<1>Nineteenth-century mystery, a genre always predicated both on the idea that we don’t know something but that we can come to know it, offers us epistemologies—reading clues, seeing patterns, investigative reporting—that we continue to use today in grappling with sexual violence in our culture and on our campuses. I recently realized connections between my research on the mid-nineteenth century boom in mystery narratives and our efforts in the present moment to document sexual violence when, as Vice-Chair of my Academic Senate, I served on my institution’s Title IX implementation committee. Working with faculty on the processes and effects of Title IX mandatory reporting, I was reminded of the ways in which nineteenth-century mysteries highlight violence suffered by female characters, but also how they suggest that these characters’ experiences can foster detective skills necessary for exposing and combatting such violence. This connection helped me to rethink my initial alarm at being told that I was now a mandatory reporter of any sexual violence disclosed to me on my campus, an alarm shared by many of my fellow faculty members, who (like many faculty members across the United States) worried that we were being asked to surveil our students in potentially retraumatizing ways.(1) My work with nineteenth-century mystery narratives has led me to understand Title IX implementation as a huge social project (one recently strengthened by Department of Education revisions) in which we all do need to see ourselves as detectives, but not Foucauldian detectives—those figures of hegemonic authority, surveillance, and judgment.(2) Instead, we can follow the ways in which the mid-nineteenth century mystery offers a form of master-perception that is rooted more in empathy and identification with than identification of, and we can act like the community-focused female detectives in the novel of urban mysteries, who acquire skills in watchfulness in order to make sexual violence more visible and to challenge it. The graphic visibility of violence in nineteenth-century mysteries, especially in their most inexpensive and popular manifestations, can help us to understand and historicize the central tenet of both Title IX and #MeToo: that confronting and combatting sexual violence is predicated on its exposure and documentation.

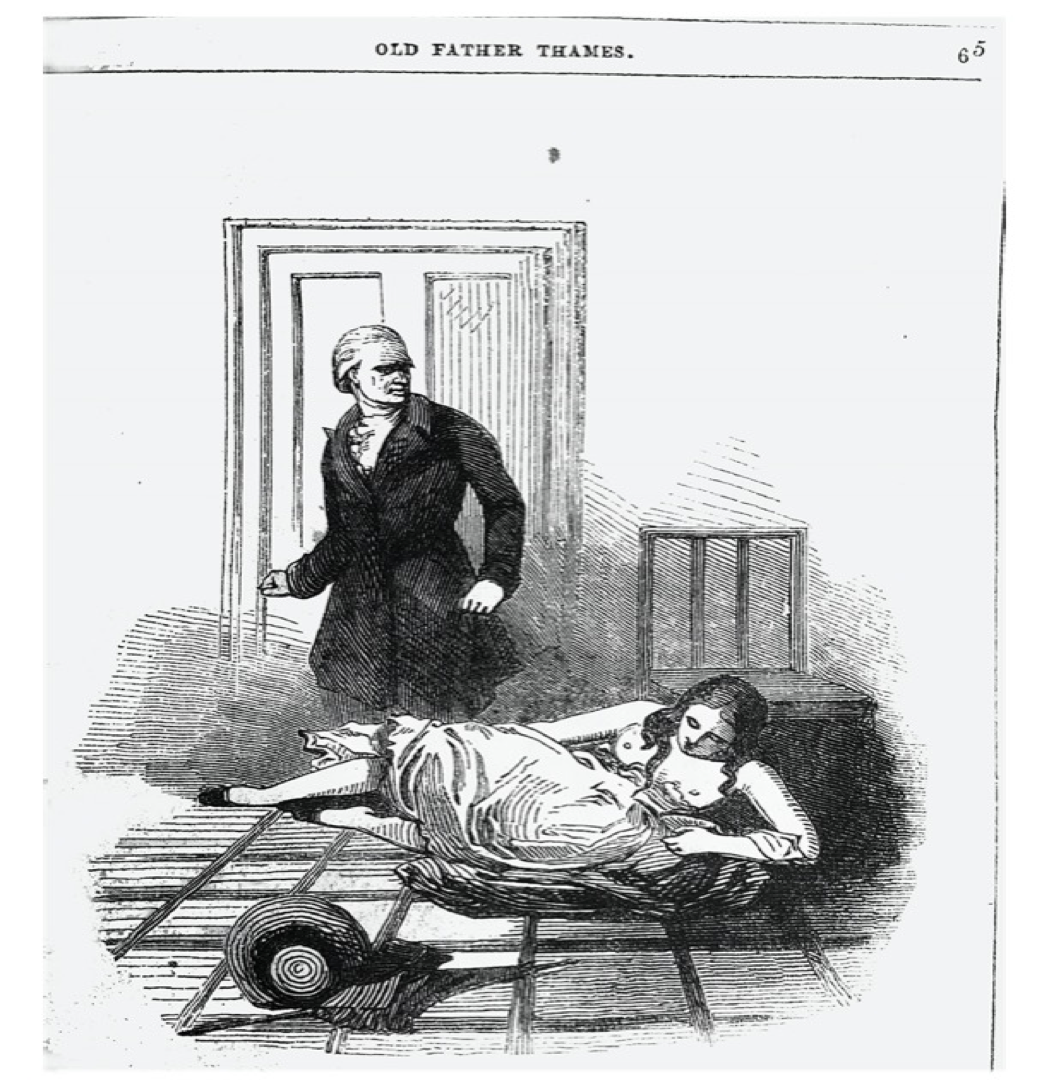

<2>The visibility of sexual violence in mid-nineteenth century penny mysteries can seem especially startling when contrasted with the silences, ellipses, euphemisms, and understatements about violence we encounter in much of the nineteenth-century literature that forms the focus of academic study. We can find such silences even in novels that created a stir with their apparent frankness, such as Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847). Jane, threatened by Mr. Rochester with sexual violence, refers rather coyly to the possibility of his falling into “wild license” and, even in the fraught moment in which she notes “the present—the passing second of time—was all I had in which to control and restrain him” for “a movement of repulsion, flight, fear would have sealed my doom,—and his,” feels fully confident in her power to defuse him. Indeed, she is so assured of her power that while she finds the moment “perilous,” she also notes it is “not without its charm” (258). In Jane’s conviction of her ability to handle Rochester, we can hear an echo of the idea that truly virtuous women should be able to repel the violence that comes their way, an idea that pervades much nineteenth-century literature and culture. Contrast Brontë’s scene to a scene of wild license in Thomas Frost’s contemporaneous The Mysteries of Old Father Thames (1848), in which fifteen-year old Lolah Hastings, having been spotted by sexagenarian pedophile Colonel Eldrington (“one of those pests of society who . . . seek to revive the vigour of past days by stimulating their passions by the seduction of females of extreme youth”), is decoyed by him into a procuress’s house and violently raped (68; pt.9). Despite the virtuous girl’s spirited defiance of her attacker—“I will not submit to this infamy while I am able to resist!” she cries (72; pt.9)—she is finally unable to fend him off:

Long but vainly did Lolah Hastings struggle with her persecutor; in vain her resistance—in vain her screams, for not a sound passed beyond the four walls of that chamber of mystery and guilt. With her shining black hair hanging dishevelled on her shoulders, with her clothes torn, and her face and neck suffused with burning blushes, she was thrown upon the matted floor of that strangely-contrived apartment, and the libertine colonel succeeded in the penetration of his design. (73; pt.10)

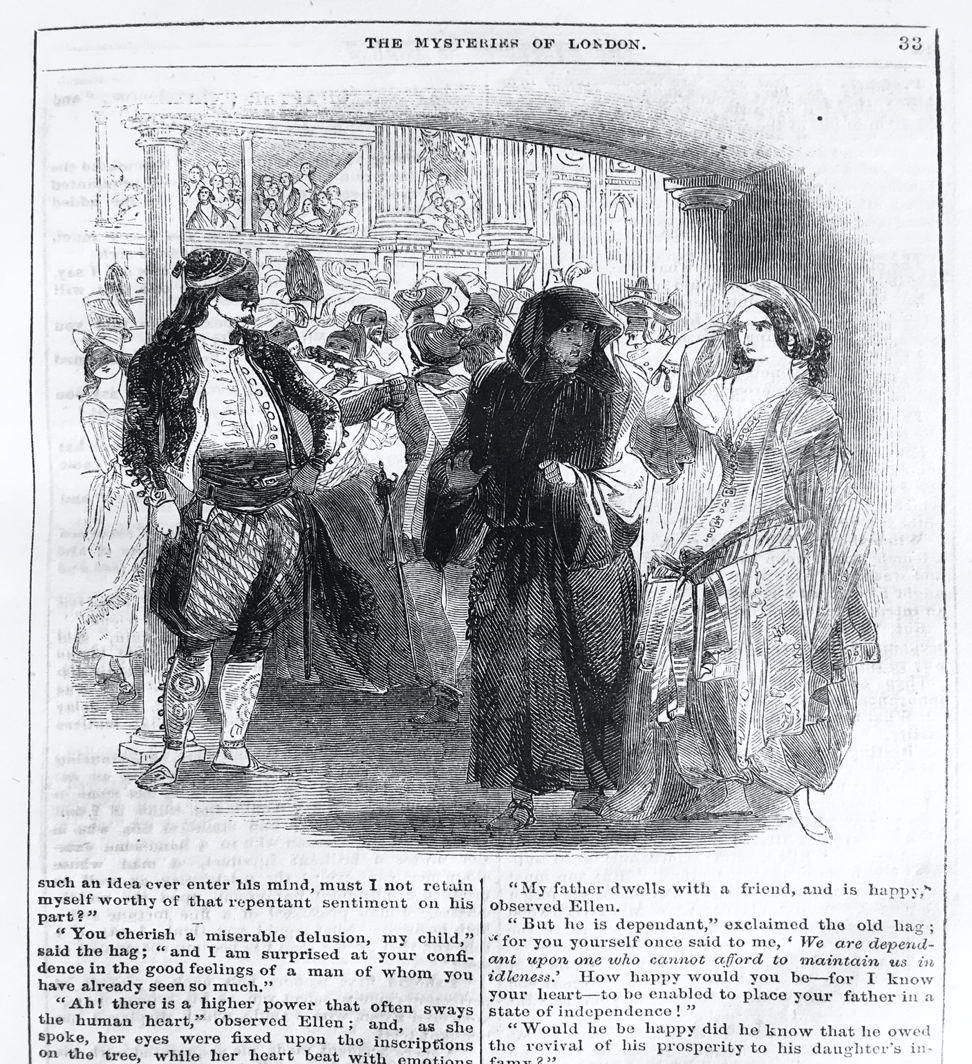

The violence of the colonel’s penetration of his design—the attack that leaves Lolah’s hair disheveled, clothes torn, and body thrown—is rendered graphically twice over in Frost’s serial, appearing in both prose description and in the cover illustration of the preceding installment [see figure 1]. While such renditions clearly show us the shocking content that made mid-century penny fiction notorious—and that gave rise to such labels as the “penny blood” and (a little later) the “penny dreadful”—they are also of a piece with Frost’s general mission of exposing what too often goes ignored.

<3>Indeed, Frost throughout aligns himself with Asmodeus, a demon who can see through roofs and walls (and who thus functions as a kind of patron-demon of the Mysteries). Proclaiming that, “Asmodeus-like,” he will “penetrate the abodes of vice and misery” and “reveal the mysteries” that have been concealed (3-4; pt.1), Frost explicitly meditates on the exposure of sexual violence:

The whole subject is a painful one; but shall we suffer evil to exist unnoticed, and to spread its hideous ramifications throughout the whole framework of society, for fear of shocking the sensitive by its exposure? Let us choose the lesser of two evils; to unmask an abuse is the first step to its removal. (131; pt.17)

Such envelope-pushing exposures, too often only recognized as part of the commercial lure of penny fiction, were also politically radical. Frost, a laboring-class Chartist who produced a number of city-mysteries in the 1840s, turned Lolah Hastings into a character whose experiences of violence culminate in a challenge to cultures of misogyny. The mixed-race daughter of one Colonel Hastings, Lolah is kidnapped as a child from her father’s house and grows up a penniless and abused street dancer. After briefly being restored to her father—during which time she attends the school where she catches the eye of the “libertine colonel”—her father is murdered, and her rape leads to her becoming a courtesan. Lolah, however, not only survives her rape (and manages to knock her attacker unconscious during his second attempt), but through some canny detective work is also able eventually to bring her procuress to justice. The procuress ends up transported for seven years, while Lolah ends up married to aristocrat Norman Ashley. Frost includes a series of scenes during Norman’s courtship of Lolah in which the couple frankly discuss these events. When Lolah, who notes that “misfortune in woman is too often visited with reprobation rather than with the pity which it surely deserves,” rather anxiously tells Norman that she was “vilely and brutally outraged by one whom the world calls a gentleman,” and afterward accepted “an offer of protection” in order to survive, Norman responds by hoping that she does “not think so meanly” of him as “to suppose that the occurrence of such misfortune could tend to diminish [his] affection” (186; pt.24). After Norman assures her, “your candour has secured you the continuance of my esteem, and no circumstances could ever diminish the ardent passion with which you have inspired me,” (an assurance that prompts Lolah to swiftly send her current protector packing), Norman overtly declares that he has “no right” to pass any judgment on her for “what may have occurred before [they] were acquainted” (187-88; pt.24). Such discussions and sentiments, recurrent in the urban mysteries, run strikingly counter to the dominant account of how sexual violence is represented in mid- and even late-nineteenth-century literature. We might immediately think, for instance, of a work like Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), which, a full four decades after Frost’s novel, is utterly silent about the details of Tess’s rape, and sees Tess’s new husband Angel, after hearing her account of Alec d’Urberville’s attack, coldly reject her, claiming she suddenly seems to be a different person.(3)

<4>The graphic depictions and discussions we see in Frost’s Thames are foundational to the urban mysteries as a whole: indeed, the novel that sparked the genre, Eugène Sue’s Les Mystères de Paris (1842-3), opens with an explicit warning about the unvarnished delineations to be found in the pages to come. “This beginning announces to the reader that he must here witness sinister scenes,” cautions Sue’s narrator in his opening sentence, underscoring the novel’s twinned mission to expose scenes generally concealed and to capitalize on “the sort of fearful curiosity that is sometimes provoked by terrible spectacles” (I: 2). The sinister scenes we find in these narratives regularly display and even focus on violence against women, a focus that continues to inform popular mysteries today. However, as Frost’s Thames demonstrates, even as the urban mysteries exhibit violence much more explicitly than do the more middle-class fictions of the nineteenth century, they also directly engage with the sources of such violence and offer challenges to it. In so doing, the urban mysteries both highlight distinctions and make connections between forms of violence suffered by women (and men) across the social spectrum. As they offer stories that exhibit a variety of forms of violence that enslaved women, working-class women, and middle-class women could be subject to, they also provide moments of nineteenth-century intersectionality, clearly showing what Kimberlé Crenshaw has called instances in which “race, gender, and class domination converge” (1246). By looking back at these mysteries in our #MeToo moment, we can find not just examples of Victorian sexism and misogyny, but also ways in which Victorian culture was already acknowledging sexual violence as “social and systemic” rather than “isolated and individual,” and imagining women with differently intersecting experiences and identities as agents of change who could readily detect, recount, and challenge forms of everyday aggression (Crenshaw 1241-42).

<5>The sinister scenes Sue depicts in his Parisian Mysteries which show us violence against women (and that also expose systemic connections between forms of violence) begin in the novel’s opening pages. The very first scene shows us the narrative’s hero, master-of-disguise, and proto-superhero Prince Rodolphe (posing as an artisan fan-painter), emerging from a dark doorway in the hardscrabble Cité to save a young prostitute, Fleur-de-Marie, from a threatened beating by the rough Chorineur (or “Stabber”), an ex-convict who has been demanding that the young woman buy him a drink. When Rodolphe, after besting the Chorineur in a fight, takes them both to a local bar for some refreshment, Fleur-de-Marie relates to them a horrifyingly detailed account of the violence that she suffered as a child abandoned on the streets of Paris, and how she was only recently, at the age of sixteen, drugged, raped, and sold into prostitution. As the men listen to Fleur-de-Marie’s story, the Chorineur demonstrates his redeemable nature by vociferously registering his commonality with the prostitute as a victim of social inequality. Exclaiming, “it is really surprising, my wench, how much we resemble each other!” the Chorineur eventually apologizes for his behavior, saying “how sorry I am, that I threatened to beat you just now, and frightened you” (I: 33, 39). Fleur-de-Marie’s compelling testimony, her “recital, made with such painful frankness,” has the effect of making alliances and countering violence (I: 46).

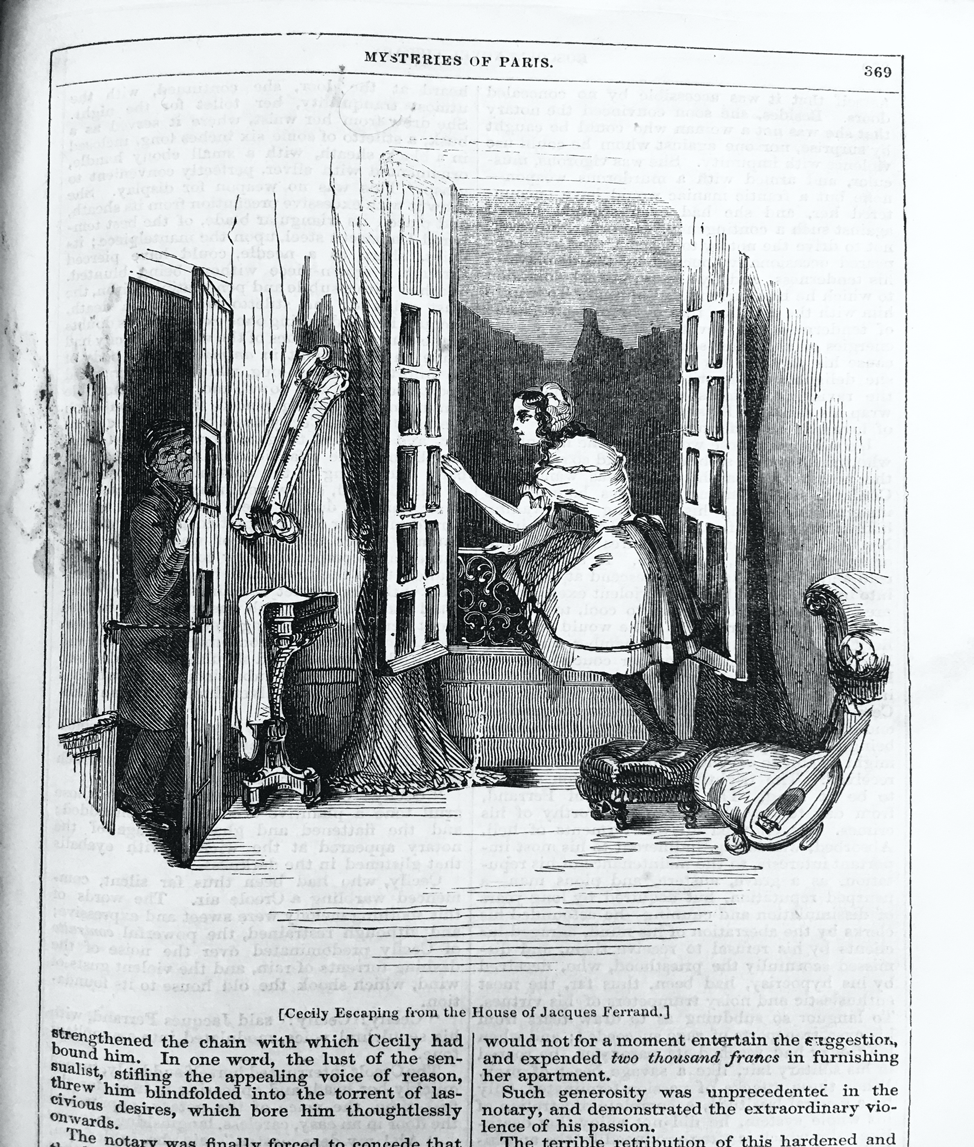

<6>As the novel progresses, we encounter many more female characters from across the social spectrum who suffer physical and sexual violence. While some of these characters (including Fleur-de-Marie) are eventually destroyed by the violence they have suffered, many exhibit impressive resilience, and some even transform into vigilante figures who rival Prince Rodolphe himself in their ability to detect things and perform masked vengeance. The most powerful of these vigilante characters is the beautiful and ruthless Cécily. A mixed-race former American slave, Cécily was virtuously fending off increasingly “brutal attempts” by her slave master to rape her when Rodolphe, fortuitously traveling through the American South, first encountered her (V: 70). Speedily rescuing both Cécily and her slave fiancé David, Rodolphe brings them to Europe and employs David (who had been educated in medicine) as his personal physician. Although once away from the plantation, Cécily—in a rather abrupt move—suddenly rejects David to pursue a villainous path, the novel makes much of her remarkable talents: she possesses a “plastic, adroit, insinuating mind,” “an intelligence so wonderful that in a year she spoke French and German with perfect ease,” and “an audacity and courage proof against everything” (V: 71). Indeed, she is so formidable that Rodolphe himself seeks her help in vanquishing the novel’s most villainous master plotter and sexual predator, a notary named Jacques Ferrand. Cécily infiltrates the malefactor’s house in a titillating disguise and tricks the notary into giving her concrete evidence of his crimes before—rather poetically—deliberately goading him into such a state of satyromania that he actually perishes of it [see figure 2]. Cécily agrees to enact her sexy masked vengeance on Ferrand because she is “sincerely indignant at the recital of the infamous violence,” especially towards women, perpetrated by the arch-villain (V: 72). Notably, in his depiction of Cécily, Sue both follows and exposes the racist idea of the supposed licentiousness of female slaves. While in the end he can’t seem to let Cécily enact her sexualized vigilantism without first transforming her into a character who is truly, at heart, sexually promiscuous, the shocking and rather unconvincing abruptness of her transformation from the chaste, virtuous partner of David into a wanton lone-ranger villainess-vigilante highlights (even if unwittingly) the artificiality of such racist constructs.

<7>Sue’s Parisian Mysteries was fast to become perhaps the most popular nineteenth-century novel in any language.(4) As translated editions appeared throughout Europe and America, Sue’s novel inspired a new, international genre of narrative mystery and generated a transatlantic “mysterymania” for narratives purporting to expose the burgeoning secret underworlds and economic inequalities shaping the rapidly urbanizing mid-nineteenth century.(5) These mysteries regularly followed Sue in including scenes of violence against women alongside scenes that feature female vigilantes and detective characters bent on uncovering and challenging such violence. Indeed, the Mysteries importantly incubate the literary detective by exploring characters—both male and female—who live on the margins of society but gain power by developing their detective skills. These proto-detectives often draw on their experiences of social disempowerment to help them to out-see and outwit the genre’s many “oxymoronic oppressors” (David S. Reynolds’s term for the character type of the “outwardly respectable but inwardly corrupt social leader” [86]).(6) Collectively, the Mysteries champion an empathetic form of master-perception, one rooted in using one’s own experiences to strengthen one’s imaginative ability to inhabit other minds. We can see empathetic master-perception especially informing many of the female detective characters that emerge in the hundreds of British and American urban mysteries inspired by Sue’s Parisian chronicles, in narratives set in burgeoning metropolises (such as Frost’s Thames and G. W. M. Reynolds’s The Mysteries of London [first series, 1844-46], or, across the Atlantic, Ned Buntline’s The Mysteries and Miseries of New York [1848] and Osgood Bradbury’s The Mysteries of Boston [1844]), but also in factory towns (Bradbury’s The Mysteries of Lowell [1844]), and even small hamlets (Philip Penchant’s The Mysteries of Fitchburg [1844]).

<8>The ways in which empathic master-perception can lead to cross-class coalitions in the Mysteries is powerfully showcased in Reynolds’s The Mysteries of London, a gargantuan serial that ran under a number of different titles from 1844 to 1856 and was the most popular novel of mid-century England, famously outselling Dickens’s 1840s offerings.(7) In his London Mysteries, Reynolds, like Sue, depicts the many kinds of violence that women could be subject to in the modern world (violence suffered at the hands of both male and female perpetrators). He also, however, expands upon Sue’s interest in female characters who not only survive violence but whose experiences help them to become powerful detective-advocates for themselves and others. Among the many active, resilient, and powerful female characters in The Mysteries of London, Eliza Sydney, Diana Arlington, and Ellen Monroe comprise a particularly fascinating interconnected trio. All three of these major characters experience social and/or sexual falls, but none are destroyed by their experiences; instead, they are able to thrive and prosper, and to use their varied life experiences to develop skills in detecting and protecting themselves and others from villainy.(8)

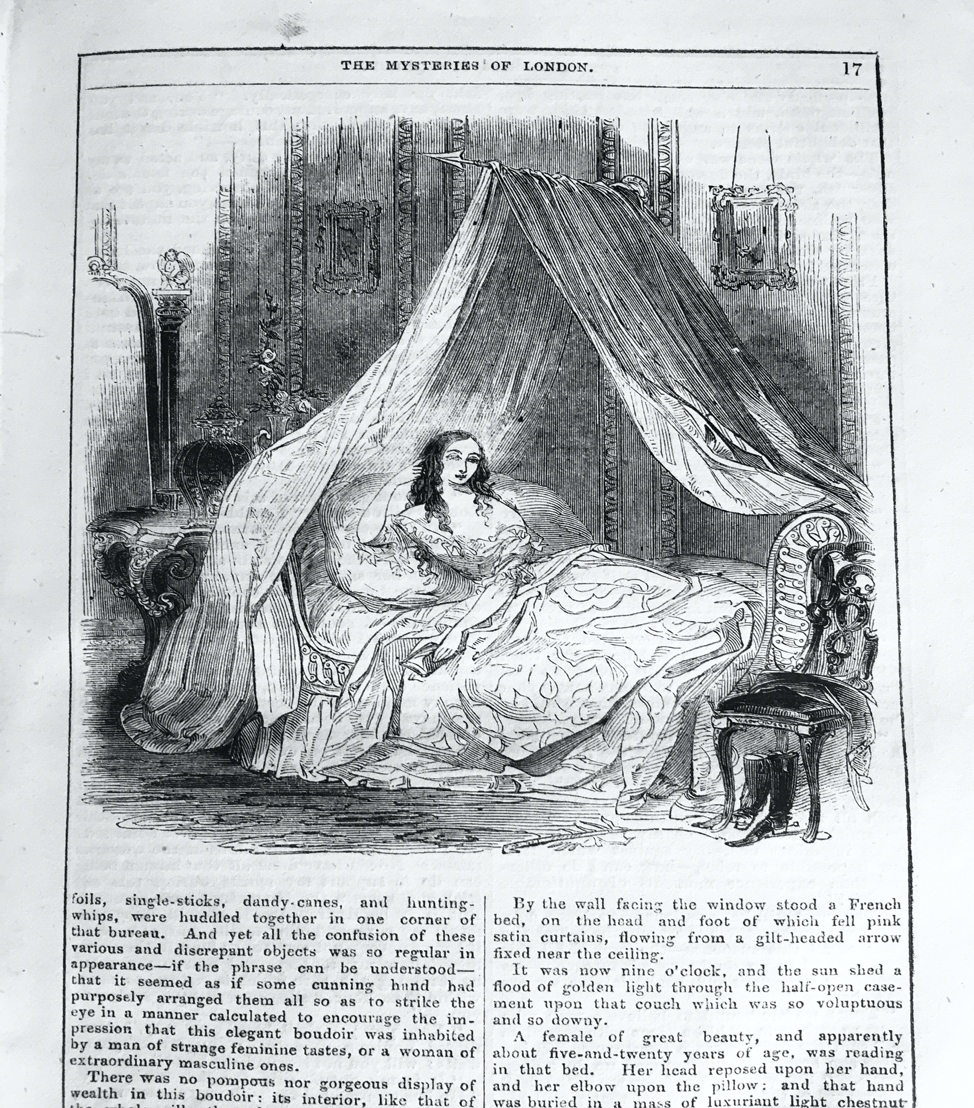

<9>We first meet Eliza Sydney in the opening installment of Reynolds’s novel, although we don’t know it: she’s running around the city cross-dressed as “Walter” Sydney, and it is not until the third installment that Reynolds delights in revealing the stalwart Walter to also be the nubile Eliza [see figure 3]. Eliza is eventually sentenced to two years in Newgate for the complex inheritance-fraud scheme concocted by her guardian that had her impersonate her deceased brother for several years, the full details of which she was only partially aware. Readers might expect such disreputable behavior as cross-dressing and its subsequent punishment to destroy fully the reputation of an upper-middle class character like Eliza. However, after Eliza serves her sentence, she returns to her comfortable Upper Clapton villa, handily fends off repeated sexual attacks by Montague Greenwood, the novel’s master-plotting/master-of-disguise arch-villain, and eventually moves to Italy where she marries royalty and becomes the Grand Duchess of Castelcicala (notably, the Grand Duke proposes to her after finding out about her time in prison). As the powerful and wealthy Grand Duchess, Eliza builds a kind of international spy network to keep an eye on London happenings—and in particular on the doings of Montague Greenwood, whose Italian valet, Filippo, is in Eliza’s pay.

<10>Eliza’s surprising ascent from disgraced jailbird to royalty occurs as a direct result of her accepting the help of a sharp-eyed, sharp-witted courtesan, Diana Arlington. We meet Diana in the novel’s second installment, and learn shortly thereafter her history: an educated, middle-class young lady, she was seduced and abandoned by Montague Greenwood (who was simultaneously ruining her father in a financial con). While Diana’s reputation does suffer as a result of the seduction—following her father’s suicide, she becomes a courtesan after finding out that no one will employ her otherwise—Diana nevertheless enjoys considerable power over her fate. When we first meet her, she’s living under the protection of one Sir Rupert Harborough, but after realizing his moral turpitude she coolly leaves him, and selects (from a remarkably large prospective pool) a new protector, the Earl of Warrington. This relationship soon flourishes into one of deep mutual respect, and Diana uses the resources available to her as the wealthy Earl’s companion to befriend and aid Eliza before she’s sent to prison (having ferreted out evidence that Eliza is more innocent than guilty), and then to send Eliza to Italy after she is released. Eventually, the Earl of Warrington asks Diana to marry him, and Reynolds writes in succinct commentary on both Eliza’s and Diana’s happy outcomes: “Such are the strange phases which this world presents to our view! That same Fortune, who, in a moment of caprice, had raised an obscure English lady to a ducal throne, placed, when in a similar mood, a coronet upon the brow of another who had long filled a most equivocal position in society” (II: 94-95; pt.64).

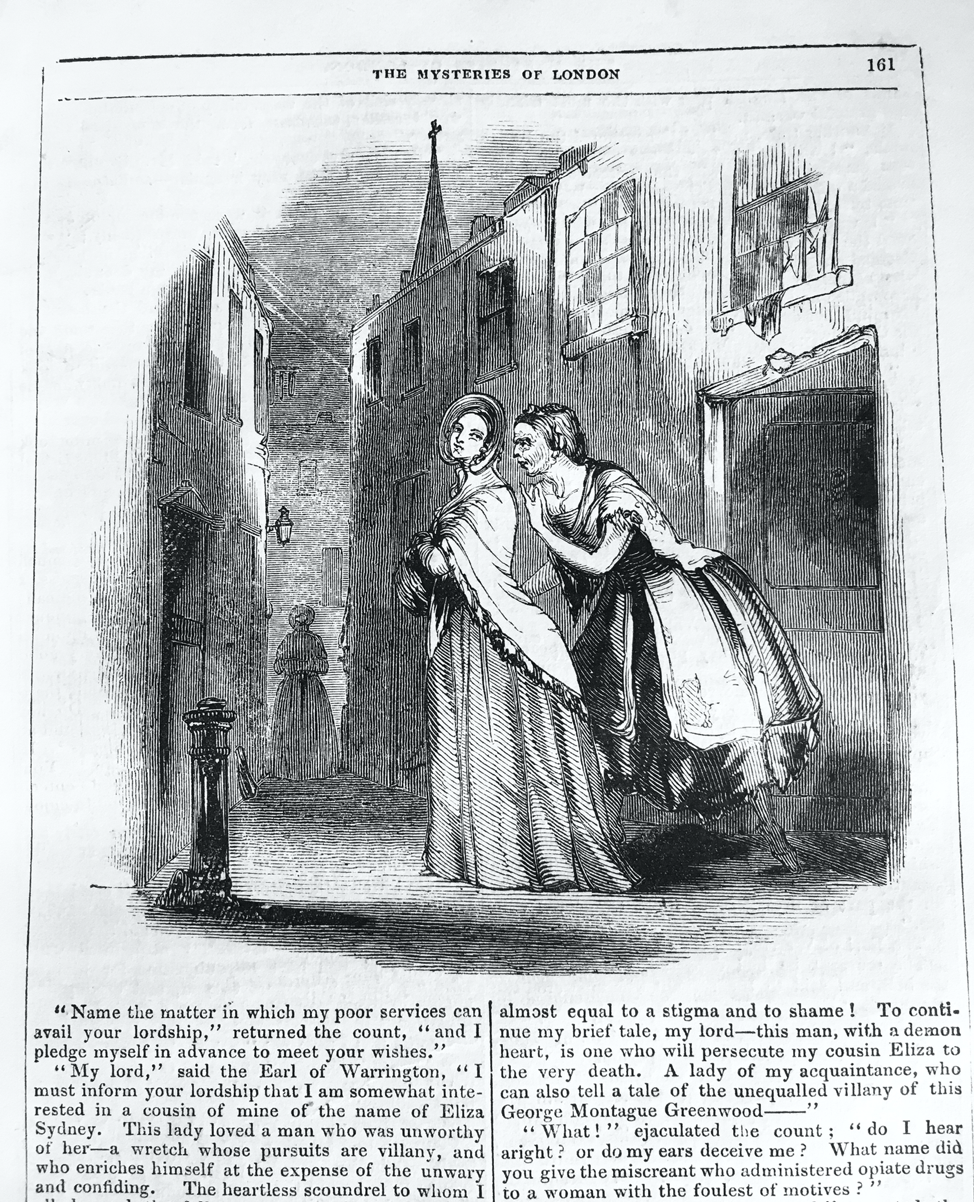

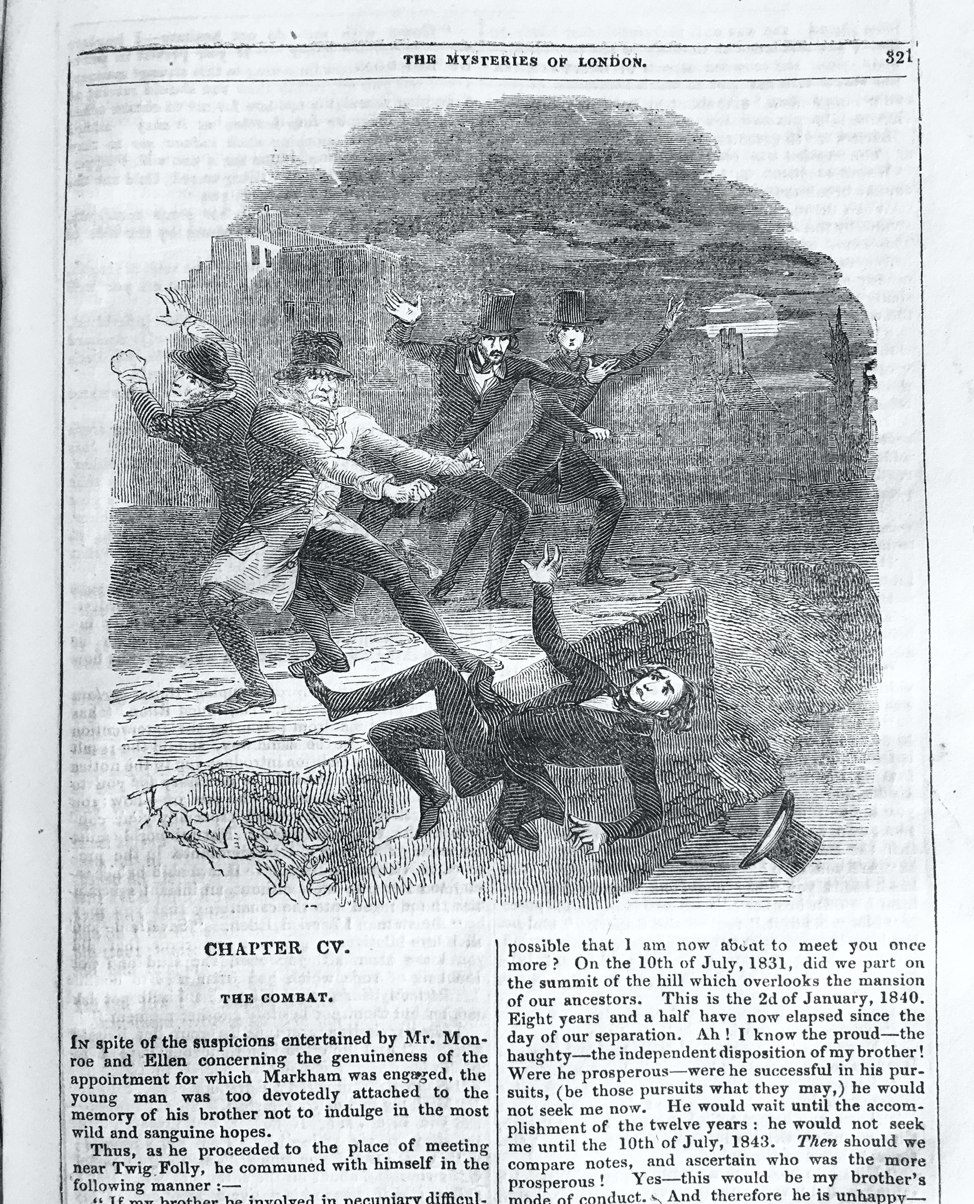

<11>Such capricious fortune also smiles on Ellen Monroe, who, like Diana Arlington, inhabits a most equivocal position in the novel. After her father, like Diana’s, is ruined financially by Montague Greenwood, Ellen finds herself in penury, and as she scrambles to survive she allows herself slowly to be groomed by an “Old Hag” procuress into prostitution [see figure 4]. When Ellen finally agrees to one night with a paying customer (none other, of course, than Montague Greenwood), she becomes pregnant. However, just like Eliza and Diana, Ellen is not destroyed by her social and sexual fall, or by having a child while unmarried. Instead, she demands that Greenwood support the baby (he does), and becomes a mesmerist’s assistant, a ballet dancer, and finally, a renowned actress. Unknowingly helped by Eliza Sydney’s spy network, Ellen successfully fends off subsequent sexual attacks by Greenwood, and she boldly tracks down and calls out other potential sexual predators who threaten her [see figure 5]. Like Cécily before her, Ellen also engages in masked vigilante action. When she detects, for instance, that ostensible hero Richard Markham is about to walk blindly into a trap, she uses the skills she has learned from the stage to venture out to Holywell Street, coolly purchase “everything suitable to form a complete male disguise,” and saunter off “without exciting any particular notice” to save her friend (I: 319-20; pt.40). Drawing upon the “considerable amount of fortitude and self-possession” that “she had acquired . . . from the various circumstances in which she had been placed,” and wielding a loaded pistol (which she “learnt to fire . . . at the theater”), Ellen handily rescues Richard (I: 320; pt.40) [see figure 6]. Finally, after blackmailing Greenwood into secretly marrying her so as to legitimize her baby (II: 165; pt.73), and after years of serial adventures, Ellen, having become Eliza’s friend, learns of Eliza’s detective network. “Are you angry with me for having thus placed a spy upon the actions of your husband?” Eliza asks Ellen. “Oh! no—no,” Ellen replies, “on the contrary, I rejoice! For doubtless you have saved him from the commission of many misdeeds!” (II: 412; pt.104). In this moment, Ellen clearly acknowledges the value of watching, noting, and recording misdeeds in order to be able to help curtail them.

<12>Such scenes, characters, and coalitions were also explored and developed by a vigorous and diverse set of American writers. Again and again the transatlantic Mysteries show women’s power as inextricably connected to their abilities in master-perception and deception in ways that do not have to do damage to their reputation and that often help them redress and foil instances of sexual assault and violence against women. These mysteries regularly celebrate the ascendant social trajectories of marginalized and threatened female characters who draw on their experiences in order to foster impressive abilities with the reading and manipulating of signs. Socially or sexually fallen characters, factory girls, and slaves can become masterminds behind both domestic plots and international intrigues in American Mysteries. Seeming prostitutes such as Ellen Bruce in Tom Shortfellow’s Mysteries of New York (1845) can turn out to be female vigilante Robin Hoods; promiscuous wives such as Fanny Gardner in Buntline’s The Mysteries and Miseries of New Orleans (1851) can take down entire filibustering missions in Cuba; and forty-year old chamber-maids, such as Tabitha Jones in Bradbury’s Second Series of the Mysteries of Boston (1844), can disguise themselves as courtesans to foster cross-class alliances. Southern heiresses, such as Ella Howard in Philip Penchant’s The Mysteries of Fitchburg (1844), can likewise disguise themselves as courtesans in order to punish nefarious and deceitful men. Visiting the hamlet of Fitchburg, Ella takes on the villainous Ruel Lenox and his father, both serial seducers, by posing as a sexually available woman. As Ella completes the “fatal snares she was continually setting for the destruction of Lenox,” the narrator applauds her canny ability to out-deceive the villain: “they walked together, the deceiver and the deceived! The searching eye of Ella Howard could read the inmost thoughts of Ruel Lenox! And he, who had thought to deceive, was himself deceived!” (19, 23). Although Ella herself notes at the end that “mine has been a fearful part to act,” after successfully punishing both sexual predators, she peacefully decamps back to the South to enjoy her inheritance (25).

<13>In ways that anticipate the #MeToo movement’s aims of making sexual violence and harassment visible while also fostering female solidarity, Sue’s Cécily, Reynolds’s trio of powerful fallen women, and characters like Tabitha Jones and Ella Howard show how female vigilante detective action in the Mysteries generally involves community-focused women bent on making violence against women more visible as they work to combat it. We can find many more instances of this across the genre. Big Lize in Ned Buntline’s The Mysteries and Miseries of New York (1848), who works as the seductive bait for a panel thief, uses her skills in deception to protect the novel’s suddenly impoverished heroine from seduction.(9) Mary Trevor in J. Wimpleton Wilkes’s The Mysteries of Springfield (1844) draws on her own experience of being seduced to gain the knowledge necessary to foil her seducer’s next plot, thus protecting Springfield’s romantic heroine from harm.

<14>Such depictions of female heroism and collectivity were clearly noted by other writers intent on exposing sexual violence and calling for social change. Harriet Jacobs, for instance, mobilizes Mysteries tropes and structures to enhance her proto-feminist message in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861). Jacobs echoes the Mysteries in observing how experiences of violence and subjection can heighten detective skills. “Slaves, being surrounded by mysteries, deceptions, and dangers,” she writes, “early learn to be suspicious and watchful, and prematurely cautious and cunning”; a good thing, she argues, for skills in watchful craftiness constitute “the only weapon of the weak and oppressed against the strength of their tyrants” (155, 101).(10) Moreover, Jacobs explicitly positions herself as a master-perceiver, casting her struggle with her master—who constantly threatens her with rape—as a kind of mystery plot, a “competition in cunning,” in which she plays the role of a sharp-eyed master of disguise who eventually and handily outwits her adversary (155). “Competition in Cunning” is the title of chapter 25 of Incidents; even before this, Jacobs sets herself up as an adversary who is more than her master’s equal in cunning, perception, and disguise. “Thus far I had outwitted him,” she notes when she hides in her first attic storage space right in her town, while he rushes out of town to search for her, “and I triumphed over it” (100). When she finally escapes to New York—the “City of Iniquity” (199)—she is well able to penetrate a false letter: “I knew, by the style, that it was not written by a person of his age, and though the writing was disguised, I had been made too unhappy by it, in former years, not to recognize at once the hand of Dr. Flint,” and asks “did the old fox suppose I was goose enough to go into such a trap? Verily, he relied too much upon ‘the stupidity of the African race’” (172). Even as Jacobs relates the horrors of taking cover in her punishingly small hiding places—the “dismal hole(s)” in which she dwells for years—she also recasts herself as a kind of Asmodeus who, literally seeing through roofs and walls, “command[s] a view” of the world and bears witness to many unfortunate histories, including bondwomen being raped by their masters and then turned out (113, 100).

<15>The act of bearing witness to such violence—of exposing it, of acknowledging its widespread, systemic presence in our world in order to challenge it—is one of the central projects of the nineteenth-century mystery, as well as the central purpose of both Title IX mandatory reporting and the #MeToo movement. Sensational penny mysteries, in exploring the potential of disadvantage and disability to foster skills that could lead to greater advantage and ability, and in highlighting collective action, offer unexpectedly candid views of sexual violence in the nineteenth century; they also provide a counterpoint to the narrative of Victorian silences on the subject of sexual assault. Like #MeToo testimony, these mysteries offer shocking narratives that are also an important kind of evidence. They correct silences found in canonical works by writers such as Dickens and Hardy, and they can help us see more clearly the radical feminism in genres they intersect with, including the slave narrative (especially Jacob’s Incidents) and the later “sensation” novel (including those by Mary Elizabeth Braddon).(11) Attending more closely to such popular but understudied literature in our classrooms and our research can help us to rewrite our understandings of silences about sexual violence both in the nineteenth-century and today.

Acknowledgement

My sincere thanks to Marlene Tromp, whose innovative panel on “Narrativizing Victorian Violence in the #MeToo Era” at NAVSA 2019 allowed me to reflect on these connections and present the first version of this piece.