, taken in 1889, champagne bottles, books, the remnants of a meal and dark mahogany furniture provide the set dressing for the scenery of the wallpaper. However, these images also betray an affiliation with a new material culture: that of the institution itself. The ‘corporate’ identity of the college, as well as the material evidence of membership within various clubs, societies, and sports teams, is spread across the meticulously composed photograph of room E6, also in New Court, taken in 1898. Membership of such homosocial student groups was an important element of college life (Dougill 97; Deslandes 62). The display of this membership, and the articulation of it as part of student material self-identity, is very much at the forefront of this photograph. However, while these photographs dominate the carefully curated display, photographs of men and women – presumably friends and family members – as well as trinkets, landscapes, letters, cards and invitations, also adorn the mantel piece. Despite the initial impression of a chaotic, male-dominated den, the influence of home, and of familiar domestic life was expressed. Portraits of family members and souvenirs from home acted as elements of a complex new student identity, the meanings and sentiments behind which doubtless evolved as students discovered their new, independent and adult identities (Hamlett 145). The cluttered impression that is created by this informal accumulation of personal paraphernalia is perhaps deceptive. The arrangement of these objects has been carefully crafted and composed, symmetrically framing the fireplace. This material crafting of selfhood is not the careless amassment of ephemera, but a systematic crafting of a complex and multi-faceted student identity.

<23>Continuing the trend of frequent replacement and repapering of the walls of the Peterhouse room, and sixth layer of the sandwich was hung around 1905 (fig. 10), and the seventh at some point between 1905 and 1910 (fig. 11). These are poorer quality papers than that papers those which had proceeded them, and machine printed. Although we cannot be sure of exact dates, the last of these papers was probably not replaced until after the first world war had ended, and possibly not until as last as the 1920s. These papers mark the end of this flurry of wallpaper popularity amongst the students of Peterhouse, with only three more papers being hung between 1920 and the 1970s.

<24>A more formal photograph of an unidentified room, also in New Court, St John’s College, contextualises these early twentieth-century papers. A similar coalescence of personal, college, and family identities is evident, but the influence of popular culture is heightened. Over the mantel—still the focal point for the accumulation and display of smaller cards, photographs and ephemera—the family photographs and mementos are interspersed with caricatures and cartoons. Three posters - for the Gay Parisienne, A Country Girl, and The Geisha are also displayed prominently, although unframed. A copy of the poster for The Geisha, displayed above the door, is also held in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (fig. 13). This was a musical comedy, which opened in London in 1896 and continued to be popular until the 1930s (Richards 266). Interest in theatrical pursuits, and the access they provided to their female performers, was viewed by moralist as highly dangerous for the young men of Oxford and Cambridge (Deslandes 66). However, theatre and music hall productions were enduringly popular, and many undergraduate periodicals contained “theatre notes”.

<25>The sexual undertones of student indulgence in the theatre seems strikingly at odds with the formally crafted composition of these dinner companions, especially as one of the guests was a woman. Women were occasionally guests within college rooms, and often visited the universities to participate in events, such as the boat race, Commemoration, or Commencement (Deslandes 168). Visits from female family members also provided students with an opportunity to practice their more formal, social hosting skills. The presence of these female sisters, cousins, aunts, and mothers to some extent had very little impact on the materiality of the male student’s domestic space. Indeed, emblems of masculinity, such as the clumsy attempt at hanging crossed swords, hang feebly behind the female guest in the photograph from New Court.

<26>The wallpapers which were hung behind these adornments play a crucial role in structuring and crafting the aesthetic of the domestic space inhabited by undergraduate students at Oxford and Cambridge in the nineteenth century. When the wallpapers of the Peterhouse College wallpaper sandwich are contextualised within the broader, highly gendered material culture of the college room, they simultaneously jar against and set-off the youthful collecting and display practices of these young men. Floral wallpapers and cricket bats, ordered motifs, and lopsided fencing swords all sit side-by-side in these temporary domestic spaces, as these boys of the elite learnt how to be men.

<27>Significantly, gender as a binary framework does not seem to have dictated the domestic choices of these men. Instead, thoughtful aesthetic reflection, homosocial cultures, and popular interests and associations seem to have dominated the plurality of masculinities evident in these spaces. The importance of wallpaper as the backdrop for this youthful exploration of the selfhood increased as wallpaper itself became cheaper and more disposable. The resultant transitory, impermanent attitude to domestic design articulated in the wallpaper sandwich highlights that these layers of wallpaper were conceived as temporary aesthetic experiments, allowing students to define their own domestic experience, and that the students who inhabited these rooms crafted their own individual selfhood and masculinity within these spaces.