<1>Midway through my first semester of emergency remote teaching, I began to dread the Canvas discussion board. As my institution—a small, Franciscan liberal arts college just outside of Albany, New York—pivoted to emergency remote instruction in March 2020, I decided to offer a range of synchronous and asynchronous engagement options for students depending on their specific needs. As COVID-19 ravaged New York State, some students—in search of community, structure, or routine—opted to join live classes, while others—in need of flexibility due to work schedules, caregiving responsibilities, or illnesses—chose to engage asynchronously.

<2>My earliest asynchronous activities consisted of traditional discussion board questions that strike me now as rather cringeworthy—woefully unimaginative and unnecessarily demanding. When my upper-level Victorian literature students read excerpts from T. N. Mukharji’s A Visit to Europe (1889) and Pandita Ramabai Sarasvati’s The High-Caste Hindu Woman (1887), for instance, I posted the following prompt: “How do Mukharji and Sarasvati depict colonialism in their works? Please point to at least one passage from each work in your discussion. Your response should be approx. one paragraph.” In other posts, I gave instructions like “write two to three sentences about X,” “please answer at least one of the three following questions,” or “please respond to at least two of your classmates’ posts.” Such prompts left little space for student creativity and exploration.

<3>My students answered these questions diligently and thoughtfully, putting great care into their posts and often penning lengthy responses to their peers’ ideas. But after several weeks, students began to admit to me that they were experiencing massive discussion board fatigue. Between all of their classes—most of our students take five or six courses a semester—they had so many posts to complete, so many words to write, so many tasks to accomplish. One student joked with me that they “live[d] on Canvas now.” By the end of the semester, I, too, had to will myself to log onto Canvas to comment on posts.

<4>A foray into digital pedagogy scholarship revealed that I was not alone in my frustration with the LMS discussion board, and I began to recognize that my rather uninspired and uncritical approach to the medium had contributed to the weariness my students and I were experiencing. As Sean Michael Morris and Jesse Stommel write,

Instead of providing fertile ground for brilliant and lively conversation, discussion forums are allowed to go to seed. They become over-cultivated factory farms, in which nothing unexpected or original is permitted to flourish . . . At their worst, discussion forums are less like classrooms and more like bus stops—each participant stopping by, saying a few words, and then going on their way. (84-85, 87)

My discussion board questions had become such tiresome “bus stops” or “factory farms”—rule-bound and inflexible in ways that stifled conversation and deadened engagement, representing just another “task” on my students’ (and my own) already interminable to-do lists.

Searching for Something New

<5>Over the summer, I began to research ways to, as Stommel and Morris suggest, “hack” the LMS discussion boards “mercilessly” (84). Several scholars have offered models for how to better facilitate engagement on such forums. John Orlando suggests replacing the stiff “post once, respond twice” model with invitations for students to post “one or two original thoughts.” As Orlando writes, this practice opens up the possibility that “a response to someone else’s point might contain more insight and creativity than an original posting.” Morton Ann Gernsbacher proposes dividing “any class larger than a dozen students into subsections of six to eight students and creat[ing] a separate but parallel discussion board for each subsection” to better foster “interaction and engagement.” Flower Darby and James Lang emphasize the need for frequent instructor feedback in order to promote a lively discussion board atmosphere (86-87). In this issue, Carrie Dickison discusses how a Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework can help students and instructors shift from a “content delivery” model to one that centers the “collaborative creation of new knowledge.” Morris and Stommel suggest supplementing or merging discussion forums with other tools such as Disqus, Twitter, Vanilla Forums, Facebook, or Wordpress (87-89). Flexibility with discussion tools, they write, can “actively open the world to the student, without dashing her upon its rocks, rather than box her in (technologically, pedagogically)” (87-89).

<6>With these suggestions in mind, I began to try out new tactics for asynchronous engagement in my Fall 2020 classes—one fully online, the other two HyFlex(1)—to varying degrees of success. At one point, I excitedly showed students how to use VoiceThread, a tool that integrates with Canvas to allow for video or audio comments, and explained that they could submit oral rather than written responses to discussion questions—an option that not one student took the entire semester (an outcome that I will have to ponder further). A bit more successful were prompts that invited students to make memes or GIFs about Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847), which resulted in hilarious commentary about Rochester’s “weird dog” and St. John’s “desert missionary proposal” (“#sotempting”). Students also responded well to invitations to contribute to shared Google Docs to make lists (such as “What makes us human?” as we read Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go [2005]) or collaboratively annotate poems or short passages, such as the first sentences of Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987). Students commented that they liked these kinds of collaborative activities because it made them feel as though they were “reading together.”

<7>Yet, as the semester progressed, I still found myself looking for more ways to encourage enthusiasm and engagement in low-stakes contexts. Google Docs were great, but I found that they seemed to compel students to generate more formal or polished writing than I expected in these short exercises; I suspected that this was in part because Google Docs are also the medium in which most of them compose their formal essays. I also felt that group annotation activities using Google Docs’s “Comments” feature too easily devolved into the “bus stop” model I had been trying to avoid on the Canvas discussion boards; I found myself asking students to generate a certain number of annotations on each Doc and, when I realized they weren’t engaging with each other’s comments, a certain number of responses to their peers’ posts.

Learning to Jam

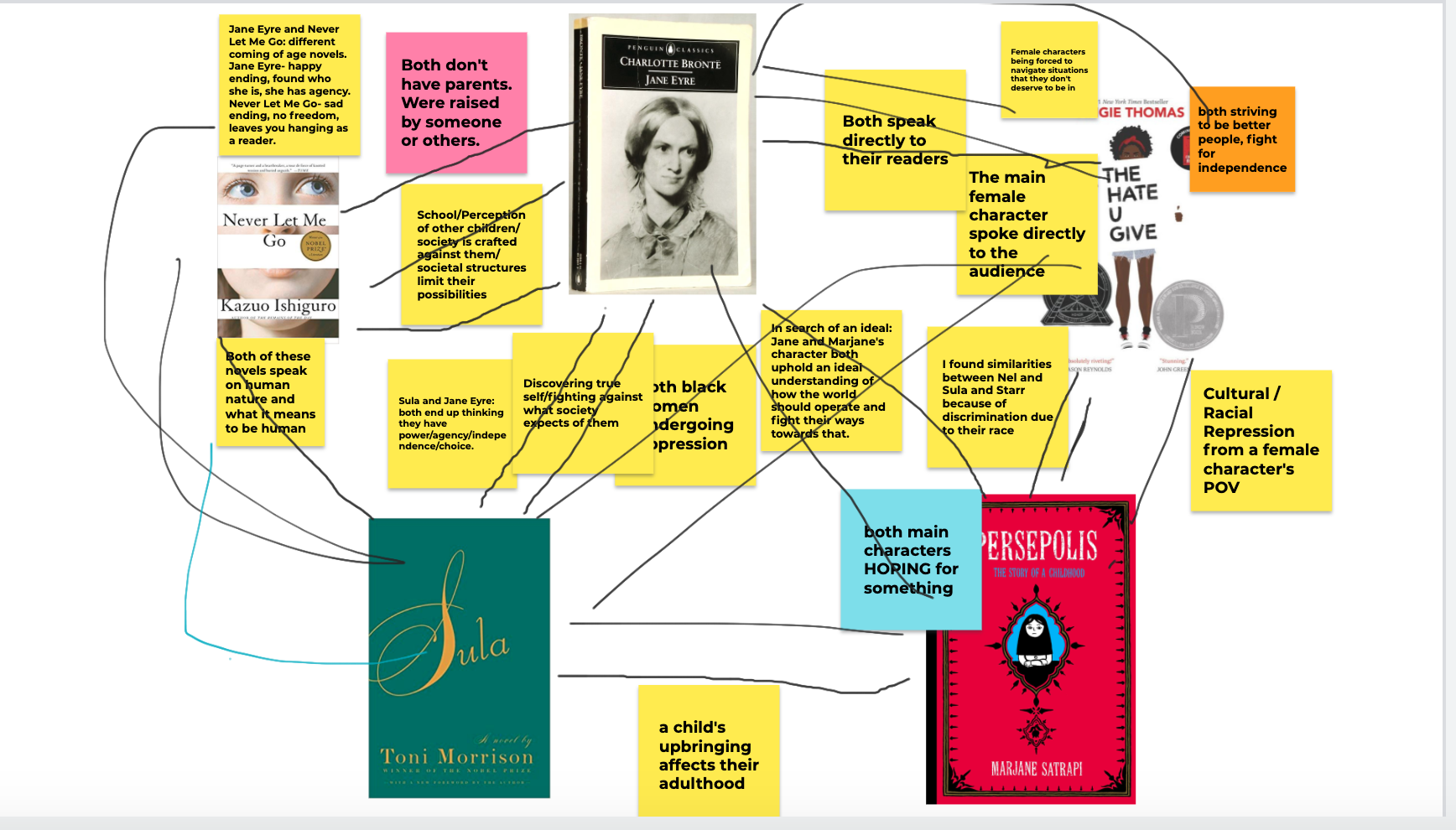

<8>On the very last day of class in Fall 2020, I stumbled across a Twitter thread (though I cannot find it now) about Google Jamboard—a tool that provides a set of virtual whiteboards (“Jams”) to which everyone with the link and editing access can contribute. From what I could tell, Jamboard is often used in business contexts or in early childhood education settings, but I could immediately envision its utility for the virtual college classroom. The timing of my Twitter scroll was fortuitous; I was half an hour away from teaching my final class on The Novel, a class session in which, when in person, I like to tape pictures of the novels we read over the semester on the board and ask students to (literally) draw connections between them with whiteboard markers. I had not yet found a way to digitally replicate this exercise and so was planning to do something else in class. Yet, after finding the tweet about Jamboard and playing around with the tool for a few minutes, I decided to try it out to replicate this final synthesis discussion. After a few hiccups on my part (at first, I forgot to give the students editing access), the students caught on very easily, figuring out (even before I did) how to draw lines between novels with the “highlighter” tool and create “sticky notes” to include short comments (see Fig. 1). What resulted was not only a dynamic conversation about the confluences between our course texts, but also a moment of levity and fun: “This looks so pretty!” one student commented. At a time of intense anxiety for students—marked by rising COVID-19 cases, impending final exams, and looming pandemic holidays—the chance to cover a document with colors and doodles gave us all a few minutes of much-needed mirth.

<9>Since this class session, I have experimented much more extensively with Jamboard in both synchronous and asynchronous settings. Here, I share what I have found to be some of Jamboard’s richest pedagogical affordances. Not only is Jamboard practically useful—it is relatively simple to learn and share—but it also helps me to promote the kinds of engagement I have been seeking in my online classrooms: Jamboard exercises can be casual, collaborative, and fun. They have helped me to embrace a more playful online pedagogy, one that encourages students to experiment, improvise, mess up, collaborate, and share their feelings. This approach helps me to signal my pedagogical priorities: inquiry and exploration over correctness and certainty, flexibility and compassion over exactitude and “rigor.”(2) Moreover, Jamboard’s capacity for anonymous contributions enables me to facilitate safe, inclusive, and low-stakes discussions.(3) Students can engage with the texts at whatever levels they feel most comfortable, without worrying about surveillance or evaluation from me or their peers. Conversations can center on a dynamic (and fun!) exchange of ideas rather than a competitive or anxiety-inducing quest for credit or approval.

<10>I am by no means an expert on—or evangelist for—Jamboard. I’m sure that I have not learned half of the tools that Jamboard offers, and I’m profoundly wary of any tool produced by a giant corporation like Google that already demands (and monetizes) so much of our time and attention. In addition, while Jamboard strikes me as relatively financially accessible—it is free to use and works on computers, tablets, and smartphones (there is a Jamboard app for both iOS and Android devices)—it still needs a lot of work in terms of accessibility to support the tenets of Universal Design for Learning (UDL). According to the Jamboard Help Center’s page “Make Jamboard meetings more accessible,” Jamboard enables TalkBack and gesture navigation on Google screen readers, but only on Google Meets or on Android apps. I also worry that some students might find Jams overstimulating with all of the colors, lines, and text that they enable. Like all tools for remote (or, for that matter, in-person) learning, Jamboard has significant limitations. Rather than hailing Jamboard as a panacea for the remote classroom, my goal here is simply to share a tool that has made the remote classroom a little less stressful, a little more interactive, and a bit more fun—outcomes that, in these times of ongoing crisis, isolation, and trauma, seem more crucial than ever.

How Jamboard Works and How I Use It

<11>I’ll begin by offering a brief overview of how Jamboard works and how I use it in the classroom. First, I visit jamboard.google.com and log in with my Google credentials; Jamboard does require a Google account, which can be created for free, to create (though not to use) a Jam. To create a “New Jam,” I click the orange “+” button at the bottom right hand of the screen. Once I create a Jam, I can add text boxes, sticky notes, and images as well as highlight, underline, or circle content—all found on a toolbar on the left-hand side of the screen (see Fig. 2 below). I can also add new pages to each Jam by clicking the arrows above the frame at the center of the screen. To make the Jam accessible to others as either viewers or editors, I click the blue “Share” button on the top right hand of the screen. I can share the Jam with anyone at my institution or “Anyone with the link”; I find the latter option easier to use in class since it saves students the step of having to login with Google credentials that may not be saved on their computers. Once I select these options, Google generates a link that I can copy and paste into a Zoom chat, Canvas discussion board, or email message. While I can generate Jams in real time during class, I can also set them up ahead of time, a function that saves valuable class time and alleviates my own stress as I prepare.

<12>I have used Jamboard in several teaching contexts. Most simply, I use Jamboard as a whiteboard or projector stand-in during remote, synchronous class sessions. I often add a text box with a literary passage or an image of a poem, screenshotted from a site like Poetry Foundation, and then share my screen with the students so we are all looking at the same “board.” In these instances, I am the “driver” of the Jam; I underline key phrases, create sticky notes or text boxes to jot down student comments, or use the laser pointer function to draw students’ attention to particularly noteworthy words or phrases. Used this way, Jams are not that different from PDFs or Word documents, though I find Jamboard’s annotation tools (especially the laser pointer) much less clunky and easier to use than those in other formats.

<13>However, Jams become much more generative of what bell hooks calls “collective effort” when they are shared (8). By far the most exciting Jams emerge when students become their primary contributors or creators. In such moments, they embrace more active roles in the class and become more engaged members of their “learning community” (hooks 8). My students and I have developed several Jamboard activities for both synchronous and asynchronous discussions, which I outline briefly below.

“Come up and write on the board”

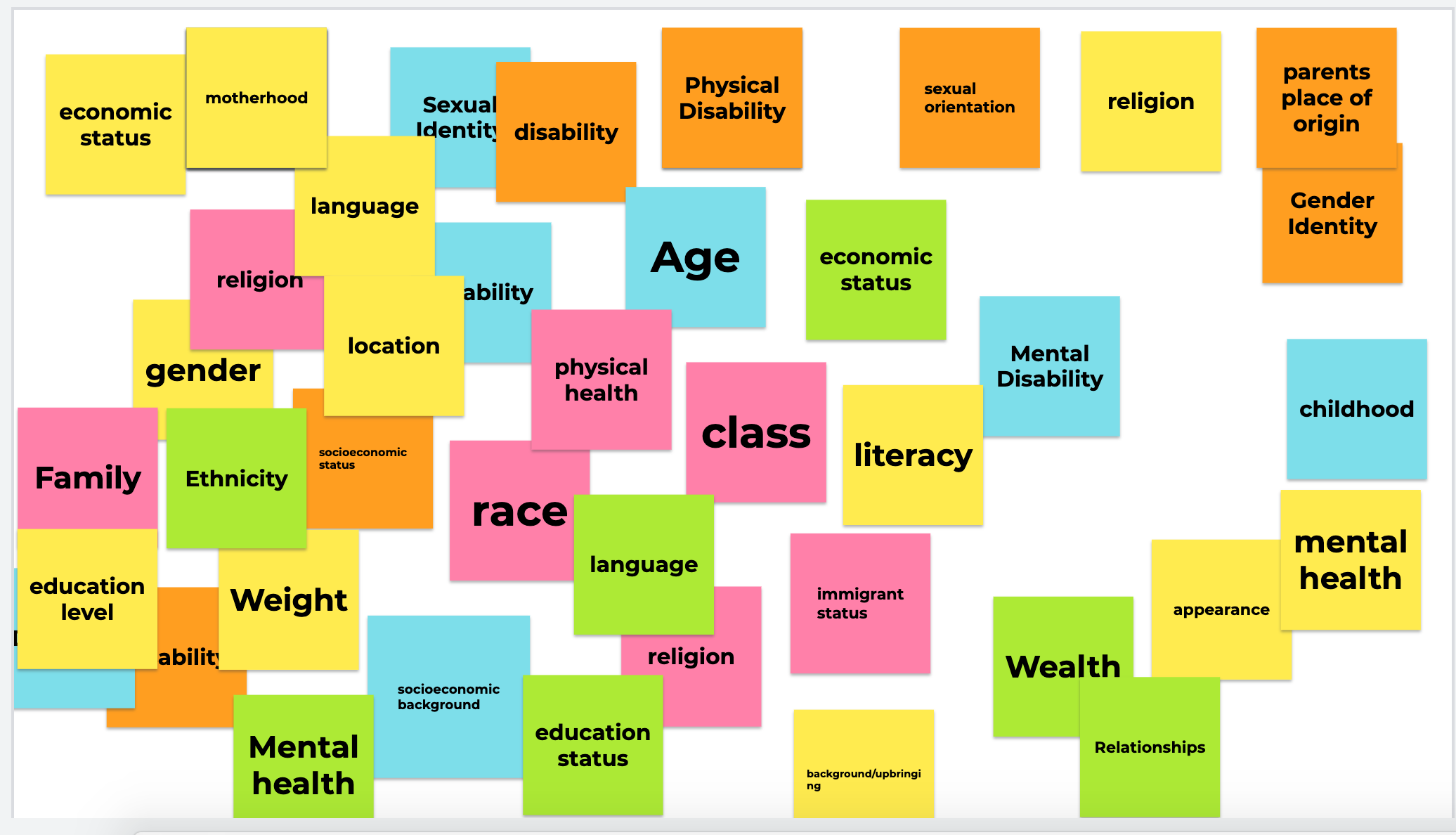

<14>My students and I have found Jamboard particularly useful for in-class brainstorming activities—virtual parallels to in-class moments in which I invite students to “come up and write on the board.” A couple of times, I have asked students to add as many sticky notes to a Jam as they can in a particular amount of time. For instance, when my Spring 2021 Women in Literature students were learning about Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality, I dropped a link to a blank Jam in the Zoom Chat and gave them one minute to add as many intersecting vectors of identity and oppression (e.g., race, class, sexuality) as they could think of (see Fig. 3).

<15>At the end of the exercise, students had collaboratively created an extensive list of vectors—many of which their peers and I had not thought of. The format of the Jam, on which all of the sticky notes overlapped—or rather, intersected—with each other, created an unexpectedly striking visual illustration of Crenshaw’s concept. Similarly, when the same class read Audre Lorde’s “The Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” in which Lorde describes the erotic not as simply base, sexual “sensation without feeling,” but as a life-sustaining “resource” of power, pleasure, and knowledge,(4) I invited students to spend two minutes adding sticky notes to a Jam that reflected things in their own lives that they found to be “erotic” in Lorde’s sense of the term (53-54). What emerged was a vibrant page brimming with colorful sticky notes that reflected what gave them, in Lorde’s terms, the “kind of energy that heightens and sensitizes and strengthens all [their] experience[s]” (57). While such Jamboard exercises lack the kinds of kinesthetic engagement fostered when students move around the classroom and draw on the board, they are more efficient and accessible, allowing everyone to write at the same time (and thus avoiding the awkward marker-sharing dance) and enabling students with mobility issues to participate without having to struggle to move or disclose their needs to everyone. Moreover, as I will discuss in more detail below, the anonymity of Jamboard in this instance meant that students felt safer and more comfortable sharing in such a potentially personal activity. They could see what their classmates had posted and share something intimate, if they wished, without having to “own” their comment or disclose their identity.

Writing Workshops

<16>Jamboard can also help to facilitate collaborative writing exercises. In Introduction to Literature, a lower-level course in which academic writing is a major component, I have used Jamboard to help students practice skills such as crafting thesis statements and topic sentences. Sometimes, I divide students into several Zoom breakout rooms and ask each group to create a working thesis about a course text and add it to a shared Jam. Then, when we come back together, I invite students to scroll through the Jam and annotate each other’s theses, underlining useful points or posing questions or suggestions in the margins. I have also used Jamboard for one-on-one peer review, asking each student to put their working thesis statement onto a Jam and then provide feedback on their classmates’ claims. The visual space of the Jam frame—large enough to accommodate a typed thesis statement as well as lots of peripheral commentary—and Jamboard’s many tools—such as highlighting, underlining, and text insertion—enables forms of peer review that are much more dynamic than those facilitated by Track Changes or the usual pen-and-paper feedback worksheet I hand out in class. Sometimes, I ask students to add bits of their writing to different Jam pages and then give the whole class a chunk of time to read through all of the pages and make comments. In these contexts, in-class writing exercises can feel truly “low-stakes,” allowing students to anonymously share writing about which they might feel embarrassed or vulnerable and give and receive feedback about their work.

Group Annotations

<17>Though there are many excellent collaborative annotation tools out there (including Perusall, COVE, and Hypothes.is, to name a few), I am mindful of cost and eager to limit the number of new tech ecosystems my students have to learn (as my institution already uses Google).(5) I have found Jamboard to be a productive (and again, easy and free) tool for “quick and dirty” collaborative annotations. For such exercises, I put the link to a Jam containing that day’s text either in the Zoom chat (for synchronous virtual sessions) or on the Canvas discussion board (for asynchronous sessions) and invite students to annotate it. At first, I required students to submit a certain number of annotations, though I quickly realized that such instructions could default into the discussion board “bus stop” model. Now, I tell them to simply add as many annotations as they can in a given amount of time or to simply annotate the details that strike or move them. At times, I ask asynchronous participants to initial their annotations so I can give them “credit,” though I have recently moved away from this practice in favor of less rigidity and more anonymity.(6)

<18>In synchronous remote classes, in-class collaborative annotation sessions using Jams facilitate more seamless discussions. When students finish annotating, I share my screen with the now-annotated Jam and simply ask students, “What kinds of things did you underline/highlight/comment on?”—often a much less daunting starting point than something like, “what did you think of this poem?” Moreover, the variety of annotation tools that Jamboard provides allows students to engage with literary texts in whatever ways they find most useful. If a student is moved by a particular word, for instance, they can highlight it. If they want to propose a hypothesis, they can post a sticky note. If they want to draw parallels between two words, they can circle both words using the same color marker. Or, if they are baffled by a specific line, they can simply draw a question mark. If they want to amplify another student’s point, they can star or circle a peer’s annotation (more on this later). In any case, Jams allow students to engage in deeper, more active, and more collaborative ways than they otherwise might if we are all simply looking at the same page in our individual books or staring passively at a shared PDF to which only I have access.(7)

Collaborative Close Readings

<19>One of the most fun exercises on Jamboard is a version of an activity I love to do in class: a take on Danica Savonick’s “Collaborative Close Reading” exercise, in which small groups of students take turns annotating short excerpts from texts before passing them around the room to the next group (“Collaborative Close Reading”).(8) On Jamboard, I divide a poem or a piece of prose onto several Jam slides, with one or two lines per slide, and assign each student a particular slide. Next, I time the students, giving them a certain number of seconds or minutes to fully annotate their slide. When the time is up, instead of passing a paper around the room, students simply scroll to the next slide, which is already covered with annotations from the previous students. As Savonick writes, collaborative close reading helps students move from summary to analysis and amplifies the voices of quieter students who might not be as eager to speak up in larger discussions (“Collaborative Close Reading”). This is no less true on Jamboard, which allows students to vividly see what their classmates noticed and easily add their own annotations, working together to generate insights about a course text.

<20>I have already hinted at several of the broader pedagogical affordances of Jamboard in my descriptions of these exercises—namely, its facilitation of active, collaborative, and low-stakes forms of engagement. Below, I will spell these affordances out more specifically and describe how they resonate with key aims in critical, feminist, radical, and trauma-informed pedagogies.

Messiness

<21>Jamboard encourages students to get messy. The word “Jam” itself suggests a kind of experimental, relaxed, and impromptu mode of engagement. “Jam sessions” among musicians, for instance, are collaborative, communal, and casual affairs that prioritize exploration (“jamming”) over perfection and shared creativity over individual achievement. Canvas discussion boards and Google Docs often propel students to produce formal, edited prose that, as they have admitted to me, can take them hours each night to complete. Jamboard does not require—and in fact inhibits—any kind of polish. Instead, Jamboard invites students to share quick, impressionistic responses and immediate reactions. Jams teem with squiggly lines, overlapping highlights, poorly-drawn stars and circles, and cluttered text boxes. Moreover, the sticky notes on Jamboard have a 171-character limit, which encourages comments that are short, speculative, or fragmentary. While some students at first struggle to generate classwork that feels unpolished, they quickly embrace the chance to make a mess. As trauma-informed pedagogy researcher Karen Costa writes in her recent article “Cameras Be Damned,” “Be willing to experiment. Let it [a synchronous, online class] be messy. The best stuff in life usually is.”

<22>As I have used Jamboard more and more, I have realized that this chance for a more casual form of engagement—this chance for “mess”—actually helps to facilitate more inclusive class conversations. When I invite students to “highlight words that stand out to them” or “circle phrases that seem weird,” the discussions that follow often begin on a more observational or exploratory level. The question “what did you underline?” can be a much less overwhelming—but no less productive—starting point for many students, especially those who are hesitant to share comments that they fear don’t reflect fully-formed thoughts. Encouraging students to create messy Jams also helps me to model forms of scholarly engagement that privilege speculation over certainty, complexity over correctness, and experimentation over conclusiveness in ways that resonate with the kinds of epistemological multiplicity, flexibility, and generosity that scholars such as Pardis Dabashi have argued that literary study desperately needs (953-54).

Inclusivity

<23>Largely due to its anonymity, Jamboard enables students to engage at a variety of levels with the course material. If a student is struggling with a particular text, they can simply underline a word or phrase and pose a question—or even just sketch a question mark. If they are especially short on time or intellectually uninspired one day, they can focus their efforts on highlighting key phrases or providing definitions (rather than extensive interpretations) of difficult words—an equally important step in literary analysis. On the other hand, if a student is particularly energized by a poem or passage, they can annotate it to their heart’s content. The anonymity also sets students up for a range of levels of engagement in synchronous sessions. If a student is particularly proud of a comment they made or especially eager to share an idea, they can speak up. Or, if a student wants to speak but is less comfortable sharing an original idea, they can raise their hand to amplify another student’s annotation (“I really liked the sticky note about . . .”). Even if a student never speaks out loud, they still feel as if they have engaged with the material.

Safety

<24>The anonymity of Jamboard also fosters a safer space for potentially difficult or awkward conversations, as when my students shared what they found “erotic” in Lorde’s sense of the term by adding sticky notes to a Jam. When my classes discuss Lorde’s essay in person, students are often reluctant to share; though we discuss how, for Lorde, the “erotic” is different from the “sexual,” students’ associations with the erotic-as-sexual are often so deeply ingrained that they find it embarrassing to discuss publicly. When I ask what students find “erotic” in person, only a few students share. Yet, when we did this as a Jamboard activity, the ten students added over thirty responses to the Jam. Even more surprisingly, perhaps, in the group discussion that followed, almost every student shared verbally what they had added to the Jam. I suspect that seeing the wide array of responses on the Jam and learning what other students found “erotic” may have made many students feel less vulnerable sharing their own contributions. For this reason, I will continue to use Jamboard for such exercises in the in-person classroom. I can imagine inviting students to add sticky notes to the Jam from their laptops or phones (if available) at their desks.

Collaboration

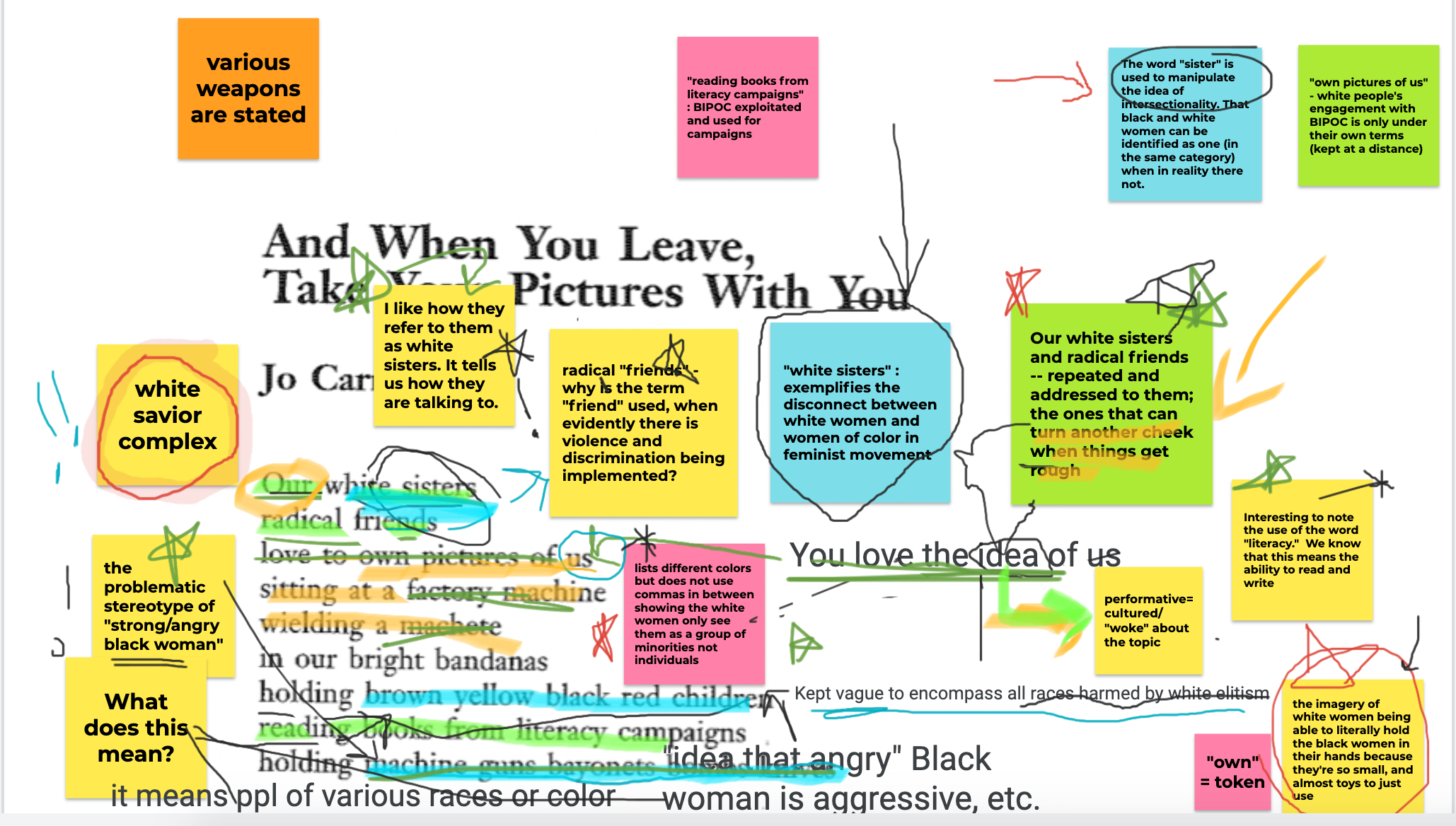

<25>Jamboard provides opportunities for online community-building that move beyond the “post once, respond twice” model. It was my students who first embraced this particular benefit during an in-class annotation exercise on Jo Carrillo’s poem “And When You Leave, Take Your Pictures With You.” At first, students annotated the poem in ways I had expected, underlining key words, circling confusing phrases, and highlighting poignant moments. Yet, their approaches shifted when one student commented in a sticky note that a line from the poem reminded them of “the problematic stereotype of the strong/angry Black woman” (see Fig. 4 below). A few seconds later, another student added a sticky note adjacent to this one, asking “What does this mean?” Though the visual clutter of the Jamboard made it a bit unclear which text this student’s question was actually referring to—was it the adjacent line of the poem or the student’s comment about the “strong/angry Black woman?”—other students quickly responded to both interpretations of the question in adjacent text boxes. Though I had not prompted them to do so, students “hack[ed]” the Jam to make it more conversational in a way that felt much more organic than their interactions on discussion boards. I also expect that the anonymity of the Jam, which allowed students to ask questions without the fear of being “outed” as potentially “ignorant” of social justice issues, likely also facilitated this interaction.

<26>Perhaps my favorite feature of Jamboard is that it gives students a space to affirm each other’s ideas. Again, my students recognized this possibility before I did. In the same Jam session described above (on Carrillo’s poem), I noticed that students started drawing circles, stars, exclamation marks, or arrows around or near each other’s sticky notes (see Fig. 4 above). When I asked students what these markings meant, they shared that they were for comments they “liked” or “found interesting” or “learned something from.” I absolutely loved this development, as it revealed that students were paying careful attention to—and tangibly engaging with—each other’s comments in addition to the primary text. In this case, the Jam provided students a rare opportunity to share their raw excitement for each other’s ideas—something that is difficult to achieve even in the in-person classroom, where one can sometimes only communicate or gauge affective responses through often-imperceptible smiles or nods of the head. Since that day, I have gently invited (but not required) students to underline or star comments they liked—an invitation that they often use and seem to relish, not only as another chance to draw but also as an opportunity to see “what everyone else is thinking,” as one student shared. It is rare to find such a visible example of hooks’s notion of “[e]xcitement . . . generated through collective effort” (8).

Fun

<27>A Jam full of stars, circles, and multicolored sticky notes is not just pedagogically rich; it is also fun—though, as I argue, these are often one in the same. As public health researchers have shown, college students are experiencing an unprecedented mental health crisis, exacerbated (though certainly not created) by the pandemic.(9) What better time, then, to create exercises that are interactive, inclusive, safe, affirmative, and—dare I say—enjoyable?

<28>Scholars in K-12 learning and early childhood education, such as researchers at Harvard’s Project Zero, have argued for a “Pedagogy of Play,” or the creation of learning contexts that allow students to feel “relaxed and engaged” and develop “ownership, curiosity, and enjoyment” in their schoolwork (Tatter). I have found that Jamboard offers a small glimpse into a version of this “pedagogy of play” for college students. At the risk of sounding glib or unacademic, it is, quite simply, fun to play with colors, draw with new tools, make squiggly lines, add smiley faces, and laugh at our bad digital art. While this might seem rather infantile, I propose that this potential for fun is actually no small benefit in this time of global crisis and trauma. In fact, scholars of trauma-informed or trauma-aware pedagogy have advocated for precisely such moments of fun. In an October 2020 presentation for the Arizona Department of Education on “Essential Trauma-Informed Online Teaching Tools,” which is available on contributor Janice Carello’s blog, Carello, Matthea Marquart, and Johanna Creswell Báez suggested incorporating “fun” activities like “webcam dance parties or lip sync before or after class,” “fun videos during breaks,” and “playlist[s] of songs” into online classes. And, most importantly, students long for this. Every time my students and I use Jamboard, at least one student jokingly asks “can we just draw for 30 more seconds?,” or comments on “how pretty the board looks,” or giggles at the visual mess they made. Such chances for light-heartedness, relaxation, and humor strike me as important opportunities to extend what Cate Denial has called a “pedagogy of kindness” that “recogniz[es] that our students possess innate humanity, which directly undermines the transactional education model to which too many of our institutions learn, if not cleave.”

Final Thoughts

<29>Of course, no tool—especially not one so embedded in the throes of global capitalism that has precipitated the worst effects of this pandemic—is going to solve the many and profound problems with remote learning, online access, and higher education in this moment. Yet, my experience working with Jamboard has reminded me that new technological tools can help make things just a little bit better, a little more humane, and a little less stressful. And, when “hacked” by both faculty and students, tools like Jamboard can help remote instructors to do some things just as well—dare I say, in some instances, even better—than in an in-person setting. We just have to play around.

Acknowledgments

I am, as always, grateful for the wonderful students at Siena College, particularly those in The Novel, Women in Literature, and Introduction to Literature, who inspired this pedagogy short and graciously gave me their permission to include the screenshots of their Jams. I also extend deep thanks to Kimberly Cox and Doreen Thierauf for their sharp insights and generous feedback as readers of this piece and co-editors of this special issue.