<1>In 1885, the New Woman protagonist of George Meredith’s Diana of the Crossways posited a question that reframed cultural debates over the state of gendered relations: “Could the best of men be simply a woman’s friend?” (Meredith 364). This speculation regarding the possibility of heterosocial friendship had echoed throughout the nineteenth century.(1) By the 1880s, however—in the wake of evolving cultural ideals of masculinity and femininity; growing demands for the social, legal, and political equality of women in the public sphere; and burgeoning scientific interest in theorizing and essentializing sexual instinct—debates regarding such friendships took on new, vitally important resonances. Might this imagined relation—centered on assumptions of mutual consent, restraint, and rationality—serve as a resolution to the much-narrated battle between the sexes? And, implicit in Diana’s unanswered question—uttered with no small amount of exasperation after multiple sexual assaults, the public failure of a stifling marriage, and the repeated social insults of the scandal that follows—is another. How to cultivate a brave, new heterosocial world in a violently heterosexualized one fraught with the cyclical risk of violation?(2)

<2>Such questions continue to reverberate in new forms today. The #MeToo movement has illuminated old narratives of sexual exploitation and the abuse of power persistently embedded in our workplaces and beyond. In its wake, the promise of a modern heterosocial public sphere free from this violence, at worst, only appears to mask its pervasiveness further and, at best, remains a utopian vision toward which we still strive. In sharing their stories, most survivors hoped to spark an “empowerment of empathy,” as the founder of the movement, Tarana Burke, has noted (qtd. in Murray). In Burke’s vision, the spectacle of disclosure was meant to be only the first step in a complex process of communal accountability, healing, and change. Accountability, however, has been as slippery as personal narratives have been abundant.

<3>While some individuals have no doubt attempted to grasp the cultural roots of sexual violence, many instead have reverted to the Victorian “solution” of separate spheres and chaperonage: men should simply refuse to be alone with women.(3) Such tactics prove not only reductive—erasing the existence of sexual trauma amongst members of the LBGTQ community, male survivors, and female perpetrators, to name only a few oversimplifications—but also punitive and discriminatory. They actively dismiss the issues that led to the movement and reveal assumptions that either “women are lying” or “men are incapable of not sexually harassing or assaulting women if the opportunity arises” (Senecal). Indeed, such logics are so regressive that they evoke the threats of rape deployed against women entering male professions by mid-nineteenth-century conservatives. In his infamous 1862 article in Blackwood’s Magazine, “The Rights of Woman,” William E. Aytoun speculates about the future of the “maiden” female doctor. He relishes the possibility that “under professional pretexts, she might be decoyed into any den of infamy. Nor would the public sympathy be largely lavished upon the victim of such an outrage” (197). Within Aytoun’s terms, rape becomes an inevitable consequence, and just punishment, for women who mingle with men unsupervised in the pursuit of professional ambitions.(4) As Victorianists know, outrage surrounding the prevalence of sexual trauma and the inevitable backlash has waxed and waned not just for decades, but for centuries. This historical cyclicality speaks to the elusiveness of progress and the cultural embeddedness of patriarchal entitlement: nevertheless, she persisted, but much that she resisted remains nevertheless.

<4>Just as backlash to the #MeToo movement evokes a return to Victorian assumptions regarding the separation of the sexes, however, rereading Victorian literature in light of this current moment allows us to recover proto-feminist Victorians’ own rebuttals to the status quo, as well as their proposed solutions to the problem of sexual violence. Such strategic presentism “offer[s] us new ways to engage with the urgent task of asking how the Victorian era might help us imagine alternative futures” (Coombs and Coriale 88), while still “acknowledg[ing] the alterity of the past” (87). Meredith’s Diana examines the impact of both sexual desire and sexual threat on women’s political, intellectual, and professional ambitions with a sympathetic frankness that aligns it with late-nineteenth-century New Woman fiction.(5) To “be simply a woman’s friend” in a world that reads her claims to independence as invitations for sexual advances is the radical approach to both narration and readership of Diana’s life called upon throughout the novel (Meredith 364). And it remains a radical proposition in a world in which the default interpretation of a woman’s presence remains female sexual availability, as the public non-apologies sparked by #MeToo make clear. From Louis C.K.’s public apology opening, “I said to myself that what I did was O.K.” (C.K.), to Charlie Rose’s statement that “I always felt I was pursuing shared feelings” but was “mistaken,” male “feelings” rhetorically continue to assert predominance over women’s career ambitions and sexual agency (qtd. in Carmon and Brittain). Through insidious turns of phrase, violence, abuses of power, and harassment become merely acts of misinterpretation; predators, merely bad readers.(6) In turn, such “apologies” often portray survivors’ trauma as an equally subjective misreading of intention, rather than an actual abuse that might be objectively measurable in court; Jeffrey Tambor’s statement, which opens with “I am deeply sorry if any action of mine was ever misinterpreted by anyone as being sexually aggressive,” perfectly illustrates this maneuver (qtd. in Wexler and Robbenhol).

<5>Taking this move toward pleading “misinterpretation” on its own terms—rather than dismissing it as only a strategy for deflecting accountability—raises important questions. How do we cultivate a practice of social interpretation that elevates the voices of the most vulnerable, rather than those of the loudest? One that situates consent within tangled threads of circumstance and power rather than in projected desire? The new realism of New Woman novels proves a productive place to look for late-Victorian answers to such questions, because its “authors choose not to view art as a sphere of cultural activity separate from the realm of politics and history” (Ardis 4). If we are to truly “collectively . . . start dismantling these systems that uphold and make space for sexual violence,” following Burke’s call, we must likewise rethink assumptions about the aestheticized separation of how we read texts critically and how we read social situations in the world (qtd. in Murray). In doing so, we must renegotiate space for imagining heterosocial friendship as a social—and narrative—possibility.

<6>Diana of the Crossways positions assault as the logical culmination of cultural assumptions surrounding the relation between the sexes—and understandings of sexuality and power more broadly—even as it attempts to renegotiate both. In this article, I explore the implications of the early nineteenth-century legal practice placed at the crossways of these conflicts in Meredith’s novel: the criminal conversation trial. During such trials, a husband sued his wife’s alleged lover for damages to his property, i.e. his wife. Prior to the 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act, which moved divorce into the realm of civil courts, criminal conversation constituted the second necessary step toward obtaining the individualized Parliamentary bill required for divorce.<7> Like Victorianists today, Meredith turns to the past to work through the questions of heterosocial possibility in his present. Meredith rewrites the explosive scandal that shook the political foundations of Victoria’s reign: the infamous crim con suit, Norton v. Melbourne. Through this re-examination of legal and social modes of interpreting sexual consent and sexual compromise, I argue, Meredith at once renders predation an issue of readership, in the court and in the court of public opinion. Most importantly, for the contemporary reader, he locates a speculative solution in legitimizing heterosocial friendship as a possible narrative relation in itself, and in doing so, teaches us to cultivate a vital critical practice of reading for consent.

(De)Criminalizing Conversation in Norton v. Melbourne

<7>In 1836, George Norton sued Lord Melbourne, Queen Victoria’s first Prime Minister, for criminal conversation with his wife, Caroline Sheridan Norton. George had previously requested that Caroline use her Whig family’s political connections to secure him a magisterial appointment from Melbourne. In the process of achieving this aim, Caroline developed a deep personal friendship with the Prime Minister, and the two engaged in long hours of political and intellectual discussion during his almost daily visits. Those gathered at the criminal conversation trial were exhorted by George’s lawyer, William Follett, “first, to ask themselves ‘what must be the meaning of the visits of Lord Melbourne to this young and beautiful woman’” (qtd. in Craig 79). The question, like the exhortation, proved rhetorical; the court, Follett implied, could not fail to conclude that friendship between “even the best of men” and “a young and beautiful woman” was naturally impossible. As Follett remarked, rather than making it “necessary to prove the direct act of adultery,” such judgments regarding conduct relied on unstable circumstantial evidence such as “the state of general manners, and … many other incidental circumstances apparently slight and delicate in themselves” (qtd. in Atkinson 8). Previous scholarly studies of criminal conversation tend to take the circumstantial assumptions recorded in these historical cases as irrefutable fact.(8) In doing so, they likewise equate the practice with the purpose of the trials and interpret the phrase as a euphemism for confirmed adultery. In many cases, however, such loose requirements for “incidental circumstance” entailed literally criminalizing frequent conversation between a woman and a man not her husband. Much speculation at the time linked Norton’s suit to a Tory maneuvering against the Whig government. Given these concerns, the jury decided the case so firmly in favor of Melbourne’s innocence that they didn’t leave the box to deliberate further on the presented evidence.

<8>Beyond this overt tie between personal scandal and national politics, Norton v. Melbourne proved an exceptional instance of criminal conversation—one that, as Randall Craig notes in The Narratives of Caroline Norton, remained an integral incident in Victorian literary consciousness long after the legal practice itself had disappeared from the courtroom. The majority of these Norton-inspired narratives—from the comic satires of Gilbert and Sullivan to Thackeray’s The Newcomes—not only focus on the tableaux of the courtroom scene itself, but also crucially conflate the crim con trial with confirmed adulterous acts, despite the legal exoneration of Melbourne.

<9>The jury’s declaration of Melbourne’s innocence, it is important to note, did not extend to an equal acquittal of Caroline’s conduct from accusations of sexual promiscuity. Indeed, as the verdict was announced, a member of the jury saw fit to attach the caveat that although “Melbourne had more opportunities than any man ever had before, . . . [he had] made no use of them” (qtd. in Horstman 43). Meredith’s fictionalization of the trial as Warwick v. Dannisburgh nearly five decades later dramatically reframes Caroline Norton’s cultural legacy. By turning away from the rehearsal of accusation and adulterous scandal in the courtroom and instead re-centering Caroline Norton’s searing published self-defenses, Meredith explores, and actively critiques, the interpretative practice—lingering in social speculation long after legal reform—of conflating female publicity and female sexual availability. In doing so, he uniquely decriminalizes conversation between the sexes. Through his exploration of the violence enacted by the cultural logics of marriage and domesticity, I argue, he also reconfigures existing nineteenth-century frameworks for reading consent and predation.

“Canine Under Its Polish”: The Violence and Violation of ‘Civil’ Interpretation

<10>Throughout Diana, Meredith indicts the civility of a social world “still canine under its polish” (8). The canine, for Meredith, lies in the practice of reading female sociality beyond the domestic as, at best, an invitation to sexual speculation and, at worst, an incitement to sexual violence. Indeed, Meredith’s narrator repeatedly blurs the line between reading for criminal conversation and reading for criminal assault. As Carolyn Conley has found, conversational exchange or prior acquaintance with the perpetrator was also frequently equated with sexual consent in rape trials of the period (and far beyond).(9) Meredith likewise intricately interweaves the two legal contexts for determining the extent of a woman’s sexual willingness. Throughout the narrative, he deploys the same critique against the so-called “civilized” instinct to misread the merely social as sexual as he does against the provincial logics of “the famous ancestral pleas of ‘the passion for his charmer’” employed to excuse more overt violence (Meredith 43). Both ways of reading female behavior as assent to sexual compromise, he notes with a startlingly modern insight, have little to do with sexuality, and everything to do with a calculated imposition of punishment against female pretensions to liberty. With regard to the criminal conversation case of Warwick v. Dannisburgh, he writes: “Mrs. Warwick had numerous apologists. Those trusting her perfect rectitude were rarer. The liberty she allowed herself in speech and action must have been trying to her defenders in a land like ours” (7), a land in which public sympathy weaponizes codes of conduct and “depend[s] on the women being discreet, the men civilized” (43). As Meredith later notes while describing Lady Dunstane’s realization that Diana has suffered an assault at a party, this land also interprets the social indiscretion of beautiful women as their “coy expectation of violent effects upon [men’s] boiling blood” (43). However, Lady Dunstane, Meredith declares, “knew a little of the upper social world of her time” (44), enough to know that the excuse of “‘passion for the charmer’ is an instinct to pull down the standard of the sex, by a bully imposition of sheer physical ascendancy, whenever they see it flying with an air of gallant independence” (44). In other words, rather than a crime of passion expected and perhaps even desired by women who dare to leave their homes or converse freely among men within them, Lady Dunstane reads in her friend’s “persecution” an act of violent warfare against the “standard” of female “independence” (43).

<11>Meredith thus renders the battle of the sexes—a motif frequently invoked throughout Diana—a warfare over the proper principles of interpretation, in the civil courts and the “civilized” society beyond. He places at the center of this interpretative contestation the question of innocence, in its array of entangled legal, sexual, and moral senses. “The world is hostile to the face of an innocence not conventionally simpering and quite surprised; the world prefers decorum to honesty,” he declares, but neither Diana’s intellectual or worldly knowingness nor her active participation in the public realm of political discussion can alter the plain fact of her innocence (99). Like Thomas Hardy’s declaration of the purity of his violated protagonist Tess of the D’Urbervilles six years later, Meredith’s defense of Diana revolves around her enduring purity, asserted through heavy-handed invocations of her namesake, “the divine Huntress” and inviolate goddess of chastity (67). Like Tess as well, Diana’s sexual purity becomes forcibly divorced from the word’s more literal resonances. Purity, in such usage, no longer denotes matters of circumstantial tangibility or reputation, but rather becomes redefined as an unalienable attribute of mental life. In other words, Meredith mandates that Diana’s contested innocence be interpreted by the reader as purely a matter of her individual intentions, rather than a socially-delimited issue of conduct or circumstance.

“Against Her Will”: The Predation of Suspicion

<12>Meredith thus intertwines the defense of Diana’s innocence from a false accusation of criminal conversation with a self-possessed intellectual purity that withstands numerous sexual assaults. In doing so, he undermines earlier social assumptions regarding the inherent promiscuity of conversation between the sexes by juxtaposing such assumptions with evolving late-Victorian notions of affirmative consent. Throughout the century, Martin Wiener argues, “the very notion of consent moved from the negative” definition—one that demanded evidence of physical violence beyond the sexual to suggest a woman’s “strongest possible resistance”—to “the more positive” definition of “explicit assent” (89). Indeed, Wiener marks the 1880s as the decade in which “the formal term ‘without her consent’ gained prominence” over “the term that had been more commonly used, ‘against her will’” (89). In light of this “narrowing of the notion of a woman’s consent to sexual relations,” Meredith’s elevation of Diana’s pure intent over her assumed sexual availability aligns social interpretations of sexual compromise with predatory logics (Wiener 92). Indeed Lady Dunstane, in “recall[ing] [Diana’s] looks, her words, every fleeting gesture” toward her elderly friend Lord Dannisburgh, finds evidence of “nothing but the loveliest freakish innocence in Diana’s conduct,” and recasts the sexualized speculations that surround their interactions as “unmanly,” “unworthy,” (70-71) and “vile suspicions” (75).

<13>Previously in Meredith’s narrative, this same suspicious reading that interprets a friendly ramble in the woods as implicit sexual invitation culminates in a literal act of predation. During just such a wooded walk, Lady Dunstane’s rakish husband, Sir Lukin, attacks Diana:

She remembered long afterward the sweet simpleness of her feelings as she took in the scent of wild flowers along the lanes and entered the wood—jaws of another monstrous and blackening experience. . . . She found her hand seized—her waist. Even then, so impossible is it to conceive the unimaginable even when the apparition of it smites us, she expected some protesting absurdity, or that he had seen something in her path. . . . Her reproachful repulsion of eyes was unmistakable, withering; as masterful as a superior force on his muscles.—What thing had he been taking her for?—She asked it within: and he of himself, in a reflective gasp. . . . The question, was I guilty of any lightness—anything to bring this on me? would not be laid [to rest]. (46-47)

This incident is movingly framed by the clear initial contrast between Diana’s intent and Lukin’s interpretation, as well as the sudden reversal of their positions: “the sweet simpleness of her feelings” (46) jarring against the “unimaginable . . .thing [he] had been taking her for,” then her self-accusation of “light” behavior against “the reflective gasp” of his sudden conception of the violence of his misinterpretation (47). While Sir Lukin’s moment of contrition for seeing in Diana a “thing” proves fleeting—Meredith later underscores his “serenest absence of conscience”—the scene proves pivotal to the unfolding of Diana’s plot (66). Fleeing first from her initial assault into yet another at the friend’s home where she seeks shelter, the homeless Diana flees yet again, seeking protection from further attempts in a patriarchal marriage that promises cover. In seeking marital protection, however, she runs right into the devouring jaws of British coverture law, famously figured by the feminist campaigner Frances Power Cobbe as a “Tarantula Spider” who “gobbles up” his mate whole (123). Any protection from violence in public thus comes at the price of accepting violence at home, and, as Diana laments, the battle of the sexes continues on yet another front: “we walked a dozen steps in stupefied union, and hit upon a crossways. . . . By resisting, I made him a tyrant and he, by insisting, made me a rebel” (131).

<14>At stake in Diana’s plea for “simply a friend,” then, was the release of women from a sexual contract in which impoverished freedom brings traumatic sexual vulnerability, but marriage only serves to confirm a legalized absence of sexual autonomy. Such a plea might thus be read as the desire for a ceasefire from the gendered violence legitimized and perpetuated by the law itself—a violence that, as many readings of the Norton trial have noted, proved a much more effective weapon at the disposal of British husbands in silencing their wives than physical abuse.(10) While on trial for adulterous conduct, wives were not a party to the criminal conversation suit and were excluded from testifying. Within such narrative frameworks, the accused woman becomes an object of sexualized interpretative constructions rather than a narrative agent, and “she is allowed no voice in the proceedings, although it is her reputation that is always the point in discussion,” as an 1855 article in Household Words notes (“A Legal Fiction” 598). In her own writings regarding the necessity of legal reform, Norton frequently articulated the silencing violence of the laws that, as she phrased it, “made [her] appear a painted prostitute in a Public Court before a jury of Englishmen,” while excluding her from the rights to self-defense (qtd. in Craig 85).(11)

<15>Instead, the courts cited her personal correspondence with Melbourne as evidence, and their readings suggest that suspicious interpretation of the kind condemned as predatory within Meredith’s novel predominated during the trial. Without tangential proof of bodily entanglement, Follett’s defense of George Norton often hinged upon such textual interpretation. The “trivial notes” in question are “not love letters,” but then again, they are not not love letters, he notes winkingly to the jury:

These three notes . . . relate only to his hours of calling on Mrs. Norton, nothing more; but there is something in the style even of these trivial notes to lead at least to something like suspicion…. They seem to import much more than the mere words convey. They are written cautiously I admit—there is no profession of love in them, they are not love letters, but they are not written in the ordinary style of correspondence. (qtd. in Craig 86)

In an extraordinary sleight of hand, Follett admits “there is no profession of love in” the letters, but even this absence serves only as evidence of “caution” and grounds for further “suspicion.” In her absence, Caroline’s written words might have spoken for her, and yet Follett’s interpretation further erases her voice from the proceedings, urging others to read beyond what her “mere words convey.”(12) Style becomes suggestive of sex, even as words spell innocence.

<16>Charles Dickens, present in the courtroom as a journalist, described the process through which the proceedings arrived at this mode of reading thus:

There was a tittering when prosecuting counsel tried to ascertain how much thigh Caroline had exposed during one of Melbourne’s visits. There was an altogether more raucous reaction when it was suggested, by one servant, that his Lordship ‘invariably went in’ by the ‘passage behind.’ Supposed love letters were read out, most of which confirmed little more than a mutual liking for piebald ponies and beechwood nuts. (qtd. in Ward 29)

Dickens’s report not only portrays a scene of sexual spectacle in which fragments of the absent Caroline’s body serve as public entertainment, but also an audience primed to read the descriptive in terms of sexual innuendo. In this account, the mundane becomes salacious, until the passage culminates in a skeptical “supposed” that reverses this process. Love returns to “mutual liking,” naked thighs and “back passages” to innocuous small talk of common ground, a process which Meredith’s novel continues.

Predatory Reading

<17>Crucially, Meredith’s novel exports such leering, penetrating gazes from the juries of courtroom spectacle into those of the reading public. Just as Norton’s body disappears from the legal scene only to reappear more visibly as the object of prolonged scrutiny in the scandal newspapers, reproductions of Diana’s body and speculations regarding its sexual exploits circulate from hand to hand, “swept from mouth to mouth of the scandalmongers” (Meredith 70). Where Meredith’s narrator declares every crowd she encounters “a jury of some hundreds,” Diana finds the perpetual navigation of such legalized modes of social evaluation unbearable (127). “I cannot face the world,” she laments, “In the dock, yes. Not where I am expected to smile and sparkle, on pain of incurring suspicion if I show a sign of oppression” (Meredith 71). By nature of her exclusion from verbal testimony, Diana’s body, her behavior, her expressions are rendered prey to suspicious readings that transmute natural human reactions into admissions of sexual transgression.

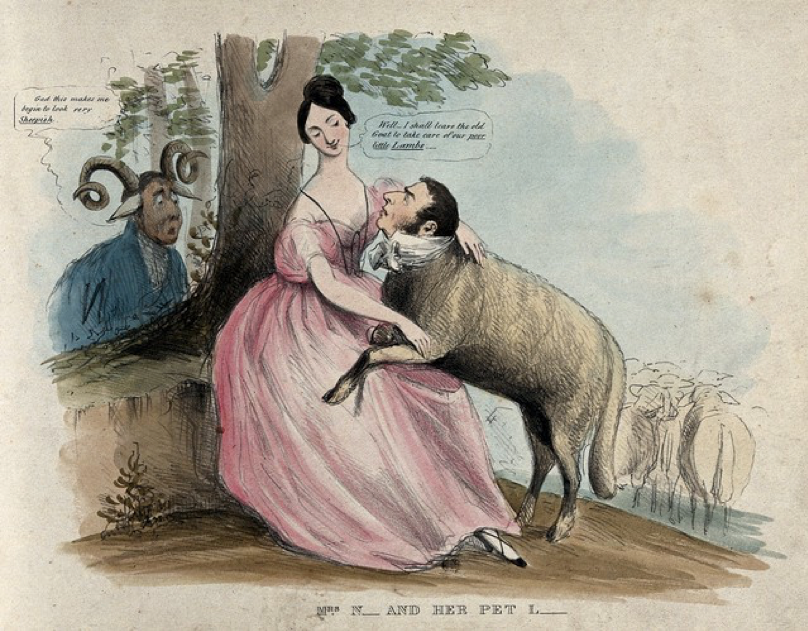

<18>In his novel, Meredith disseminates these modes of interpretative judgment from the legal scene through the popular press to the public. As Judith Rowbotham and Kim Stevenson have noted, Victorian print culture and “press conversation” surrounding criminal trials played a crucial role in “maintain[ing] popular consent to the operation of the legal system,” cultivating a “sociocultural spirit of agreement” (xxiii). Meredith’s narrative renders this “spirit of agreement” an act of “popular consent” rooted in predatory instinct that itself enacts sexualized violence against the object of its study: “That cry of hounds at her disrobing by Law is instinctive,” he writes, “She runs, and they give tongue; she is a creature of the chase. Let her escape unmangled, it will pass in the record that she did once publicly run” (Meredith 7). This law of popular opinion and public “disrobing” of reputation through circumstantial evidence becomes, in Meredith’s formulation, metonymic with the hunt, with, as he puts it elsewhere, “a luxurious roll in the carrion . . . a revival of original instincts” (69). A popular motif of sexual and domestic violence throughout—and even prior to—the eighteenth century, the violence of the chase, the hunt, and the pursuit of prey were commonly linked to feminist challenges to women’s exclusion from Cartesian subjectivity and political sovereignty.(13) Here, however, Meredith appropriates this imagery and its cultural resonances to challenge problematic modes of legal and social readership linked to such systemic violations of female agency. Inverting the exaggerated sexuality of the ensnaring female preying on the docile lamb depicted in print culture caricatures of crim con, Meredith gives us instead a masculinized instinct that pervades the predatory social body bent on the public violation of a scapegoat (see figure 1).

<19>Meredith further cements this connection between the pursuit of prey through the woods and the popular reveling in the printed exposure of the body marked by scandal. Tellingly, he chooses Diana’s assailant, Sir Lukin, as the representative of both: “He of his nature belonged to the hunting pack, and with a cordial feeling for the quarry, he was quite with his world in expecting to see her run, and readiness to join the chase. . . . and he, too, with a very cordial feeling for the quarry, piously hoping she would escape, already had his nose to the ground, collecting testimony in the track of her” (63-64). Meredith aligns these modes of social reading for “evidence” with a pervasive sexual and textual predation that finds pleasure in both rewriting the traumatic spectacle as consumable scandal and reading in scandal itself the sexual availability of its object.

<20>Importantly, too, Meredith constructs this predatory pursuit as a collective interpretative practice. Rather than the singular, sexually aggressive villain from which the sexually vulnerable innocent can be saved, Lukin stands “quite with his world.” This quiet admonition uniquely moves away from melodrama, the primary genre in which Victorian sexual violence appeared as a plot convention, and toward a radical realism that acknowledges the interplay of individual action and social environment in such events. In her own writings about her experience with divorce and child custody law, Caroline Norton wrote within melodramatic conventions of the moustache-twirling villain and his powerless victim, male aggression and female dependence. As Mary Poovey has argued, Norton, by necessity, operated strategically within this style to garner her audience’s sympathies as a woman unorthodoxly speaking out against her husband in public discourse. To do so, she needed to situate her story within well-known cultural logics, including “the sexual double standard”: “if male sexuality were not aggressive and predatory, after all, and if females were not innocent, vulnerable, and valuable precisely in this vulnerable innocence, villainy would assume a different guise and plots would not tell of innocence persecuted and then saved” (Poovey 83). Lukin, for all his faults, remains a complex character rather than a cartoon villain; he lives within an eerily recognizable cognitive dissonance that allows him, by turns, to easily forget his acts of sexual aggression and to rationalize them as not that bad.

<21>By aligning Lukin’s predatory logics with those of his social world, the novel dresses its villainy in the “different guise” of what we might now term rape culture. And in the narratives—realist and real—written within its terms, persecution is rarely followed by salvation. The circulation of scandal under the interpretative gaze of the reading public often has functioned as the paradoxical grounds upon which victims’ lack of sexual interest and their credibility is questioned. In 1991, senators accused Anita Hill of “imagin[ing] or fantasiz[ing]” about the very harassment of which she accused Clarence Thomas, and as Rebecca Solnit has noted, this “Freudian framework” of unconscious sexual desire—“when she said something repellant had happened, she was wishing it had”—still follows survivors who come forward with their trauma (111). Over two decades later, the enraged tears of an entitled man upheld and the measured words of another woman dismissed remain indelible in the hippocampus, and less high-profile survivors who came forward in the wake of #MeToo have not fared much better.(14) Many of these women still lack employment, “their names quickly forgotten—until a prospective employer Googles them,” and “the same public that has used their stories …[for] headline-grabbing” remains resoundingly indifferent (Traister). In this light, Meredith’s prediction rings utterly true: “it will pass in the record that she did once publicly run,” and the very act of reporting unwanted sexual advances will make her sexually and morally suspect (Meredith 7).

“With the Eyes of a Friend”

<22>If Meredith frames the female casualties of this battle between the sexes as victims of interpretation gone awry, he also frames the possibility of the conflict’s resolution as a matter of cultivating an alternative form of readership through the character of Redworth. Primarily depicted throughout the novel as the “true friend of women” (77), Redworth turns away from the cultural codes of conduct and circumstance that compel others to read Diana as “a creature of the wilds, marked for our ancient running” . . . “to look” instead “at her with the eyes of a friend” (89). If “it is the test of the civilized to see and hear, and add no yapping to the spectacle,” as Meredith exhorts his male readers to do in the opening chapter of Diana, such exhortations toward heterosocial possibility take a radical interpretative stance (7). Despite the novel’s consciousness throughout of Diana’s intersecting vulnerabilities as an Irish working-class woman, this stance remains limited by the imperialist reverberations in his frequent employment of the language of civilization and primitivity—a limitation likely directly derived from his affiliation with early feminism itself. In rendering sexual and subsequent social violations an issue of readership, however, Meredith productively prompts us to move beyond the legal and social frameworks for interpreting consent as circumstantially plotted and predetermined—as always already given—even as he unintentionally prompts us toward intersectionality in our cultivation of new frameworks. In Diana, Meredith gives us a female protagonist with an astonishing complexity of social relationships; she emerges as a fully realized human being who might experience sexual desire for one person without being sexually interested in everyone at all times and who equally desires human connection of other kinds. This complexity has much to teach contemporary culture, which still has difficulty conceptualizing sexual desire and consent so dynamically.(15)

<23>What, then, might it mean to read the acts of nineteenth-century women “with the eyes of a friend,” with a belief that surpasses critical suspicion? Although Redworth remains secretly in love with Diana throughout the novel, the friendly interpretation Meredith holds up as a model for his own readers requires the active suppression of his lover’s “jealousy,” which initially prompts “the question” of her indiscretion to “bite . . . [at] his nerves” (89). Rather than a projection of sexual desires, then, to read “with the eyes of a friend,” Meredith’s description suggests, requires a “power of faith” in a woman’s assertions, a “pity” for her circumstances, and a full knowledge of her character in the face of the cultural “doubt [that] casts her forth, the general yelp [that] drags her down” (89). Even—and most especially—when Redworth’s temporary doubts indict him in his “strong resemblance to his fellowmen,” such reading closely resembles Burke’s call for an empathetic understanding, accountability, and healing that continues to elude us in this moment (89).

<24>Friendship has long been critically aligned with consensual feeling, democratic structures, and mutual equality, but rarely has attention been paid to the important ideological role that friendly social bonds between unmarried men and women might play in nineteenth-century fiction.(16) Victorian criticism’s decentering of heterosocial friendship stems from the historical rise of separate spheres ideology, but also our deeply embedded assumptions regarding the predominance of sexual desire in driving social and narrative forms.(17) Reading the novel, the Victorian novel in particular, has been tied again and again to uncovering its masked, liberatory erotics.(18) In the aftermath of Stephen Marcus’s The Other Victorians and Foucault’s subsequent articulation of the repressive hypothesis in The History of Sexuality, studies of the hidden desires and secret pleasures that lie beneath the novel’s denials have proliferated and dispelled myths of Victorian prudishness. But alongside rich historical archives, this tradition of reading literary texts has also equated silence with sexual feeling, absence with mere respectability, and even female rejection or denial of male advances as coy sexual availability.(19)

<25>More recently, scholars such as Sharon Marcus and Talia Schaffer have multiplied our critical practices for reading female agency, as well as our critical vocabularies for the web of social relations that exist beyond the structures of heterosexual desire. So too have many prominent critics since challenged the effectiveness of separate spheres ideology as an interpretative framework for reading social relations in the period—calling attention to the “uneven developments” of its cultural logics (Poovey passim) and the “play” that women found “within [its] system[s]” (Marcus 27).

<26>Yet little attention has been paid to sites of overlap in which heterosocial friendship outside of marriage—or even the desire for it—was cultivated and expressed. This indicates a more embedded obstacle to theorizing friendship’s role in literary form and critical reading: as Victor Luftig has noted, “contemporary phrasings, like their predecessors in earlier time, define male/female friendship according to what it is not[:] ‘Just friends,’ ‘only friends,’ ‘not lovers,’ and similar combinations” (1). In other words, we read in it a lack, where in fact there lies a very vibrant and rich presence. Alongside continued explorations of the various sexualities that drive Victorian narratives, then, it is particularly vital in this moment to continue to clear space for theorizing heterosocial friendship as a form and a feeling in its own right crucial to these narratives.

<27>Of equal importance, doing so requires critical practices newly attentive to the real social politics of the ways in which we read female figures—their thoughts and their assertions—within these texts. Meredith’s alignment of predatory and suspicious readings might also prompt us to follow Rita Felski’s call in The Limits of Critique to question our deeply held assumptions about the “intrinsic” alliance of critique and radicalism, to be more reflective about the ways we engage with the dynamics of interpretative practice (6). Like Meredith, Felski recognizes suspicion as something “thoroughly enmeshed in the world rather than opposed to the world,” and asserts that it “offers no special guarantee of intellectual insight, political virtue, or ideological purity” (51). Might we then begin to consider the ways in which reading suspiciously for sexual interest and pleasure in silences and rejections can be used to reinforce the culturally embedded logics of sexual predation, just as it can be deployed to lend expression to radical forms of sexual agency?

<28>In the wake of Franco Moretti, Simon Jarvis, Jay Fliegelman, Avital Ronell, and countless others, we, as academics, must face the fact that there is nothing inherent in what we do that comes with an immunity to problems of sexual violence and the exploitation of power. In fact, as Caroline Fredrickson has noted, “academia is particularly fertile territory for those who want to leverage their power to gain sexual favors or inflict sexual violence on vulnerable individuals.” In this light, it’s especially important to consider the ways in which modes of critical and epistemological reading uncomfortably reflect these problematic dynamics. Assuming that words don’t always mean exactly (or only) what they mean on the surface is both critically useful and fundamentally flawed from a contemporary consent framework. What could be more paranoid, in Eve Sedgwick’s sense of the word, than complex theories of rape culture? But then again, what phrase could jar more completely against the hermeneutics of suspicion than “no means no and yes means yes”? I do not mean to suggest that we should reject this interpretative tool that has been indispensable to humanistic inquiry, or even that “no means no” constitutes the most complex framework for theorizing consent in practice, given the entrenched power imbalances at the heart of this issue.

<29>However, I do suggest that our current deployment of interpretative suspicion—reading against the surface for buried sexual connection or asserting the predominance of ideological norms—tends to favor abusers. In The Stanford Daily’s report on the assault allegations against Moretti, an interviewee, “a friendly ‘acquaintance’ rather than a friend” of one survivor, remarked that “my sense of things is that Moretti had a very different idea of what was going on” and went on to explain the normalization of professor-student relationships back in the day (qtd. in Liu and Knowles). Oddly enough, though, these students reported the incidents as assault and harassment back in that very same day, a detail not to be explained away by speculations about their attacker’s interiority or explanations of cultural norms. These frameworks of “misinterpretation” or “different idea[s]” only make sense as justifications if you’re taking predatory interpretation as the default. Indeed, predators and their defenders employ this slanted version of critique’s logics almost as frequently as their behavior lies visible right on the surface, there for all who were looking to see. Such moments of collision, I suggest, require a moment of reckoning akin to Meredith’s evocative description of Diana and Lukin’s walk into the dark woods, where claims to “misinterpretation” demand a true reevaluation of one’s interpretative principles. A practice friendly to reading consent mandates that the “thing [he] had been taking her for” be seen as a complex being, both full of individual will and independent desires and enmeshed in systems of power that too often limit their expression (Meredith 47). We must reflect on the ways in which we’ve been taught to see through denials of sexual interest, but to take predators’ denials of sexual misconduct at face value; to glance past expressed female interiority in the suspicion of buried erotic desire, but to delve into deep speculations about men’s innocent intentions. At the crossways of the academic reading debates, in our own time of instability and reckoning, our work demands such reflections.

Acknowledgements

This article emerged from a paper delivered at the 2019 Indiana University Interdisciplinary Graduate Conference, “Reckoning with Consent and Contract in Times of Instability.” Many thanks to my dissertation chair, Monique Morgan, for her encouragement and helpful feedback at every stage of my ideas. Thank you, as well, to the conference organizers, Christie Debelius and Chelsey Moler Ford, and the other panel participants for the insightful conversations that took place.