<1>Upon its appearance in 1834, the only known British anti-slavery gift book, The Bow in the Cloud, was advertised in the contemporary press as a suitable present for Emancipation Day on the 1st of August, when the Slavery Abolition Act came into force (Morning Chronicle, 30 July 1834, Sheffield Independent, 26 July 1834). Looking back from the present, it is easy to take this representation at face value and see the Bow as only a commemorative text to celebrate the successes of abolition, rather than an active political document. Moira Ferguson has claimed that the women-authored poems that make up part of the Bow are spiritually orientated and sentimental, and that the Bow was far less radical than the activism of other abolitionists such as the Leicester-based Quaker abolitionist pamphleteer Elizabeth Heyrick (265, 269, 91 – 112). The compiler of the Bow, Mary Anne Rawson, was a Congregationalist living in the rapidly urbanizing town of Sheffield, and was the Secretary of the Sheffield Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, established in 1825. Between 1826 and 1834, she solicited contributions in poetry and prose for her gift book and received over one hundred and fifty letters in response. Many of her correspondents enclosed contributions with their letters, sometimes writing them on the same pages. Rawson placed these letters and contributions in two manuscript scrapbooks, probably between the late 1850s and the early 1860s, and they now form part of the Bow in the Cloud Manuscripts (BM) collection at the John Rylands Library.(1) This article argues that to approach the gift book as the advertisements in the contemporary press framed it, or to focus on the sentimentality of some women’s poems in the Bow, is to depoliticize Rawson’s gift book project. To do so presumes as well that Rawson deliberately conforms to acceptable gender norms around women’s political engagement. This separates Rawson from contemporaries such as Heyrick, who is celebrated for having championed women’s participation in agitating for immediate and unconditional emancipation. This article demonstrates that Rawson should instead be recognized and understood as a leader of a politicized campaign for abolition.

<2>Women were actively involved in the second phase of the abolition campaign in Britain in the 1820s and 30s. Clare Midgley has shown the central role that women across Britain played in the anti-slavery movement through their participation in establishing provincial anti-slavery societies that distributed print in their local communities. Midgley notes that women’s campaigns were socially conservative, largely restricted to middle-class women, and reinforced accepted gender norms (Women Against Slavery 93 – 120). However, such campaigns also expanded their involvement in the political sphere and provided a framework for the later development of feminist activism (154 – 55, 177). As Elizabeth J. Clapp and Julie Roy Jeffrey demonstrate in Women, Dissent & Anti-Slavery, these campaigns were also deeply shaped by women’s religious identities. For example, Heyrick was both a Quaker and one of the most prolific women authors of abolitionist pamphlets who adopted a radical anti-slavery stance (Midgley, 2011, 90). In her 1824 anonymous pamphlet, Immediate, not Gradual Abolition, Heyrick argues for the immediate emancipation of enslaved people in the British colonies. This marked a departure from the policy of amelioration and gradual abolition that had been advocated by the London Anti-Slavery Society, as well as the opinions of its male leaders (Midgley, Women Against Slavery 103 – 16). Rawson, a Congregationalist, has been seen by historians as more socially conservative than Unitarian and Quaker women abolitionists, and far more hesitant about assuming a public role (Twells, “We Ought to Obey God” 67 – 68). Yet on at least two occasions, Rawson adopted a more radical stance than this image suggests. First, in 1825-26, the Sheffield Ladies adopted the call for immediate emancipation instigated by Heyrick in her 1824 pamphlet. Second, in 1838, as the secretary of the newly formed Ladies’ Society for the Universal Abolition of Slavery, Rawson criticized the male leadership and stepped beyond their authority to send invitations for anti-apprenticeship speakers to visit Sheffield (Twells 70, 76). This information indicates that women’s religious identities, while formative for their activism, do not necessarily indicate their progressivism in any straightforward way.

<3>While the genre of the anti-slavery gift book flourished in the United States, the Bow is the only one known to be compiled and published in England.(2) It is a rare example of an entire gift book advocating a political cause in a sustained way (Harris, Forget Me Not 167). Abolitionist poetry often appeared in gift books, and some abolitionists were editors of gift books, notably Thomas Pringle.(3) Poetry collections of abolitionist verse were common, but they did not have the material features that were central to the gift book form, such as beautiful front covers and an engraved title page. The Bow offers an opportunity to examine not only the political significance of the gift book as a genre, but also Rawson’s important role as a compiler of an anti-slavery gift book. While scholarship has been attentive to Rawson as a historical figure and her role in the abolitionist movement, her role in literary culture has not been fully elucidated.(4) This article offers a holistic approach to Rawson’s career, one that considers both her writing and the gift book alongside the extensive correspondence relating to its compilation, which presents an opportunity to better understand her political radicalism. Examining the interplay between the print book and the manuscript scrapbooks that Rawson compiled and kept recovers an important aspect of women’s anti-slavery campaigning and writing by looking at the cultural practice itself. This approach reads Rawson’s collection in the cultural terms in which it was created, and demonstrates the radicalness of Rawson’s project and campaign strategy.

<4>The first section of this article examines Rawson’s production of the Bow, reading her scrapbooks as material reflections of her network. The compilation of the Bow relied on Rawson’s social network within her larger campaigning circle, both of which overlapped with the professional and social networks of annual contributors and editors. The production of the gift book relied on male and female contributors and correspondents, and through the socially acceptable mode of letter writing, Rawson collaborated with men and women in a way that was unusual in the abolition movement. This section includes a data visualization of Rawson’s networks to illustrate how these connections informed the production of the Bow. The second section compares the wide public circulation of the Bow with the private sharing of Rawson’s manuscript scrapbooks among a smaller circle, in the wider context of manuscript circulation between members of women’s abolition societies. Focusing on the scrapbooks, it explores these as a feminist project in which Rawson created her own voice and history as a campaigner by carefully placing together the letters and contributions she received. It considers how some of the poems retained in the manuscript were more radical than those included in the printed Bow, to argue that Rawson targeted their circulation to a smaller circle of committed women abolitionists.

Production of The Bow in the Cloud

<5>Literary networks, often sustained through written correspondence, were central to women’s writing in the Romantic era, especially outside formalized print networks (Winckles and Rehbein 1 – 15). The Bow illustrates that Rawson created a correspondence network and used this to collect contributions for her gift book. She also used her network to gain advice on some of her editorial decisions. The Bow reminds us that writers such as Rawson were part of wider literary culture in the Romantic era and that in recovering women’s abolitionist writing we need to be attentive to manuscript culture and circulation. Scholars have begun to disrupt the narrative that the rise in print culture saw a decline in manuscript culture and circulation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Levy 3). Michelle Levy explains that authors operated in a “multimodal world” where individual literary texts could enjoy “a double life, moving between script and print” (265). For women authors, print was not always the ultimate goal (Winckles and Rehbein 7). Within studies of abolitionism, work by scholars such as Ryan Hanley has shifted debates towards an exploration of how networks were central contexts for the production and circulation of print culture. As John Ernest notes, scholars have only recently begun to examine the compilation, production and circulation of abolitionist print culture (13) and manuscript culture may fill the gaps in our understanding.

<6>In creating the Bow, Rawson mimicked the genre of the literary annual. Literary annuals were collections of verse and prose pieces often compiled by famous authors. They were a popular genre on both sides of the Atlantic in the 1820s and 30s and were often given as gifts. Gift books were very closely related to the annual genre and shared many of their features, but a key difference was that they were only intended to be published once, rather than for a succession of years (Harris, “Borrowing, Altering and Perfecting” 20).(5) Predominately aimed at a female readership and with a “gendered, sentimental reputation”, gift books were beautiful objects, with gilt-edges, silk or morocco leather bindings, and engraved title pages (Fritz and Fee 62). Unlike anthologies that could collate published and unpublished works, the annual genre collected together original and previously unpublished materials (Harris, “Borrowing, Altering and Perfecting” 16). Rawson’s letters mention several annuals – the Amulet, the Landscape Annual, and the Literary Souvenir (Anti-Slavery Letters and Papers letters 33, 42) – demonstrating familiarity with their form and content, which allowed her to adopt their successful features. In Rawson’s hands, however, the gift book genre functioned like a petition, listing as its contributors the names of those who wished to make a public statement of their deep and individual feelings against the continuation of slavery in the British colonies. For contemporaries the names of the contributors mattered more than the creative content. In a letter dated 31 July 1834 to thank Rawson for a copy of the Bow, contributor Eliza Conder playfully describes quickly “reading” the gift book and focusing on two aspects in particular: checking whether the printer had made any errors and identifying the names of the other contributors to find out “who are our companions?” (BM Letter 16).

<7>The annual and gift book genres were associated with memorialization and a desire to capture the present moment. For example, Sara Lodge examines how letters are part of the rhetoric of memorialization in Romantic-era gift books and were seen as preserving the letter-writer’s presence and body (29, 31). Katherine D. Harris notes that contemporaries saw the annuals as “represent[ing] memories,” and editors “offered the literary annuals as a living moment” (Forget Me Not 10, 5). Speaking to these contexts, the Bow allowed Rawson to create a printed memory and memento of the moment, one that recorded the sins of colonial slavery and that served as a permanent reminder of the struggle of abolitionists. Gift books were treasured objects associated with sentimentality, and there was an expectation that they would be prized by their owners. In a letter in 1826, Rawson wrote that the Bow would be “calculated to enlighten the judgement and affect the feelings”, and stated that the gift book would “arrest the attention” and help to win people over to the abolitionist cause in a print marketplace saturated with pamphlets (Anti-Slavery Letters and Papers letter 33).

<8>The material form of the Bow would have placed it within the recognizable annual genre. The Bow has an engraved frontispiece from a design by H. Corbould, who was a well-known steel plate engraver. Well aware of commercial trends and popular tastes, he was involved in several successful serial projects including the artwork for Forget Me Not (Harris Index). For the Bow, Rawson also chose the same kinds of binding as the successful literary annuals: foolscap octavo in expensive green and red morocco leather.(6) The Bow brought together the work of notable literary figures, abolitionists, members of parliament, and Congregationalist ministers. Rawson included the work of eminent authors with experience of editing and writing contributions for annuals. In this, Rawson was like other annual editors who, as Barbara Onslow has noted, drew on “interlocking circles” of friends, acquaintances and family for contributions (76). For example, her contributors included Thomas Pringle, the secretary of the London-based Anti-Slavery Society in 1827-34 and editor of the annual Friendship’s Offering, and James Montgomery, the poet, hymn-writer and abolitionist. Montgomery and Pringle corresponded, and Montgomery had contributed to the Friendship's Offering (Miscellaneous Letters to James Montgomery letter 702).(7) Both advised Rawson on her curation of the Bow.

Visualizing Rawson’s Network

<9>Looking at the statistical and demographic breakdown of Rawson’s correspondents enables us to examine how her social network informed the production of the Bow. Rawson’s correspondents included Congregational ministers, men and women abolitionist leaders such as Lucy Townsend, the secretary of the West Bromwich Ladies Society, the first women’s abolitionist society established in Britain, and Thomas Clarkson, Ralph Wardlaw and James Douglas, all Glasgow Congregationalist ministers who spoke against slavery.(8) During the process of writing to potential contributors, Rawson exchanged letters with Members of Parliament, esteemed writers, and women friends. These letters were ostensibly about contributing to the gift book, but also performed a range of other functions, such as providing windows onto the abolitionist debate in Parliament, forging and sustaining social relationships with campaigners and literary figures, and sourcing recommendations for anti-slavery reading. Rawson’s top correspondents in terms of the number of letters she received were Montgomery, Pringle, and the Rev J.W.H. Pritchard, the Congregational minister of the Attercliffe Zion Chapel where Rawson and her family worshipped. Her top women correspondents were Eliza Conder, Elizabeth Abney Walker, and Ann Gilbert. Conder lived in Walford northwest of London. Her husband Josiah had strong Congregational links and was the editor of the Eclectic Review between 1814 and 1837. In 1839 he became a member of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. Abney Walker was an abolitionist living at Clifton House in Rotherham. Gilbert, the wife of a Congregational minister, lived in Nottingham and wrote successfully for children with her sister.

<10>While previous analyses have tended to focus entirely on women’s poetry in the Bow, such a focus overlooks the greater number of men correspondents and contributors. Of one hundred and fifty-four letters in the Bow Manuscripts, twenty-one percent were from women correspondents and seventy-nine percent were from men correspondents. Rawson’s ability to work on a project that involved men and women was unusual within British abolitionism, in which women had separate anti-slavery societies and engaged in gender-specific activities. Having men correspondents within women’s literary networks could represent an earlier phase in some individual women’s access to the world of print (Beshero-Bondar and Donovan-Condron 142). However, in Rawson’s case, given the gendered nature of campaigning and the strict limits around what was deemed appropriate in terms of women’s political engagement and public activities, the letters represent a more open space where she could collaborate with men and women writers. This encourages us to look beyond the apparent sentimental and ameliorationist message of the women-authored poetry to give more holistic consideration to men and women’s contributions in Rawson’s creation of her gift book.

<11>The publication date of the Bow in 1834 seems to support a reading of it as a reflective document that aimed to celebrate for posterity the 1833 Abolition Act coming into effect. However, Rawson’s letters remind us that she was curating this collection in a much more heated political context, before the Act was passed and during the first half of 1833 when many abolitionists expressed their dissatisfaction with plans for compensation for slave owners and with the apprenticeship system. The volume of Rawson’s correspondence peaked in three specific years before the gift book’s publication in 1834: 1826, 1833 and 1834. Of one hundred and thirty-two letters that contain legible dates, Rawson received thirty-two in 1826, eighty-one in 1833, and seventeen in 1834. This reflects the gestation of the project and its political context. Rawson began the gift book in 1826, during a period of intense abolitionist campaigning on a national scale. In 1823, the new Anti-Slavery Society was formed, and the Sheffield Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, one of the many women-led anti-slavery societies across Britain, was established in 1825, with Rawson as a founding member and the society’s secretary. Rawson was working on the collection throughout 1833 and into 1834. This was a period of fervent abolitionist activity and interest, with debates raging in Parliament. During the first half of 1833, many abolitionists opposed proposals for the compensation scheme for slave owners and the apprenticeship scheme. Far from ending the abolitionist campaign, there were moves in April 1834 for a shift towards the universal abolition of slavery, with an initial focus on the United States.

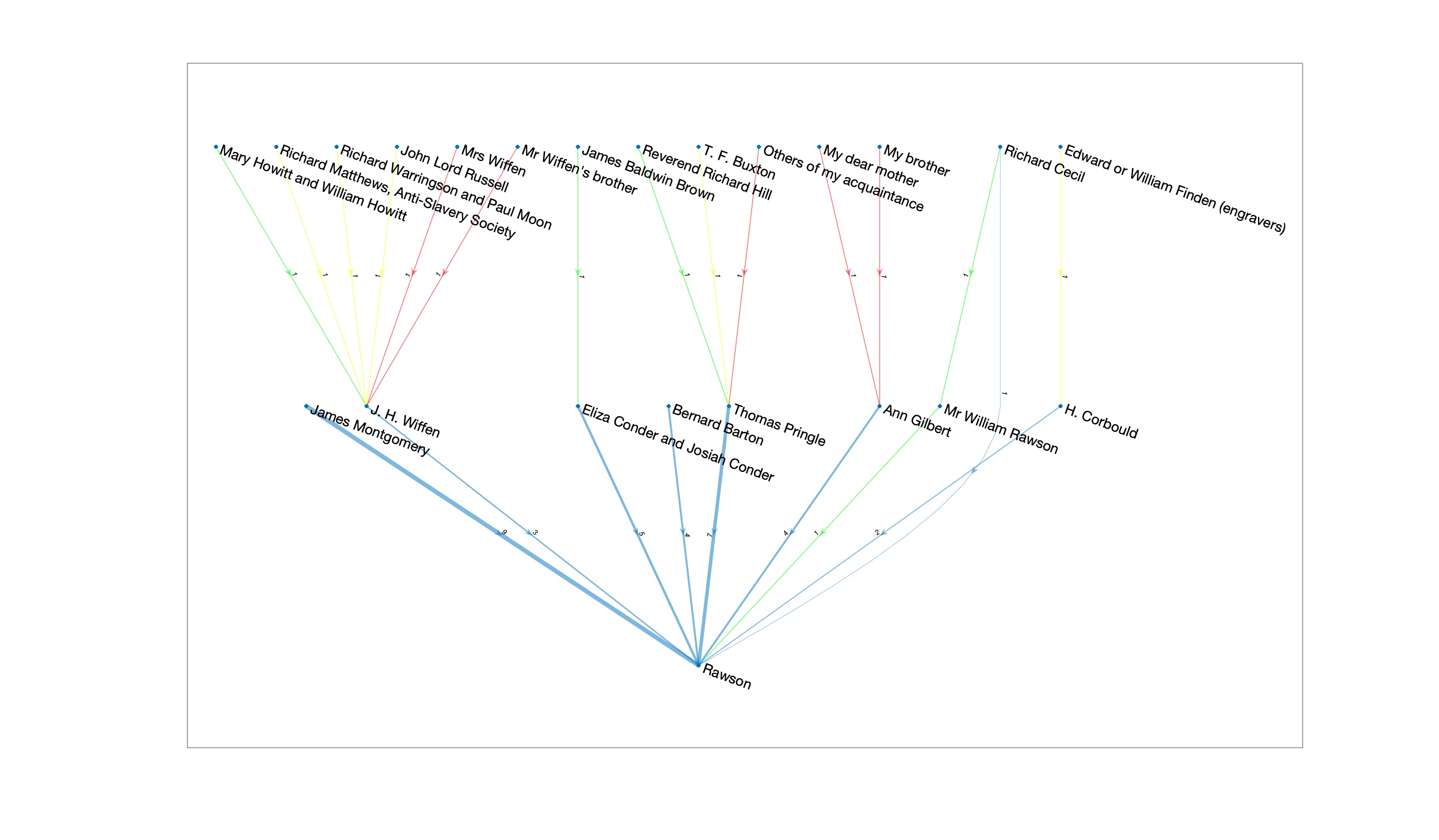

<12>From her base at Wincobank Hall in Sheffield, Rawson maintained a network that, based on the one hundred and forty-nine letters it has been possible to locate, stretched across England and Scotland. The highest numbers of letters came from Sheffield and Rotherham (twenty-eight), London (thirty-nine) and Nottingham (eleven). This suggests that the networks Rawson retained from the places she had lived – Sheffield and Nottingham – helped to shape the gift book.

|

List of contributors, following the order of the contents page in the gift book Bernard Barton James Montgomery Ann Gilbert Joseph Watson Eliza Conder Allan Cunningham Archdeacon Wrangham William Howitt Mary Howitt Rev R. W. Hamilton Jeremiah. Holmes Wiffen Miss Ball James Baldwin Brown Mary Sterndale John Bowring James Edmeston P Moon James Agnes Bulmer Joseph John Gurney T. R. Taylor Rev William Knibb Miss Maria Benson Rev J. W. H. Pritchard Rev. Edward William Barnard Elizabeth Jones George Pilkington Rev W. Knibb Dinah Townley William Howitt Rev Joseph Gilbert James Riddall Wood Josiah Conder Jane Hornblower nee Roscoe John Holland Thomas Pringle Richard Hill Rev Eustace Carey R-C-L. Samuel Carter Hall J. R Rev J Pye Smith Matthew Bridges Thomas Burchell Elizabeth Abney Walker James Douglas Lucy Townsend Rev Chauncey Hare Townsend Anthony H. Smith Edward Henry Abney Lord Morpeth Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton John Parker Rev John Ely Rev Thomas Hill J W H Pritchard Rev James Townley From the Emerald Isle Sarah J Williams Rev William Marsh Maria Stevens Rev. Thomas Best Charlotte Elliott John Sheppard |

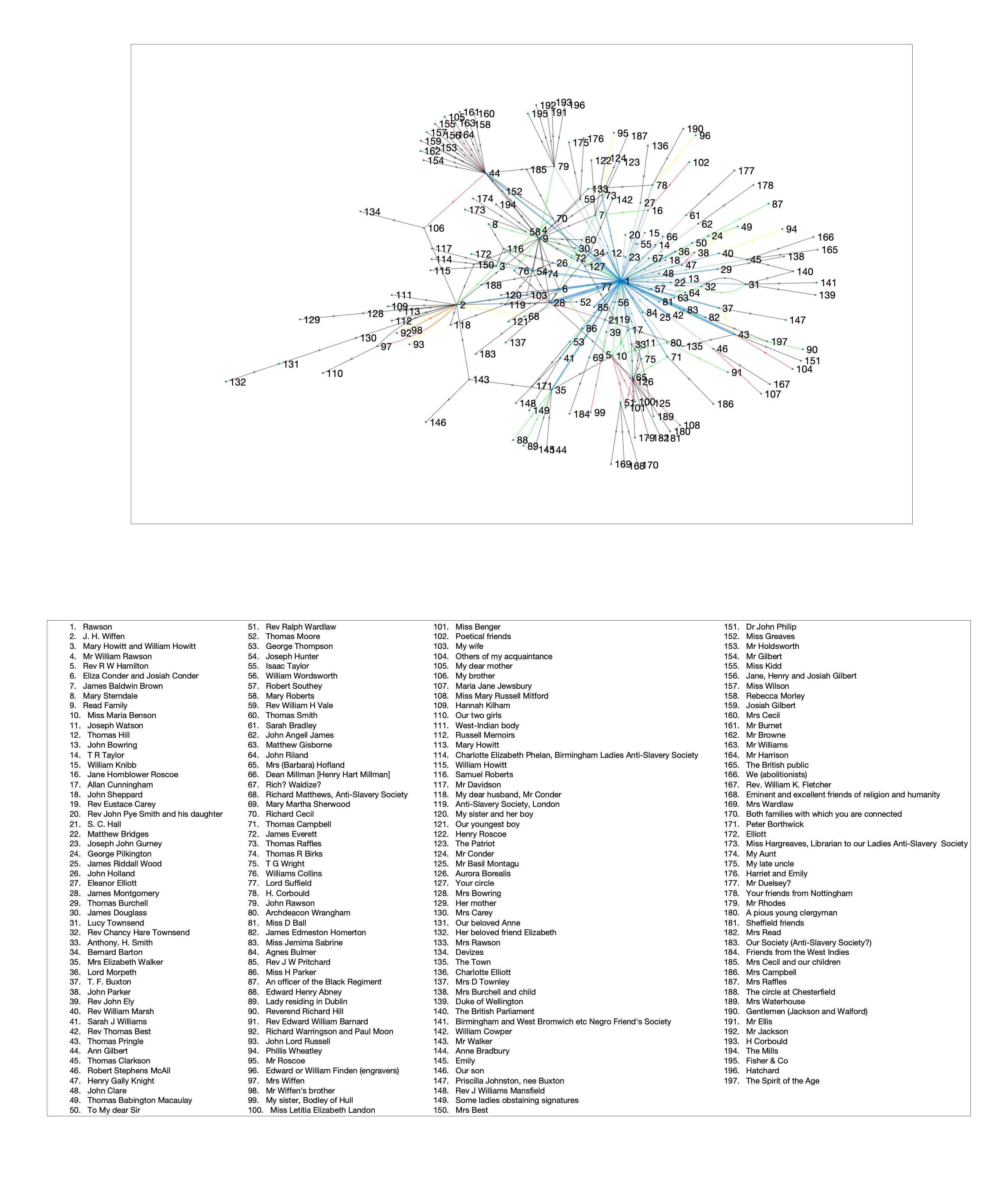

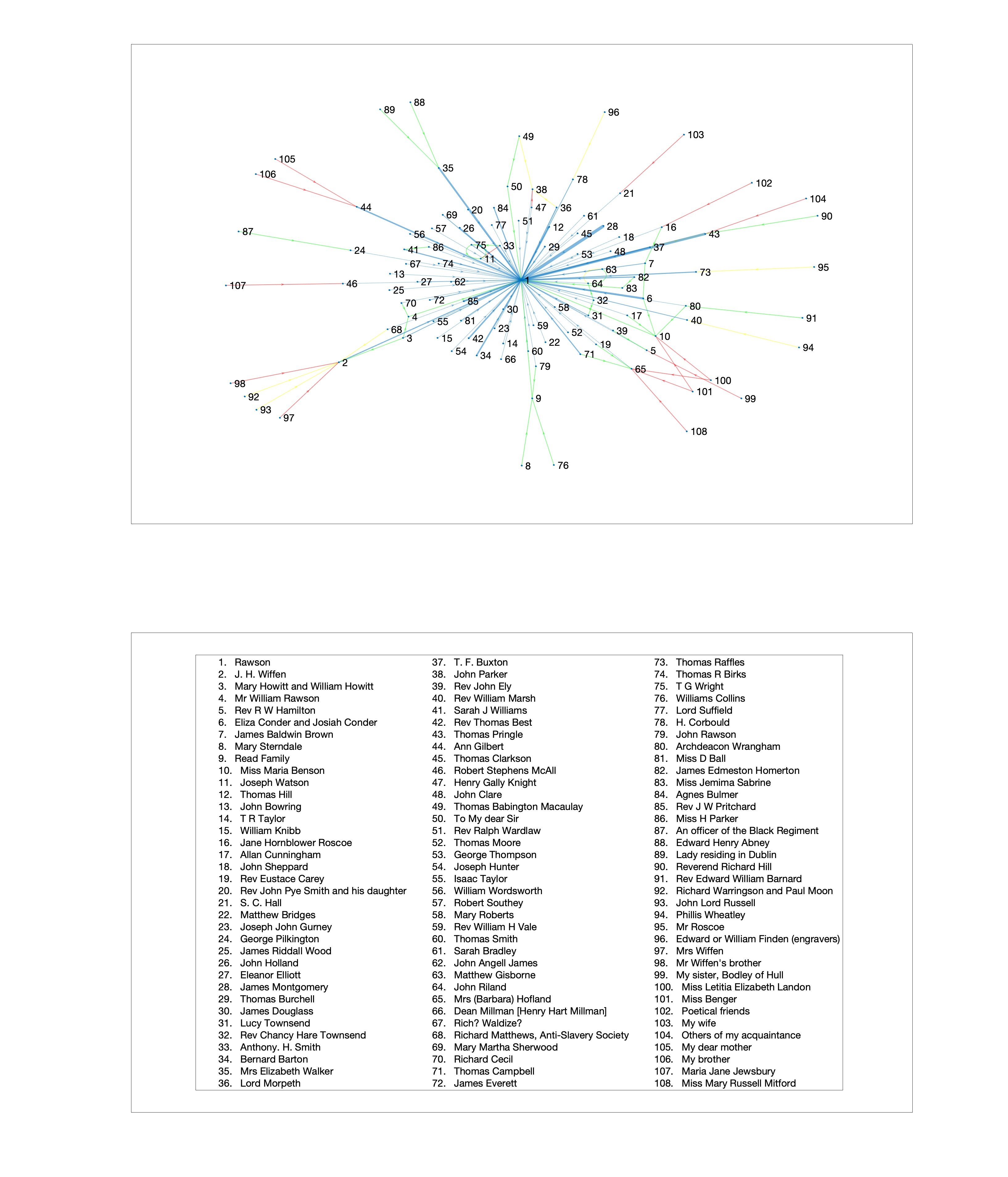

<13>Visualizing the data as network graphs demonstrates the complexity of relationships between the contributors to the Bow. It shows there is a dense web between correspondents and their social worlds, as crafted in the letters, and that the gift book depended on other relationships, and not only on the direct relationship between Rawson and her correspondents. Figure 1 visualizes the people and relationships involved in creating the Bow based on the information about individual people contained in Rawson’s letter collection. Each node represents an individual person (or, less often, a group, organization or print publication) and they are linked to other individuals by edges that represent a connection between them. This graph uses information about people and organizations contained within the text of the letters. Figure 2 shows the people and relationships but removes the references to people, places and organizations contained in the body of the letters, and includes a key of names. The expansiveness of the Figure 1 and 2 graphs shows that the wide-ranging network was essential to completing the book. Rawson wrote to well-known figures such as William Wordsworth, Robert Southey and John Clare. Some of Rawson’s correspondents were supportive and some were not, but the fact that they replied indicates her social standing and the strength of her social network. In Figure 1, the black edges visualize the wider social world contained within the letters by showing how individuals and organizations such as Montgomery and the London Anti-Slavery Society became a common frame of reference for Rawson and several of her correspondents.

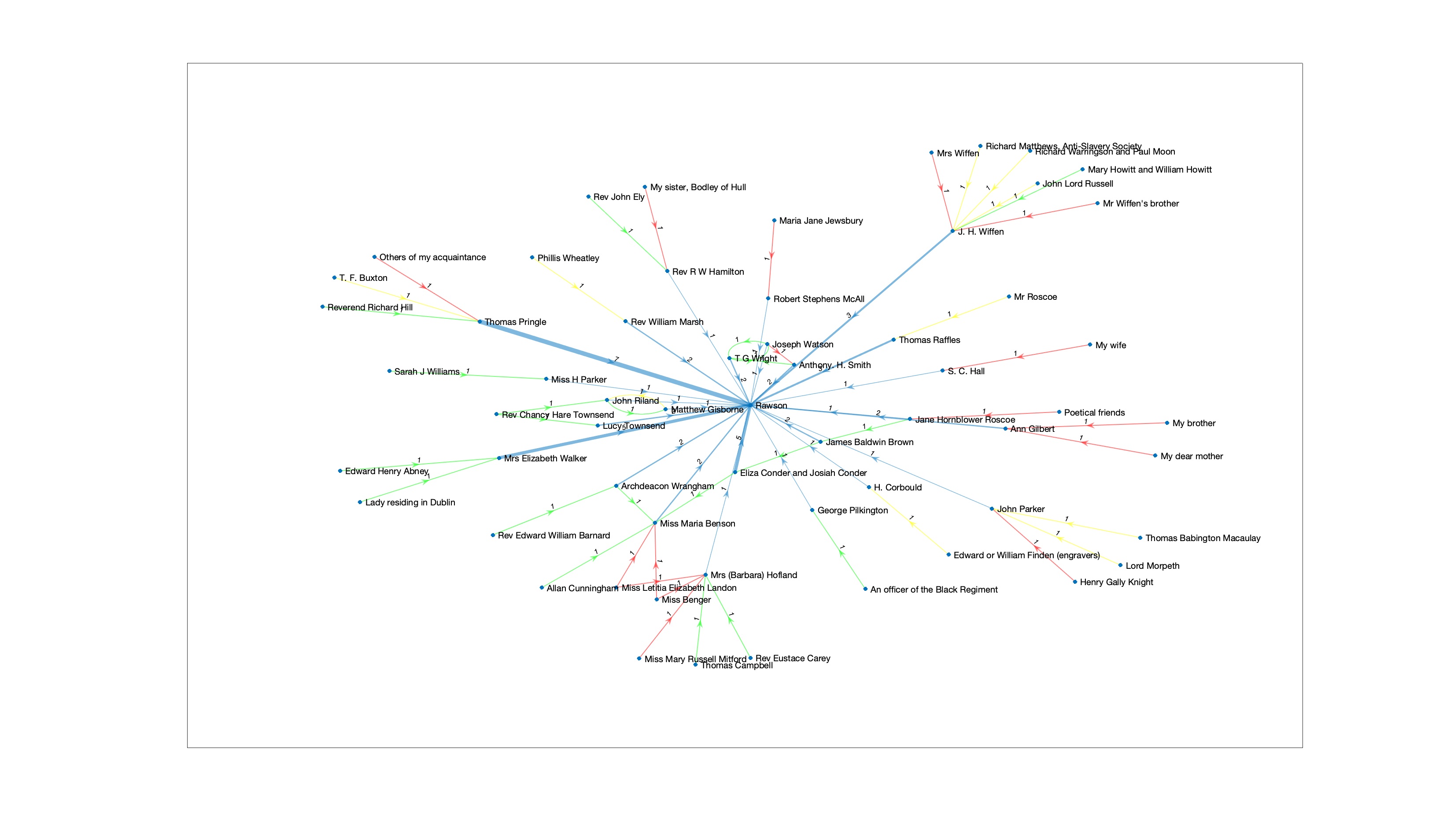

<14>Men and women correspondents frequently made suggestions for contributors, and sometimes forwarded poems on their acquaintance’s behalf, as visualized in Figure 3. Mrs Walker forwarded part of her own letter with a contribution from Edward Henry Abney to Rawson. Rawson’s network of contributors often knew her family and passed on regards to them, and correspondents often mention other individuals from whom Rawson was receiving letters: for instance, Eliza Conder mentions Montgomery, and the Gilberts mention Richard Cecil. The green, red and yellow edges represent when a correspondent facilitates a link between Rawson and a new individual. The green edges show when a correspondent successfully informs and encourages someone to contribute or passes on a contribution to Rawson on somebody else’s behalf. This illustrates how certain individuals could be super-spreaders, distributing knowledge about Rawson’s collection, and inspiring others to contribute. This graph shows how letter-writing enabled Rawson to stretch her reach into her correspondents’ social circles and demonstrates how interwoven and connected the lives of her correspondents were. It also suggests that the process of compiling such a volume created an opportunity for relationships and connections between individuals to flourish.

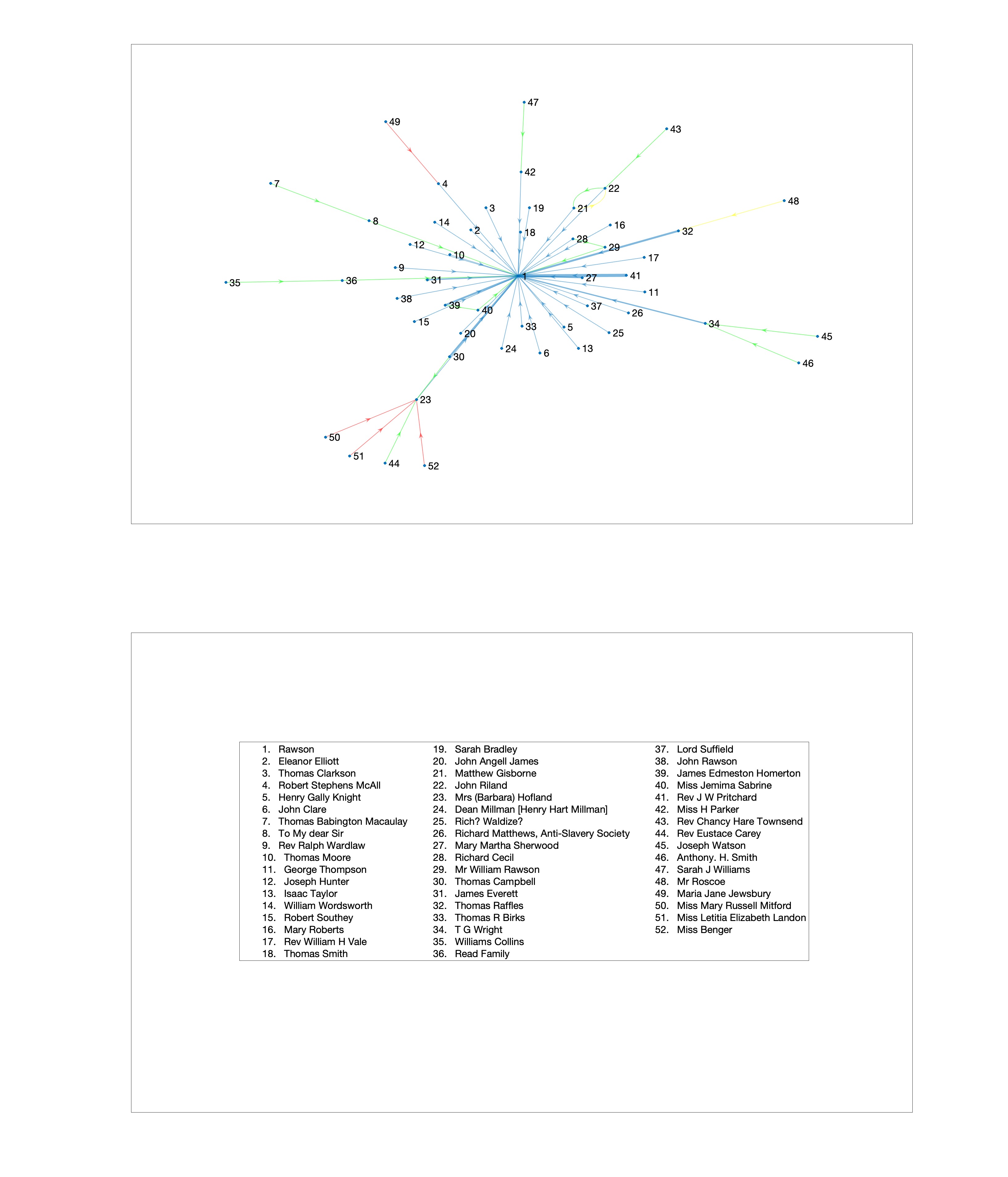

<15>Some of Rawson’s correspondents went beyond providing a contribution and gave her editorial advice and support in compiling the gift book (Figure 5). Their recommendations for the title, preface, engraved frontispiece and motto show that there was a communal element to her editorial approach. These paratextual spaces of her printed book, which framed the way the contents were asked to be read, finalized last by Rawson and seen as needing to be more sensitive to the immediate political context, were more collaborative than other parts. Rawson received advice by letter on the title of her volume from the Quaker poet Bernard Barton, Eliza and Josiah Conder, Ann Gilbert, the Quaker librarian at Woburn Abbey Jeremiah Holmes Wiffen, the Sheffield-based travel writer Mary Sterndale, Montgomery and Pringle. All eight had prior experience of writing for publication, as newspaper and annual editors and contributors. The Congregationalist minister Richard Cecil wrote a draft advertisement for the Bow, which Rawson drew from heavily in writing her Preface.

<16>Montgomery’s letters to Rawson reflect a particular kind of relationship between them. The frequent and hurried notes that he sent her, often without full dates, and in quick succession, suggest informality and reflect their proximity to each other, as both lived in Sheffield. Although we only have one side of the correspondence, the letters suggest that Rawson encouraged Montgomery’s involvement and advice when it came to putting together certain parts of her volume, particularly the Preface, motto and titles for some poems. Nine letters from Montgomery in the Bow Manuscripts show that there is a thick interchange of letters between March 1833 and May 1834. The letters show they had a close collaborative relationship as Rawson formatted, finished and polished the contents of her collection. Montgomery suggested titles for individual contributions and seems to have provided Rawson with close-at-hand support as she went through the final stages of bringing her book to press (BM 18 Jan 1834 Letter 81). On 8 May 1834 Montgomery wrote to Rawson ‘[i]n very great haste’ and gave his comments on the title page and Preface which he had proofread (BM Letter 83). Montgomery also sent more informal and brief letters to Rawson than she received from her other correspondents, suggesting a more intimate and close friendship. For example, a brief letter with no postmark, which was probably delivered by hand, was signed off “10 o clock Thursday evening” and accompanied the “proofs.” Montgomery frequently informed Rawson that he was writing in haste and unable to answer her at length, suggesting a sense of urgency in sending his replies and copies of proofs to her.

<17>Rawson involved Thomas Pringle in decisions about the title of her gift book. Her appeal for his advice may have been a tactical decision to encourage his involvement in the creation of the volume and to invest him with some concern about its success. Pringle’s seven letters to Rawson between February and December 1833 show there was a dense web of contact between them. His support was significant given his status as the secretary of the London-based organizational centre of the national abolition movement. In 1826 Richard Matthews, then the secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society, wrote to Rawson informing her that he hoped to produce a contribution for her. In a letter dated 16 March 1826, Jeremiah Holmes Wiffen had suggested this contact (BM, Letter 31). Her letters to and from Pringle mapped onto the contact she had established with his predecessor. Pringle offered to circulate the prospectus for Rawson’s book using the network already established to deliver print to the provincial anti-slavery societies: “I could send out a couple of hundred copies through the country” with the monthly deliveries. He also offered to mention the work “to others of my acquaintance” (BM 27 Feb 1833 Letter 140).

Rawson’s Preface and Letters

<18>Rawson produced her gift book, in part, to commemorate the Abolition Bill of 1834, but she also wanted to preserve the memory of the guilt and national shame of British colonial slavery. Rawson’s Preface and the letters sent to her show that, rather than producing a reflective and backward-looking document, she was already aligning herself with the short-lived movement in 1834 for the Universal Abolition of Slavery, which later reignited with the renewal of the national campaign in 1837. Rawson’s Preface in the Bow itself was a kind of pamphlet and her gift book a collection of voices designed to remind the British public and abolitionists of the sins and horrors of slavery, and push forward in the fight for its extinction globally. Looking more holistically at Rawson’s writing offers an opportunity to re-evaluate her project, and to reflect upon its rebellious and radical aims.

<19>Still the purpose of Rawson’s gift book is hard to decipher completely. In her Preface to the Bow and the letters she sent, Rawson apologizes for the confused nature of her volume, suggesting that it may appear out of date in light of the recent passage of the Abolition Bill (MS 724, Letters 36 and 40). Rawson waited until the last moment to provide a title and a preface for her volume, acknowledging that the abolition campaign was still unfolding in early 1834, despite the passage of the bill in August 1833 to come into effect the following year (MS 742 Letters 10 and 35). When it came to writing her Preface, Rawson was heavily influenced by the wording of the address To the Anti-Slavery Associations, and the Friends of Negro Emancipation throughout the United Kingdom by the short-lived Agency Society for the Universal Abolition of Negro Slavery and the Slave Trade throughout the World on 14 March 1834. This address drew British abolitionists’ attention to the global existence of slavery, with some five million fellow human beings still enslaved. It highlighted slavery in the United States and the use of British capital in the slave trades in the French, Spanish and Portuguese colonies. Rawson’s copy of this address, in the Wilson Anti-Slavery Collection, shows handwritten marks next to part of the address, which she drew from and referred to in her own Preface. A draft version of Rawson’s Preface, written on the back of an envelope that appears to have originally contained the contribution of Rev Eustace Carey, shows that she targeted slavery in the United States as one of the evils she wanted to see defeated. The prospectus for the Bow also invites readers to see it as an active political tool. It describes the gift book as showing the “[e]vils of slavery”, as well as commemorating “its abolition in the British colonies” (BM).

<20>In creating the gift book, Rawson cut and pasted from the letters she received to produce its textual fabric. In Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton’s letter, he used large crosses to mark out the part of his letter that he gave Rawson permission to use as his contribution, which she printed (BM Letter 117). John Sheppard wrote to Rawson on 22 March 1834, including a poem on the same sheet, and informed Rawson that he had written a poem, the “so imperfect a trifle which I send”, “this morning” (BM Letter 12). This indicates the temporal closeness between the compilation of the poem and the letter. There is only one letter from Samuel Carter Hall. It shows that he quickly responded to and dealt with Rawson’s request in sending a poem. In his letter dated 15 May 1833, Hall half-apologetically noted that he only received Rawson’s note the day before, perhaps to allow for sending her an unoriginal work. He wrote his poem, “The Cup of Gold”, on the back of his letter on the same sheet and informed Rawson that he had already published this anonymously in his newspaper, The Town (BM Letter 97). Rawson’s decision to print Hall’s poem subverted the expectation that the gift-book genre should only contain original contributions. It is not possible to know why Rawson made an exception in Hall’s case. Perhaps, she hoped few people had seen it previously as Hall had originally published it anonymously in a weekly newspaper. She may have otherwise been motivated to include it because of Hall’s prestige as the editor of the Amulet.

<21>The number of letters Rawson received through 1833 shows that the Abolition Bill did not dampen her desire to publish her gift book. In a letter from the abolitionist leader Thomas Clarkson, from Ipswich, Norfolk, dated 14 April 1833, Clarkson reveals something of Rawson’s letter to him: “I am obliged to you for your wish that I may live to record the total abolition of slavery” (BM Letter 155). The use of language reflects Rawson’s stance for total and complete abolition, without the period of apprenticeship, and it anticipates her move in writing the Preface in the Bow the following year to evoke the language of the Agency Society for the Universal Abolition of Negro Slavery. This desire is one shared by many of her contributors, whose attitudes sometimes became more progressive over time. For instance, in May 1833 Eliza Conder noted that the public feeling was becoming “increasingly intense” (BM Letter 14), and Ann Gilbert wrote to Rawson from Nottingham in May 1833 about the vigorous campaigning efforts of women in Nottingham, who collected fifteen thousand women’s signatures for their petition in support of emancipation (BM Letter 151). On 12 May 1833, J. H. Wiffen expressed his disillusionment and his hope that the public papers were incorrect in stating that the government wanted to propose a period of apprenticeship, which would mean “twelve years more of principle effect – sacrifice and labour – to obtain the consummation so seriously to be wished” (BM Letter 32), of complete emancipation. Lucy Townsend wrote to Rawson on 14 May 1833, the day before Parliament was to make a decision on slavery, and mentioned this to Rawson in her letter. On 17 June 1833, Rev Chauncy Hare Townsend in Keswick wrote to Rawson telling her that she could alter line ten of his sonnet, “And wavering counsels planned by selfish men!”, if she judged this to be best, as it reflected his critical view of those advocating “half and half measures” (BM Letter 107). In his letter dated 28 June 1833 Joseph Watson stated that he did not agree with the period of apprenticeship or compensation for slave owners “which the ministerial plan sanctions” and welcomed Rawson’s work, which he saw as able to rouse the public and push for a “more humane, just and speedy measure of emancipation” (BM Letter 13). In her letter dated 3 November 1833, the writer and Unitarian Jane Hornblower Roscoe, whose father had been an abolitionist in Liverpool, wrote: “I cannot but lament that it was not a fuller and more immediate emancipation on many accounts” (BM Letter 6). Roscoe provided a poem, passed to Rawson by James Baldwin Brown in 1827, entitled “Sonnet: The African Mother,” and later went on to contribute to the American anti-slavery gift book The Liberty Bell. Other correspondents noted their satisfaction with the passage of the Abolition Bill, while many, notably William Wordsworth, declined to contribute and spoke of their anxiety of inciting slave rebellions.

<22>In addition to the voices of white abolitionists, the Bow contained texts by Black authors who had connections to Black Atlantic rebellion. In 1833, Rawson approached Thomas Burchell to write about the economic advantages of free labor. Burchell was a Baptist minister and abolitionist in Montego Bay, Jamaica. He was suspected of involvement in the Baptist War Slave Rebellion in 1831 and had links to the abolitionist Samuel Sharpe. He published his contribution anonymously because he feared the outcry of West Indian planters and was due to return to Jamaica at the time of writing. The intellectual equality of Black and white people was a strong impetus for some of the contributors’ writing. William Marsh’s contribution to the Bow includes extracts from the poetry of the African American poet Phillis Wheatley. George Pilkington provides a narrative related by his friend, an officer of the Black Regiment, “The Black Soldier”. Similarly, Rawson included the contribution of the Black abolitionist Richard Hill who had previously written for other annuals and gift books. Hill wrote a description of his travels to Haiti for Rawson’s volume, “The Creole Maiden’s Song,” and Pringle facilitated the link between Hill and Rawson, suggesting his inclusion and forwarding Hill’s contribution on to Rawson in his letters to her. (9) In 1830, the Anti-Slavery Society commissioned Hill to undertake research on Haiti. Rawson’s desire to represent the work of Black abolitionists in the Bow is evidence of her intention to work within a literary network that advocated not only on behalf of, but alongside, Black people.

Circulation of the Bow and its Scrapbooks

<23>The printed Bow had a wide public circulation. Rawson’s publishers, Jackson and Walford, in a letter dated 10 May 1834, mentioned that five hundred copies of the gift book would be printed and sold for 12 shillings each (Anti-Slavery Letters and Papers). This section focuses on two scrapbooks that Rawson made that contained materials relating to her compilation of the Bow: the letters and poetry and prose contributions she received, drafts of the contributions in her own handwriting, and autographs, newspaper cutting and photographs. The scrapbooks are a collection in their own right and can be understood not only as Rawson’s attempt to store her papers relating to the gift book, but to preserve a record of her relationships and a memory of her writing project. In her scrapbooks, Rawson accumulated contemporary ideas while she also authored an archive of her own voice. While maintaining an appearance of gendered conformity in her abolitionist work, Rawson collected and layered together the letters and contributions of people in her social network and in doing so she preserved and created a story of her own campaigning activities and connection to literary and political culture. Rawson’s Bow in the Cloud scrapbooks contain poems about slave insurrection that demonstrate that she kept and circulated more radical poetry in manuscript form rather than print.

<24>It is likely that a more intimate circle of Rawson’s family and friends circulated the Bow scrapbooks instead of the printed gift book. Ellen Gruber Garvey examines how, in the nineteenth century, ordinary Americans created scrapbooks: they clipped scraps from newspapers and magazines and pasted them into new contexts. Garvey shows that scrapbook makers were “part of an elaborate circuit of recirculation”: when they gleaned texts and lifted them into new contexts they created “a new tier of private circulation” with new meanings (“Scissoring and Scrapbooks” 208). She shows, in Writing with Scissors, that scrapbooks partly came out of the commonplace book genre – popular since the Renaissance – in which readers copied out portions of texts and which could be records of reading (15). Scrapbooks had close links to the diary genre (15). They were “filing systems” which people compiled to tell their own stories (4, 22). This made them “a form of life writing … that preserves elements of life experience and memory cues” (15).(10) While there is no evidence in the Bow scrapbooks of how they were circulated and among whom, women’s anti-slavery societies in Britain certainly co-created and shared manuscripts. In 1828, the Female Society for Birmingham produced anti-slavery albums that were communal and designed to be passed around amongst their women members (James and Shuttleworth 47 – 72). The Sheffield Ladies also produced an album, the Negro’s Album of the Sheffield Anti-Slavery Society in 1828, and this was filled with handwritten poems and had a handwritten title page. The Sheffield Ladies had their own librarian who apparently kept track of these manuscript books. Mary Roberts told Rawson that the librarian had informed her that the album was at “White House” but that she would be able to procure it and send it on to her (Letter 167). Michelle Levy’s Literary Manuscript Culture in Romantic Britain establishes that manuscript culture and circulation within close circles was prevalent during this period. The ornate brass metal clasps and the lettering on the embossed spines of the scrapbooks, stamped “Autographs: The Bow in the Cloud, Vol 1 and Vol 2.” suggest that they were designed to be displayed, perhaps on a bookshelf. The poems and letters appear not to have been stuck down and this meant that readers could have lifted out a single poem or letter for study and discussion. There was a long tradition in Britain of women dating back to the English Civil War circulating radical poetry in manuscript form amongst their family and friends, and Rawson’s scrapbooks seem to fit within this tradition.

<25>The scrapbook genre allowed Rawson to accumulate contemporary ideas about slavery while creating an archive of her own experience. Creating the scrapbooks also allowed Rawson to save her manuscripts from being lost, forgotten or separated. Garvey examines how, after the US Civil War, Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, whose son had died in the war, created scrapbooks of poems from newspapers that related the experiences of soldiers during the war. She shows how Bowditch used the voices of the soldiers to connect his personal grief over the loss of his son to a moment of national mourning “to experience his grief as something in common with his fellow citizens” (“Anonymity, Authorship, and Recirculation” 175). Similarly, Rawson placed the letters and contributions she received into the scrapbooks without cropping or editing them, and thus created a record of her contemporaries’ attitudes. By presenting these voices wholesale, Rawson connected to a moment of national reflection on the legacy of British colonial slavery in 1833-34 and placed her own abolitionist ideas and activism within this wider context. The scrapbooks therefore not only preserve the contributions and letters but collate a vaster archive that represented a wider social network than was involved in the printed version. Moreover, as many of those who declined to contribute gave a range of views on the “slavery question” such as hesitancy around immediate emancipation, Rawson’s manuscripts reflect a more multivocal response to slavery than the printed Bow. The scrapbooks contain ten thank-you letters, twenty-two letters from those who declined to contribute and one hundred and eighteen letters from contributors, as well as four other letters relating to the publication of the Bow. Rawson’s scrapbooks were not a direct reflection of the printed version, but rather a record of the process of creating the gift book.

<26>The scrapbooks do not appear to have been used as a working copy for the Bow while Rawson compiled the volume. Rawson likely created the scrapbooks retrospectively, in the late 1850s or early 1860s, although she gleaned newspaper reviews and biographies and photographs over a much longer period. The boards and clasp of the Bow scrapbooks are very similar to another manuscript text she created: her handwritten “Memorials of James Montgomery.” Montgomery died in 1854, and based on references in her handwritten text, Rawson probably wrote this down between 1857 and 1862. The contents of the Bow scrapbooks – including newspaper reviews from 1834 and a newspaper obituary from 1848 – suggest that at least some of the contents were gleaned over a much longer period. This reflects that Rawson was engaged with these manuscripts over a sustained period between 1834 and 1862. The letters and contributions that Rawson received were kept in pristine condition and there is no evidence that she added editorial comments or revisions directly onto these original manuscripts.

<27>Rawson’s handwritten contents for the two scrapbooks are evidence that they were compiled by her, and that their organization today reflects her original ordering plan. The first is filled with those who contributed and the second with those who did not:

This volume contains the original manuscripts of the ‘Bow in the Cloud’ with portraits of the authors. M. A. R

This volume contains the portraits and autographs of those who declined to contribute to ‘The Bow in the Cloud’ and is filled with other anti-slavery letters (and papers) (pictures). M. A. R (Bow in the Cloud)

<28>As has already been noted, the scrapbooks contained poems that were more radical in terms of their depiction of slave insurrection than the printed gift book. Two poems that Rawson did not publish were “Toussaint Louverture” by Miss Ball and “The Reign of Terror” by James Everett. Everett sent his poem from Manchester on 14 June 1826, and it describes the bloody violence and vengeance that he predicted would be inflicted in the case of an uprising against those who held people in slavery in the West Indies. Specifically, it describes God’s vengeance on those in plantation societies who had inflicted a reign of terror over enslaved people. The description of the violent nature of this vengeance, “the voice of blood”, and the allusions to the French Revolution and the overthrow of authority in the poem contain echoes of slave insurrection. Miss Ball’s poem also describes the “negro-vengeance” and “deluge of blood” (BM manuscript poem 37). It celebrates and commemorates Toussaint Louverture, the leader of the only successful slave rebellion, which led to the creation of the free Black republic of Haiti. Ferguson believes that Rawson’s decision not to print a poem about Toussaint Louverture is reflective of her selection of conservative evangelical poems, which she suggests we might expect from Rawson’s Congregational faith. However, she overlooks that Rawson retained this poem within her manuscript scrapbooks (Ferguson 269 – 70). While this suggests that Rawson was conscious of her public image when it came to including radical poetry in her printed Bow with its wide and public audience, her decision to keep this in the manuscript scrapbooks seems to indicate that she did circulate this text amongst a smaller and more tightly controlled readership within her social network, which held more radical views.

Conclusion

<29>Rawson drew on traditions of women’s writing as well as the new and successful gift book form. Her Congregational religious identity was important in shaping the content and meanings of her gift book, her letters and her manuscript scrapbooks, and she included Congregationalist contributors who also played a role in her network. Both the printed gift book and the letters and scrapbooks were informed by the multiple traditions of Congregationalism and formed part of the literary culture and manuscript production and circulation that was central to women’s writing in the Romantic period. The letters also reveal the extent of collaboration between Rawson, Montgomery and Pringle, her publisher and Corbould, the contributors who supplied work, and those contacts who recommended her project to friends. Rawson used letters to connect herself to the male-dominated center of the London Anti-Slavery Society, through its secretary Thomas Pringle. For Rawson, letters and the project of compiling a collection of poetry and prose in the form of a feminine and sentimental gift book, allowed her to work with men and women abolitionists in a way that was unusual within the restrictive cultural ideals around women’s political activism.

<30>Rawson’s gift book, in print and manuscript form, demonstrates how manuscript production and circulation remained a vital political tool for abolitionist women writers in the early nineteenth century. Rather than a linear progression from manuscripts leading to print production, Rawson’s Bow blurs these lines and shows how manuscripts – valued in their own right – became printed texts that retained traces of their origins in letters and had a parallel life as scrapbooks. Scholars of abolitionism need to take far greater account of the resilience of manuscript culture and circulation amongst both men and women. When we approach women’s abolitionist campaign writing from this more expansive sense of their work, some of the divisions that we have created between women of different religious denominations begin to blur, and we see moments where what unites them – such as their shared sense of their campaign as well as their political methods – appears stronger than their differences. Given that we are learning how much contemporaries valued letter-writing culture and manuscript literary culture, it seems fitting to explore this culture and its meanings, and to use this as an opportunity to re-examine women’s political participation. The example of Rawson’s print and manuscript writing show a more radical and aggressive abolitionism which centers her more squarely in the vein of her contemporaries.

Acknowledgements: The research for this paper was carried out during a funded visiting research fellowship at the John Rylands Library, University of Manchester, March - May 2017. I am grateful to members of the BrANCH PG and ECR Workshop for providing insightful comments on an early version of this paper, at a workshop in August 2020.