An interesting glimpse into Mrs. Oscar Wilde’s tastes and surroundings is afforded by a glance through her autograph-book, a plain little volume cased in a charming book-cover made by herself. From the dedicatory verses on the first page, written by the author of “Salomé” to his wife: --

“I can write no stately proem,

As a prelude to my lay;

From a poet to a poem,

That is all I say.”

to the last of the many characteristic utterances contained therein, every signature gives food for thought, and, oftener than not, reveals something of the writer.

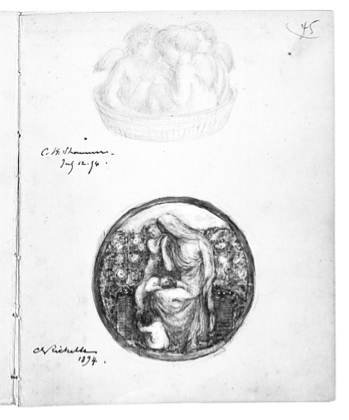

<1>In the twilight of the Victorian period, fashionable society gathered twice a month at 16 Tite Street to attend Constance Wilde’s lavish “at homes.” Only the rich and famous would have received invitations, but that did not necessarily mean guests were prepared for what Anna Comtesse de Brémont described as “the crush of fashionable folk that overcrowded the charming rooms of the unpretentious house in Tite Street” (87). In her stunning biography of Constance, Franny Moyle explains, “Constance treated her… ‘at homes’ as a theatrical exercise where scenery and costume were meticulously planned” (126).(2) As was custom, Constance kept a record of famous visitors to 16 Tite Street and asked many of them to sign her album. Offered a single blank page, some visitors chose merely to sign and date their name as Oliver Wendell Holmes did on the first page,(3) followed by a location and date marker: “London, June 3rd 1886.” Others chose to transcribe extracts from their own published works: Frances Hodgson Burnett inscribed a passage from her most recent publication, Little Lord Fauntleroy (27); George Meredith transcribed a verse from The Sage Enamoured, “Love is winged for two” (36); and Swinburne contributed his poem, “Children” (16). Meanwhile, the artists Shannon and Ricketts added small sketches (45). These entries suggest that writing in Constance’s album offered contributors a venue to advertise their craft. Choosing any of these options might have seemed preferable to the alternative: penning original verse for a lady’s album. Yet these are the most fascinating entries. Faced with a blank page, what did Walter Crane, Vernon Lee, or Mary Elizabeth Braddon decide to write? In this essay, I read Constance’s album as an extension of the social performance staged within 16 Tite Street. The album records writing that plays with the established tradition of album verse at the same time that authors personalized entries with their own style.

<2>Writing in an album such as Constance’s was nothing if not a performance — a highly manicured representation of a public self in a more private setting. Given a page, each contributor made it his or her own. For this reason, the album provides an illuminating view into fin-de-siècle life that paralleled its literary and artistic production. The verse, often epigrammatic, conveys a set of quintessentially decadent themes: sentimentality tinged with anxiety, an enduring concern with beauty heightened by death’s shadow, and frivolity that obscures authenticity. The goals of this article are twofold – I analyze how Constance’s album fits into the nineteenth-century culture of “verse written for a lady’s album,” and I argue that many signatories, conscious of how the tradition had been positioned as an emblem of female domesticity, used their entries to challenge the period’s gendered and sexual norms.

“An Album is a Garden”

<3>Scholarly interest in the materiality and poetics of female sociality, particularly as they forge an alternative to capitalist modes of exchange, has generated a growing fascination with the album tradition. Samantha Matthews, with incisive readings of fictional representations of album culture, has argued that these manuscripts “functioned as a symbolic stand-in for the feminine body” (108). The feminization of albums brought with it a general assessment of the tradition as trivial; however, this “is precisely what makes it suitable to encode unregulated and unspeakable feelings and thoughts” (109). Like Matthews, Patrizia Di Bello emphasizes the tactile quality of albums as material objects that “played an important role in the construction of the genteel identity of women and their families” (3). In other words, the so-called “Lady’s Album” functioned as a way to order and represent social networks that accrued a non-capitalistic value. Di Bello explains that an album “demonstrates her [the lady’s] ability to socialize in a world at once fashionable and learned, using her networking skills rather than her purchasing power to accumulate a small but perfectly formed collection” (50). As Matthews and Di Bello point out, the Lady’s Album tradition developed alongside its commercialized instantiation – literary annuals, which were anthologies of verse and light prose marketed as gifts for the Christmas season. While extremely lucrative for the celebrated authors who wrote for them (Kathryn Ledbetter reports that Walter Scott earned £500 for his contributions to just one edition), they also modelled “alternative economic practices,” to borrow Jill Rappaport’s words. “Annuals not only shaped the way women imagined giving by modeling scenes and styles of exchange but, by cultivating a larger ethos of generosity for this publishing enterprise, also positioned readers as gift recipients, placing them under the burdens and benefits of gift exchange. As gifts, annuals created a reading community” (Rappaport 20). With a pervasive expectation that family, friends, and acquaintances might be asked for a page of verse, literary annuals printed samples of “Lines Written in a Lady’s Album” that modeled conventional sociality.

<4>By the time Constance began to circulate her album in the summer of 1886, the tradition had endured centuries of criticism and praise. In the early-modern period, the album amicorum tradition belonged to men conversant in Latin. As June Schlueter explains in her study of this tradition in “Shakespeare’s London,”

Typically, a contributor to an early modern album amicorum wrote a motto or moral, often in Latin, that served as advice to the album owner and identified the writer as one who was conversant with a classical or contemporary body of wisdom…. Beneath the motto, he wrote a dedication, naming the album owner and honouring him with words of respect or commendation. Usually, he placed his signature at the bottom right, and usually, though not always, he dated and sited the entry. (9)

As an early example of social-networking technology, the album amicorum represented an idealized version of a person’s social circle, filled with famous authors and well-educated thinkers. In the sixteenth century, Melanchthon, describing the German stammbuch, explained, “These little books certainly have their uses: above all they remind the owners of people” (qtd. in Nickson 9-10). Schlueter’s study of the British Library’s collection of early modern album amicorum reveals “[n]ot only did the album owner receive the praise of his contributors with satisfaction; so also was he pleased to have subsequent contributors read what earlier ones had written” (27). While this particular description could equally apply to nineteenth-century albums, two significant shifts in the tradition had occurred. First, by the nineteenth century, the tradition had become almost entirely female and, second, signatories wrote entries in the vernacular. From the early-modern, Latin album amicorum (album of friends) to the “lady’s album,” the tradition had shed its previous scholastic ambitions in favor of feminized domesticity. The lady’s album occupied a central role in the Victorian upper- and middle-class parlor. Among all the other objects on display, Thad Logan explains that “the album was the most popular and the most sentimentally charged” (124). The tradition fits the semi-public, semi-private nature of the parlor and helped to convey the often-conflicting aims of intimacy and distance that Logan claims defined the space. Given the album’s centrality, the nineteenth century produced a great deal of album verse. Indeed, as Michael C. Cohen succinctly put it, “the vast majority of poems written in the nineteenth century were never published” (68). Manuscript albums hold a bounty of relatively unknown and unstudied verse written by both famous authors and common readers.

<5>Positioned as a symbol of female sociality, the nineteenth-century album was increasingly mocked as a trivial pastime. Even Charles Lamb, who published an entire book called Album Verses with a few Others in 1830, referred to them as “trifles” in his dedication. Later, he would defend this publication: “But if to write in Albums be a sin, Lord help Wordsworth — Coleridge — Southey — Sir Walter himself — who have not been always able to resist the solicitations of the fair owners of these modern nuisances” (Miscellaneous Prose 340). All the best poets of the time succumbed to write album verse, so “where was the harm” in teaching others “how they might be best, and most characteristically written” (341)? The very first poem in Lamb’s collection touches on the dominant themes of album-verse in the early nineteenth century: consciousness over the materiality of the album, a reflection on the tradition itself, humility on the part of scribe, praise for the album’s owner, and hints at a future when the writer would be gone but his or her verse would remain.

An Album is a Garden, not for show

Planted, but use; where wholesome herbs should grow.

A Cabinet of curious porcelain, where

No fancy enters, but what’s rich or rare.

A Chapel, where mere ornamental things

Are pure as crowns of saints, or angels’ wings.

A List of living friends; a holier Room

For names of some since mouldering in the tomb,

Whose blooming memories life’s cold laws survive;

And, dead elsewhere, they here yet speak, and live.

Such, and so tender, should an Album be;

And, Lady, such I wish this book to thee. (Album Verse 1-2)

In this sonnet Lamb explains that the album is a kind of collection of people, a bouquet of sorts, filled with the flowers of poesy. He captures the tradition’s unique tenor in the Romantic period: earnest goodness underscored by a macabre shadow of death and, ultimately, transcendence through the vehicle of album verse. Though a friend’s body might be “moldering in a tomb” (8), album verse was viewed as a technology that allowed him or her to once again “speak… and live” (10). Indeed, the 1894 article, “Mrs. Oscar Wilde at Home” (quoted in the epigraph), suggests as much with its description of Constance’s album, claiming that “the simple signatures of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sergeant, the American painter, John Ruskin, Henry Irving, Miss Ellen Terry, and many other familiar and unfamiliar names evokes a vision of what should be a unique gathering of notable men and women”(91). Through the medium of the album, the conviviality of Constance’s “at homes” emerges, though all its participants have long been dead. Despite its impressive ability to (textually) resurrect the departed, Constance’s album is a small, unpretentious thing, but it offers a remarkable imprint of the elaborate social performance staged in the Wilde’s home.

<6>While scholars interested in Oscar (and more recently, Constance) have briefly described the album,(4) it has not received the critical attention necessary to understand the complex and often obscured uses of any nineteenth-century album. The personas that emerge throughout the album are simultaneously revealed and hidden as contributors sign their names underneath what amounts to a public performance rendered in verse. The very idea that identity could be a kind of performance was, of course, woven into the fabric of late nineteenth-century aestheticism. And nowhere was it expressed quite as powerfully as it was in the Wilde household. Constance and Oscar Wilde sat at the vanguard of new expressions of gender and sexuality – most explicitly expressed in The Woman’s World, to which Constance contributed several articles on fashion.(5) Constance’s album offers a glimpse into the more private workings of this important fin-de-siècle community. Each entry marks a personal connection while at the same time denying access to a more private self. The following sections analyze entries in Constance’s album as negotiations of gender and sexuality in relation to the larger tradition of album verse.

“Albumenous Poetry”

“I am ill at these numbers.” Pray tear out the above, if you think proper.

– William Hazlitt, writing in Isabella Towers’s album (8)

In Tite Street I had the privilege of meeting Mrs. Oscar, who asked me to write something in an album. I have always hated albumenous poetry.

– Edgar Saltus

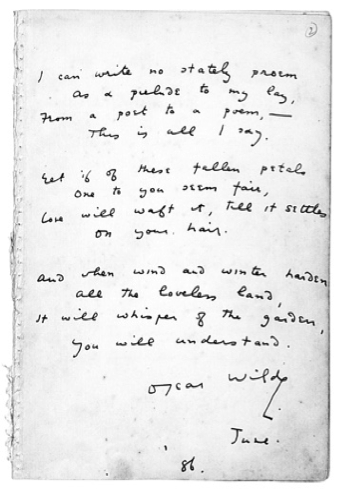

<7>Like Hazlitt and Saltus, contributors often struggled to pen verse for a lady’s album. For some, this struggle became the subject of their entry, as it did with Oscar, who wrote the first full entry in his wife’s album in June 1886. He begins with a refusal and proceeds with evasive claims of love, admiration, and attachment.

I can write no stately proem

As a prelude to my lay,

From a poet to a poem, –

This is all I say.

Yet if of these fallen petals

One to you seems fair,

Love will waft it, till it settles

On your hair.

And when wind and winter harden

all the loveless land,

It will whisper of the garden,

You will understand.

Oscar Wilde

June

‘86

© British Library Board (Add MS 81755, p. 2)

Oscar offers a guarded and often intractable presentation of his relationship with Constance. One reason for this is that Oscar (and the album’s other contributors) could never be sure who would read his entry. As a semi-public genre, lady’s albums forced contributors to make complex decisions about how to represent themselves. While it seemed clear to To-Day that Oscar was the poet and Constance, the poem, one reaches this conclusion because of the line’s placement within the latter’s album. In another woman’s album, it could easily refer to someone else. Written two years after their marriage, Oscar’s contribution to his wife’s album would not be printed until 1893, when Oscar published this poem under the title “To My Wife: With a Copy of My Poems.” Its original (untitled) placement in the album obscures gender entirely. Without the title, the speaker of this poem emerges as an aesthete androgyne – devoid of gender – who expresses an ambivalent sentimentality. Though the speaker conveys tenderness and affection, the verse circles an illegible secret and projects a moment in the future when the lover — the “you” of the poem — might grasp its meaning. While the poem’s published title settles the discourse into a heteronormative relationship, the speaker and the object remain undefined in the album. Oscar begins the poem with disavowal, “I can write no stately proem as a prelude to my lay” (1). This moment of negation is both reversed and re-enforced with the lines that follow, “From a poet to a poem, — / this is all I say” (2-4). The speaker is able to pen something, we learn, but it has already been trivialized (“this is all I say”).

<8>The final two stanzas of the poem continue to withhold and, at times, obfuscate the speaker’s message. The second stanza pivots with its first word (“yet”), followed by a conditional that the speaker can only express obliquely.

Yet if of these fallen petals

One to you seems fair,

Love will waft it, till it settles

On your hair (5-8)

This riddle’s sentimentalism hinges on Love personified and imbued with the power to move “these fallen petals” onto the recipient’s androgynous hair. As Charles Lamb’s reference to the album as “a garden” suggests, the flower had been a symbol for collections of poetry that came to be associated with the lady’s album, by way of medieval florilegia.(6) Following in this tradition, Oscar’s “fallen petals” alludes to his verse and, in keeping with his poem’s modest start, offers these poetic fragments to his wife without presuming she will appreciate them. The conditional construction of this second stanza, maintains an ambiguity that only Constance (if she is, in fact, the poem’s “you”) can resolve. Considering its guarded sentimentalism, this poem cannot but end with secrecy. Oscar’s final stanza imagines a time in the wintry future when the ground will “whisper of the garden.” The final apostrophic line, “you will understand,” conveys a secret that, presumably, the poem’s “you” knows — that “the whisper of the garden” means something. What if, however, the whisper means absolutely nothing? What if this line is nothing more than evasive, and much as the speaker cannot write “a stately proem,” he (or she) also cannot express his (or her) love without deferring to a future self. Speaking in the future conditional, Oscar imagines a fantasy of mutual understanding, forever delayed. At the same time, we only assume that Constance is the poem’s “you” because of its placement in her album. Apostrophe, then, is essentially unstable because it shifts according to context.

<9>In the theater of the late Victorian friendship album, apostrophe serves as a powerful mode of sentimentalism veiled in secrecy. The great rhetorical mode of secrecy, apostrophe, fits the poem’s insistent evasiveness. Moreover, apostrophe is a genderless form. As Barbara Johnson has explained, apostrophe is “both direct and indirect: based etymologically on the notion of turning aside, of digressing from straight speech, it manipulates the I/thou structure of direct address in an indirect, fictionalized way…Apostrophe is a form of ventriloquism through which the speaker throws voice, life, and human form into the addressee, turning its silence into mute responsiveness”(185). Oscar’s poem sets up a fictionalized future that will unravel the verse’s cryptic message. Derrida, in his meditation on friendship, suggests that apostrophes subsume a potentially infinite field of referents. He asks: “What happens when one quotes an apostrophe?” (5). Rhetorically the apostrophic utterance assumes a silence, a distance. There is something unspeakable at the heart of Wilde’s poem, and, similarly, at the heart of the album. In this context, apostrophe bears the force of the epigram, as Amanda Anderson describes its function in Oscar’s work. It “seems always to pull away from the text, and from the context of the action, announcing itself as quotable, transferable, and indifferent….” (148). Album verse is kin to the epigram, both of which are extractable and endlessly portable – for that reason, they both cultivate distance and the ambivalent sentimentality at the center of Oscar’s poem to Constance.

<10>Wilde’s poem is all the more remarkable when considered alongside other nineteenth-century album entries that overflow with explicitly gendered speakers and confessions of love. Consider, for example, the verse Charles Dickens wrote in the album of his young love, Maria Beadnell:

My life may chequered be with scenes of misery and pain,

And’t may be my fate to struggle with adversity in vain:

Regardless of misfortunes tho’ howe’er bitter they may be,

I shall always have one retrospect, a hallowed one to me,

And it will be of that happy time when first I gazed on thee.

Blighted hopes, and prospects drear, for me will lose their sting,

Endless troubles shall harm not me, when fancy on the wing

A lapse of years shall travel o’er, and again before me cast

Dreams of happy fleeting moments then for ever past:

Not any worldly pleasure has such magic charms for me

E’en now, as those short moments spent in company with thee;

Life has no charms, no happiness, no pleasures, now for me

Like those I feel, when ’tis my lot Maria, to gaze on thee.

The acrostic stands in contrast to apostrophe. Here Dickens quite clearly names the object of his affection with the first letter of each line, which, when read vertically, spells out his subject’s name. As if to seal the poem, he explicitly names Maria in the final line. This association between the album and courtship plays out again and again in nineteenth-century literature. One need only think of Elton’s contribution to Harriet’s album in Emma, to understand why the bachelor in W.H. Harrison’s contribution to The Keepsake of 1845 considered albums “a well-disguised species of man-trap, and never saw one opened before him without a shudder, well knowing that a sonnet may be twisted into a promise of marriage” (20).

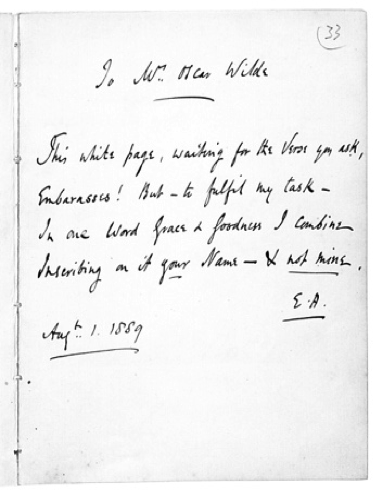

<11>Only two of the album’s contributors mention Constance by name, making most entries transferable and impersonal. When one of these contributors does include Constance’s name, for example, she does so at the expense of her own:

This white page, waiting for the verse you ask,

Embarasses! But – to fulfill my task –

In one word grace and goodness I combine

Inscribing on it your Name – & not mine.

E.A.

Augt..1. 1889

© British Library Board (Add MS 81755, p. 33)

The conceit of this page is, of course, that E.A. signs not her name, but “Mrs. Oscar Wilde” and, in doing so, writes her verse while complimenting the album’s owner. E.A.’s verse plays on several more themes commonly associated with album verse. With her melodic couplets, E.A. echoes a common complaint of facing an album’s “white page” with nothing to write. (The word “album” comes from the Latin albus, which means white.) Additionally, she foregrounds the symbolic power of a signature to communicate virtues such as “grace and goodness,” another common theme in the album tradition. Though the most directly affectionate page in the entire book, its author embedded her sentimentality in anonymity. This is perhaps because the author was probably not a celebrity, but Constance’s aunt, Ellen Atkinson.

<12>From Oscar’s entry onwards, Constance’s album reads as an exercise in the hidden, the unspeakable; surprisingly, the opaquer an entry, the more intimacy it seems to hide. Sharon Marcus has taught us that this is actually typical of Victorian life writing. “Reticence was paradoxically characteristic of Victorian life writing which was as defined by the drive to conceal life stories as it was indicative of a compulsion to transmit them” (34). Laura Zebuhr offers another possible reason: the album tradition set up an impossible problem for those wishing to express genuine affection, as contributors often turn “to an explicitly literary use of language in order to render what is unsayable precisely because one could always say more” (449). Most signatories penned vague verses laden with multiple anxieties. In addition to worrying over appropriate expressions of friendship, many of Constance’s contributors negotiate a more existential concern as they acknowledge how their handwriting will remain while their bodies will not.

“This Hallowed Shrine”

I ask not for the meed of fame,

The wreath above my rest to twine, --

Enough for me to leave my name

Within this hallowed shrine; --

To think that, o’er those lines, thine eye

May wander in some future year,

And Memory breathe a passing sigh

For him who traced them here.

– John Malcolm Esq. (193)

Close as this lock of Hair the ribband binds

May friendship’s sacred bonds unite our minds

– Eliza Cooke’s entry in Anne Wagner’s Album

<13>Malcolm’s and Cooke’s verses both express a hope that writing will embalm their presence. Both entries are clearly gendered. Malcolm, with the pronoun “him,” and Cooke’s with the referenced ribbon and hair attached to the page. It is not uncommon to find a lock of hair in an album – such as the braid Cooke includes with her entry – because the album page was itself a metonymic representation of the signatory’s body. Given the album’s traditional focus on memory, its very existence became a monument of sorts, a “portable graveyard,” to borrow a term from an 1820s journal article (Beinek 1). This morbid tone serves as another theme. For example, consider an album from the 1850s kept by a young woman named Lizzie. Every friend who penned an entry also signed his or her name on the album’s first page. Years later, Lizzie would go back to their signatures and record the date each of them died. Her friend, Sally Beesley – whose signature is followed by the following note - Died Feb 9, 1864 – explicitly asked to be remembered in the album after her death by quoting John Malcolm’s poem “I ask not for the meed of fame,” changing the pronoun to the feminine and signing her name on January 15th 1858. Beesley had already imagined her friend’s album as a mausoleum and asked that it be a place for her remembrance.

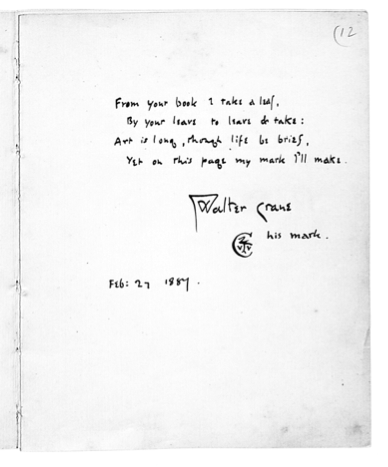

<14>Similarly, Walter Crane imagines a time when his writing exists but his body does not. His entry attempts to tame the abyss by constructing a space in the album that simultaneously signifies life and death. Extending from the maxim, “art is long, though life be brief,” Crane inscribes his signatory mark, which appears on his published works. Punning on the homophone “leaf” and “leave,” Crane claims this page as his.

From your book I take a leaf,

By your leave to leave or take:

Art is long, though, life be brief,

Yet on this page my mark I’ll make.

Walter Crane

His mark

Feb: 27 1887

© British Library Board (Add MS 81755, p. 12)

Not only does he emphasize the very thingness of the paper – the leaf – he also turns his writing into a concrete object, an anchoring presence in the face of oblivion. The page becomes a poor proxy for the body. Crane knew his mark would outlast his own existence. The moment of composition quickly dissipates once Crane pens his mark and dates the page. His self-reflective inscriptions reinforce the album’s physicality, which, as Crane points out, stands in contrast to the body’s frailty. Crane stands in uneasy relation to his own mortality and his entry presents a generalizable body made specific only with his signature. His mark functions as a second signature, another symbol of his embodied presence. However, by labelling it “his mark,” Crane accomplishes two contradictory things. He genders the page; however, in doing so, he also detaches himself from the markings left by his hand. The symbol is no longer “my mark,” as it was in the final line of the verse, but rather, “his mark.” In other words, Crane marks his gender at the same time that he distances himself from it.

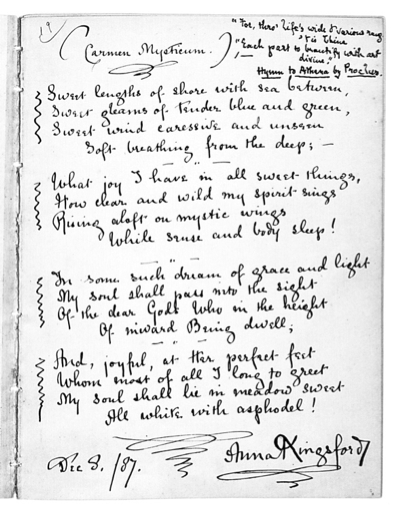

<15>The album provided a space for signatories to meditate on death and immortality, the division of soul and body, and “the power of writing to bridge these two realms” (Beinek 37). As such, it was a space primed for mystics like Anna Kingsford.(7) She provides another consideration of death as a separation of spirit and body. However, unlike Crane’s playful rhymes, Kingsford’s poem strikes a solemn tone as it depicts a peaceful afterlife in elysian fields. Kingsford claimed to receive visions in her dreams, which she would immediately record in her diary. One of these was the “Carmen Mysticum” that she inscribed in the Wilde album. As one of the first women to earn a medical degree, Kingsford was not one to acquiesce to societal expectations. She soon became a leader in Victorian occultism. In fact, it was Kingsford who brought Constance Wilde into the folds of the Theosophical Society, which attempted to use science to explore psychic powers. As Alex Owen explains occultism provided a reprieve from gendered assumptions: “For women, the occult presented an opportunity to develop a masculine persona that in a quite different context was being pilloried by critics of the ‘manly’ woman” (88). Kingsford’s vision is genderless until the end, when the speaker encounters a female god – Athena: “And joyful, at her perfect feet / Whom most of all I long to greet” (13-14).

“For this life’s wide & various range

‘tis thine

“Each part to beautify with arts

divine.”

Hymn to Athena by Proclus

(Carmen Mysicum)

Sweet lengths of shore with sea between,

Sweet gleams of tender blue and green,

Sweet wind caressive and unseen

Soft breathing from the deep; –

–“–

What joy I have in all sweet things,

How clear and wild my spirit sings

Rising aloft on mystic wings

While sense and body sleep!

–“–

In some such dream of grace and light

My soul shall pass into the sight

Of the dear Gods who in the height

Of inward Being dwell;

–“–

And, joyful, at Her perfect feet

Whom most of all I long to greet

My soul shall lie in meadow sweet

All white with asphodel!

Dec 8./87 Anna Kingsford

© British Library Board (Add MS 81755, p. 19)

Kingsford’s song follows the soul as it flies on “mystical wings / While sense and body sleep” (7-8). The song begins with a seaside landscape and ends at Athena’s “perfect feet” (13). Kingsford transcribed this verse several months before her death and before her collaborator, Edward Maitland, posthumously published this mystical song. Now titled “With the Gods,” this song rests alongside Kingsford’s other visions in Dreams and Dream Stories. He also described how these particular verses “were obtained by her while dozing in her chair in the drawing-room after a day of much suffering and exhaustion” (309). Yet, there is strength in Kingsford’s handwriting within Constance’s album. Her “Carmen Mysticum” claims the page, and she fills the remaining spaces with decorative flourishes and a quotation about Athena, squeezed into the top right corner. Even as she meditates on a division between spirit and body, she leaves her mark, just as Crane had.

“Talk to me of pins, & feathers, & ladies, or rushes”

I hear that she a Book hath got –

As what young Damsel now hath not,

In which they scribble favorite fancies,

Copied from poems or romances?

– Charles Lamb, written in the Album of Miss. Daubeny

A Lady’s album having ask’d to see,

I’ve oft been tax’d for curiosity:

First you must read, or grossly you offend,

Eternal verses written to no end;

And then to put an end to all your pain,

You are compell’d, obliged to string a strain;

In which, if chance should make a beauty gleam,

‘Tis like a lily in a muddy stream.

Mr. Templeman, “Lines Written in a Lady’s Album”

The Lady’s Magazine, 1825

<16>Constance’s album represents a transitional moment from the shallow femininity associated with the “Lady’s Album” to a more progressive view of gender as fluid and flexible. As one contributor to the album wrote: “man is not all lion; woman is not all tiger-cat” (21). Contributors to Constance’s album, as the previous sections have shown, were conscious of the genre’s early nineteenth-century topoi: they compared the album to a garden; imagined the page as a cenotaph; and acknowledge the troublesome task of writing “albumenous verse,” to use Saltus’s words. The gendered nature of albums was another common theme, advocated by the title used to describe the tradition as well as the period’s novels. As Matthews teaches us, novels worked ‘to present the album not as a cultural product in its own right, but as a generic item among a young female character’s personal effects” (115). An object fraught with gendered narratives, the album was also a tool to upend the conventional gender norms associated with it.

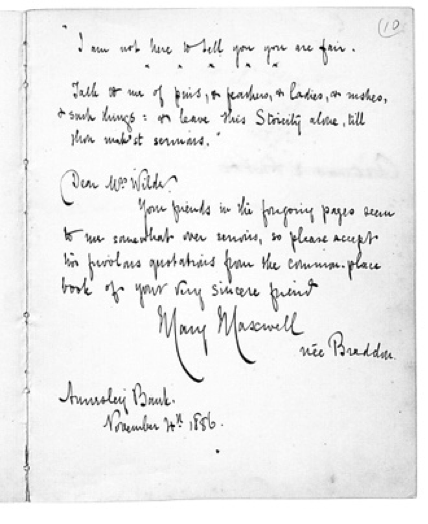

<17>The author of Lady Audley’s Secret, Mary Braddon, certainly knew a thing or two about albums. Mary Braddon refuses to participate in the conventional saccharine sentimentalism of album verse. Instead, she rebukes the entries that came before hers. Braddon (now, officially married to her lover, John Maxwell) decided not to offer album verse at all. Never one to conform to social norms, Braddon subverts gendered expectations and refuses to play the game of the lady’s album; rather than supplying saccharine verse, she picks two quotes from a respected male author, Ben Jonson, that mock the feminine frivolity assumed to be part of the album tradition.

I am not here to tell you you are fair.

*****

Talk to me of pins, & feathers, & ladies, or rushes, & such things: or leave this strictly alone, till thou mak’st sermons.

Dear Mrs. Wilde,

Your friends in the foregoing pages seem to me somewhat over serious, so please accept these frivolous quotations from the common-place book of your very sincere friend

Mary Maxwell

née Braddon

Annsley Bank

November 14th 1886

© British Library Board (Add MS 81755, p. 10)

Braddon begins by flatly refusing to flatter the album’s owner, through a quotation from Ben Jonson’s play, The Devil is an Ass. “I am not here to tell you you are fair.” After five decorative stars, she includes another Johnson quote, this time from Epicœne, or The Silent Woman: “Talk to me of pins, and feathers, and ladies, and rushes, and such things: and leave this stoicity alone till thou mak’st sermons.” In Braddon’s most well-known novel, George Talboys finds his wife’s work-box, which, among other things, contains “her album, full of extracts from Byron and Moore, written in his own scrawling hand” (40). Samantha Matthews argues, “George’s contributions should define the album as a record of authentic feeling during courtship, mediated through Romantic poetry expressing love more eloquently than the ex-dragoon could do himself” (118). This reverses the usual stereotype of naive femininity attached to albums, which stands in contrast to the “self-interested calculation” (118) we come to associate with Helen. So, it is not surprising to find that Braddon introduces an element of play into the album as she emphasizes the constructed presentation of self at the core of Constance’s collection. In this case, Braddon pulls quotations from an adjacent, and often overlapping tradition, the commonplace book (personal collections of quotations and other reading notes) that parody the obsequious flattery and trivial amusements associated with the lady’s-album tradition. In doing so, Braddon underscores how her extracts come from her own reading of respected literature, rather than the literary annual’s samples of verse (like those George borrowed). She signs her married name, Mary Maxwell, but makes sure to include her more recognizable maiden name as well.

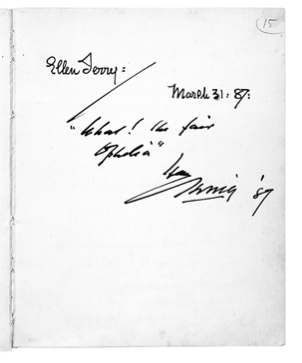

<18>The question arises: when a celebrity signs an album who is it, exactly, who signs? The public persona or the private self? Braddon’s signature simultaneously signals her married status as well as her more well-known maiden name. She signs as both the author of Lady Audley’s Secret and as Maxwell’s wife, refusing to choose between the two identities. Yet, some signatories had little choice in how they were represented on the pages of an album. For example, the page claimed by Ellen Terry and Henry Irving present a microcosm of Terry’s struggle to uncouple herself from the character her contemporaries most associated her with.

© British Library Board (Add MS 81755, p. 15)

Writing underneath Terry’s neat signature, Irving signs his name along with Hamlet’s lines, “What! The fair Ophelia.” Transcribing a line from one of his most famous performances, Irving turns the page into a stage, alluding to the fact that Irving was the Hamlet to Terry’s Ophelia. They had first performed Shakespeare’s play at the Lyceum in 1879, nearly a decade before signing Constance’s album. At the time of their signing, the role of Ophelia continued to define Terry as Nina Auerbach explains in her biography of the actress: “For better or worse, Ellen Terry became Ophelia – a role she did not like, in which she did not like herself” (237). Terry despised Ophelia’s weakness, and yet, she was under the control of Henry Irving and his Lyceum theatre. Their page in the Wilde album represents this relationship – Ellen Terry signs her name as herself, but Irving signs his with a quote from Hamlet that identifies Terry as Ophelia – the very role she had tried to escape. While Irving might have felt comfortable identifying himself as Hamlet, Terry admits that she struggled to find an identity separate from her role as an actress. In her memoirs, she writes “If I have not revealed myself, (Myself? Why even I, I often think, know little of myself!) I hope I have given a true picture of my life as an actress…”(276). Her page in Constance’s album demonstrates the ways she struggled to convey an authentic representation of herself while those around her constantly pulled her back into her character.

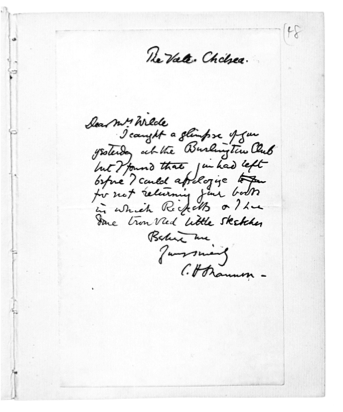

Conclusion: “A Glimpse” of Constance

The Vale Chelsea

Dear Mrs. Wilde

I caught a glimpse of you yesterday at the Burlington Club but I found that you had left before I could apologize for not returning your book in which Ricketts and I have done [illegible] little sketches.

Believe me, Yours,

CH Shannon

© British Library Board (Add MS 81755, p. 48)

© British Library Board (Add MS 81755, p. 45)

<19>Those turning to the album for a better understanding of Constance will be disappointed. In a manuscript composed through affectation, deflection, and irony, its owner is the most hidden of all the characters. Constance’s identity is reflected only through her social circle. By way of conclusion, I present three “glimpses” of Constance in her album. First, a letter pasted on one of the album’s last blank pages offers a fitting depiction of the ways that Constance is simultaneously made visible and obscured in her album. The artist, Charles Shannon – who, along with Ricketts, had borrowed the album to fill a page with sketches – catches a glimpse of Constance at the Burlington Club. Yet before he can return her “little book,” he finds that she has left. And so, he sends a letter (quoted above). A second glimpse of Constance comes in the form of Theodore Watts’s contribution that describes a beautiful mother smiling upon her child. It seems likely that Watts was describing Constance and her son Cyril, who had just turned two years old.

Yet a sight I saw outshine all other —

Saw a woman kiss a lovely child —

Saw the lovelier smile of her the mother

When " Baby smiled." (7)

Finally, a third glimpse of Constance appears underneath the journalist T.P. O’Conner’s entry. Here, Constance assumes the role of archivist. O’Conner had forgotten to date his entry, so she does it for him: “(This was written 24.7.88.)” (25). Choosing to write in pencil and enclosing her marks in parenthesis doubly downplays her contribution, which is all the more striking in an album so concerned with presence.

<20>Constance’s character emerges in small, incomplete portraits, secured as part of the performance she orchestrates. Her shadowy figure reflects her contemporaries’ assessments of her as an uncomfortable public persona – shy and quit, Constance publicly presented herself in limited view. As Mary Corelli (8) describes in her parable of Constance and Oscar (the fairy and her elephant), Constance was the quieter force, often shadowed by her husband’s presence. Nonetheless, Corelli claims to find her the more interesting of the two.

She does not seem to stand at all in awe of her Elephant lord. She has her own little webs to weave––silvery webs of gossamer––discussions on politics, in which, bless her heart for a charming little Radical, she works neither good nor harm. . . . To me she is infinitely more interesting than the Elephant himself . . . one never gets tired of looking at the lovely Fairy who guards and guides him. (168)

Compare Corelli’s fascination to Constance to Comtesse de Brémont’s brusque dismissal of her host, who she claimed, “speedily sank in to the background, completely forgotten and eclipsed by the brilliant glow of her husband’s eloquence” (90). And yet, these depictions reveal how Constance was an integral part of her husband’s performance, even if she rarely got credit for it. Hers is a common story of women married to famous men. It remains unclear what role Constance played in her husband’s work, but the Morgan Library holds a suggestive manuscript of “The Selfish Giant,” written entirely in Constance’s hand with small marginal corrections made by Oscar. The short story would be published as part of The Happy Prince and Other Tales. “Tantalizingly,” Moyle asserts, “there are several aspects of the text that suggest that the manuscript may reflect collaboration” (136). In another respect, Constance certainly collaborated with Oscar in so far as they cultivated a now canonical image of aestheticism. She held at homes, collected autographs, and crafted a simple cover to encase her album. There is creativity in collecting and documenting, organizing and sorting. And there is creativity in cultivating a public identity. All of which goes to support To-Day’s assertion that Constance “may be truly called an apostle of the beautiful” (93).