<1>At the end of Sygurd Wiśniowski’s Tikera or Children of the Queen of Oceania, first published as Dzieci królowej Oceanii in serial and codex form in Warsaw in 1877, the unnamed Polish narrator encounters his erstwhile lover, the mixed-race Māori/British Tikera/Jenny, for the last time at Circular Quay in Sydney Harbour.(1) No longer a “half civilised” “child of Nature,” Tikera is now the wealthy and fashionably-dressed wife of a French doctor as well as mother to a pretty “quadroon” or “metis” child (Wiśniowski 82, 144, 287). The point of this meeting in a literal and symbolic hub of imperial transits and intersections is ostensibly to contrast French and British colonial attitudes to race and miscegenation: after years of failing to settle in Melbourne and Sydney because of “Anglo-Saxon racial prejudices” (144), Tikera and her family are emigrating to the creolized French colony of Martinique where mixed bloodlines are more acceptable. Anticipating Tikera’s favorable reception in a place already swarming with “Negroes and hideous mulattos” (291), the novel’s closing scene gestures towards the possibility of a solidarity (of sorts) across races, genders, and cultures, with Tikera extending to the narrator her “out-stretched, friendly hand” in a final act of affiliation and forgiveness: “A new thread of sympathy joined our hearts. I felt friendlier towards her than ever before, an exile recognized an exile” (291-2).

<2>The white sentimental politics of recognition the narrator identifies here is more than just an affective sense of shared exilic subjectivity. Once sexually aggressive and emotionally unstable, Tikera has now been resocialized in monogamous privatized intimacy and bourgeois family life by a “loving teacher” (144), her French husband Abrabat—a white doctor whose surname hints at his own possible Algerian or Moroccan racial intermixture. If she still cannot pass as white or European, Tikera is nonetheless representative of the set of “ideal relations” that define privatized heterocouplehood, including “coupling, procreation, and homemaking” (Rifkin, Straight 4, 7). It is her immersion and co-participation within the heteronormative family unit, and her transformation from sexualized lover to “modest matron,” that declares her fit for the rights and privileges of imperial citizenship: “Even half-wild Tikera, with her fiery eyes … became equal in love and discretion with a modest matron of our world” (144). Through her marriage to a white man (or one who passes as white), the narrator finally recognizes Tikera as “paradigmatically ‘human,’” with whiteness taken as “the universal model of humanity” (Rifkin, Straight 4; Crawford xviii).

<3>Drawing on the insights provided by scholarship on colonial biopolitics and queer Indigenous studies, and building on the idea of queer studies as a “subjectless” critique that has “no fixed political referent” (Eng et al. 3), this article considers how Tikera—and the archive of nineteenth-century settler fiction from Australia and New Zealand more generally—positions Indigenous, mixed-race, and minority peoples as queer to heteronormative settler colonial regimes. Its primary concern is not, therefore, so much with the growing body of work on gendered imperial ideologies of home and domesticity as with representations in settler fiction of precarious political subjects, such as convicts, indentured laborers, mixed-race peoples, and Indigenous peoples, as well as with how these “queer” populations function within the colonial imaginary. More specifically, I focus on how Tikera queers mixed-race Māori/British bodies and communal Māori kinship structures within the generic form of the imperial romance by representing them as incompatible with heteronormativity and the kind of love based on “a separated sphere of (privatized) intimacy” (Rifkin, Straight 96).

<4>At the same time, the novel is markedly more anti-imperialist in tone than other imperial romances of the same time period, with the narrator drawing parallels between his own state of political exile and that of the Māori people he encounters in Aotearoa New Zealand: “I come from a nation which would help you if it could … If you had any chance at all, I would encourage you to fight” (69). As these lines suggest, Tikera is set during, and was written just after, a protracted series of conflicts with Māori on the North Island from the 1840s to the early 1870s, thereby foregrounding questions of land tenure, dispossession, and the violence of British imperial expansionism.(2) As an exile whose homeland is under occupation by Prussia, Habsburg Austria, and Russia, the narrator expresses an ambivalent attitude towards western European imperialism, condemning the confiscation of Māori land authorized by the Settlements Act of 1863 and presciently critiquing the British settler colonial state as a rapacious and eliminationist system of dispossession, resource extraction, and capital accumulation that “destroys to create,” making “a desert out of a living country” before implanting “a new life there” (272).

<5>Recognizing both the incredible “success” of Anglo-Saxon expansionism and its enormous damage to local peoples and environments, the narrator’s anti-imperialist subject position disrupts the proto-nationalist impulses normally aligned with the imperial romance: unlike novels that depict cross-racial conjugality as a threat to the “territorial identity of the nation” (Rifkin, Straight 81), here the political union forged by Tikera’s marriage to Abrabat is one that supports a creolized imperial system, where citizenship and governance is rooted in a biological and affective identity that is never racially pure. In foregrounding the dynamics of racial creolization and, in particular, the transoceanic hybridization of Frenchness, Tikera, I suggest, is both a test and a limit case for the genre of the imperial romance. Despite its ostensibly anti-imperial politics, Tikera’s eventual conformity within the bounds of sentimentalized heteronormative domesticity is aligned with reproductive whiteness and ultimately with the elimination of Māori as a race. The crossing of the racial color line critiques the racialized territorial identity of the British national state only to deny the possibility of sovereignty or nation statehood to Māori.

Heteronormativity, biopolitics, and settler colonialism

<6>Heteronormativity, as Mark Rifkin has noted, “is a key part of the grammar of the settler state,” involving a cluster of connected issues such as “family formation, homemaking, private propertyholding, and the allocation of citizenship” (Straight 37). Rifkin’s work demonstrates how policies aimed at assimilating Native American Indians figured kinship structures as other than heteronormative, ensuring the queering and detribalizing of Indigenous peoples, and the breaking of intergenerational ties and traditional modes of territorialization, as well as introducing gender differentials in cultures where there were none (Lugones 196). In the context of colonial Australia and New Zealand, Patrick Wolfe, Damon Ieremia Salesa, Angela Wanhalla, and others have recognized the extent to which the settler colonial “logic of elimination” involves not just frontier homicide but also “officially encouraged miscegenation, the breaking-down of native title into alienable individual freeholds, native citizenship, child abduction, religious conversion, resocialization in total institutions such as missions or boarding schools, and a whole range of cognate biocultural assimilations” (Wolfe 388). As Salesa and Wanhalla have shown, interracial marriage was not prohibited by law in New Zealand, and racial crossings were encouraged by colonial officials as “part of the broader philosophy of racial amalgamation” that aimed to supplant Māori custom, language, kinship systems, and land tenure “via everyday opportunities for social and sexual intercourse” (Wanhalla 48; Salesa 31).(3)

<7>State-sanctioned intermarriage has increasingly been acknowledged as a “foundational technology” of settler colonialism, one that dilutes “traditional lineages,” promotes “migration away from ancestral lands,” and works as “a key force in the fragmentation of long-established social formations” (Ballantyne and Burton 7). Thinking through the processes specific to settler colonialism, Scott Lauria Morgensen argues that the strategy of elimination through assimilation and amalgamation requires a resituating of Michel Foucault and Giorgio Agamben’s work on biopower within “a new genealogy” (52, 53; see also Svirsky and Bignall). (4) For Agamben, modern sovereignty “depends upon generating a vision of the body” that is “cast as simultaneously exterior to the sphere of government and law” and as “the aspirational and normative horizon of political action” (Rifkin, ‘Indigenizing Agamben’ 92). As Rifkin points out, Agamben’s idea of “bare life” enables “the consignment of those who do not fit the idealized ‘biopolitical body’ to a ‘zone’ outside of political participation and the regular working of the law but still within in the ambit of state power” (92). The “people,” then, are those who exemplify the ideal body and will “consequently be recognized as citizens” while the rest are “consigned to the realm of ‘bare life’” (93).

<8>Agamben’s theoretical apparatus has been accused of naturalizing settler colonialism (Dietrich), but his work on the originary “state of exception” and the figure of homo sacer can be productively applied to illuminate how Indigenous peoples are eliminated in a state of exception to western law, a theory that can explain their “seemingly contradictory incorporation within and excision from the body of white settler nations.” Western law, as Morgensen points out, “incorporates Indigenous peoples into the settler nation by simultaneously pursing their elimination” (52, 53). Arguing that it is impossible to think of “biopolitics without geopolitics” or “bare life without bare habitance,” Rifkin traces in Agamben’s theorizing of the “body of the people” a concurrent “geopolitical project of defining the territory of the nation,” linking questions of bodily reproduction and sexual habitation to the “(re)production and naturalization of national space,” which in settler colonial states “depends on coding Native peoples and land as an exception” (‘Indigenizing Agamben’ 94, 95).

<9>Following Rifkin, Morgensen, and other scholars who consider the operation of biopower in the settler colonial context, I understand the representation of mixed-race and Indigenous peoples in Tikera as revealing of both the biopolitics of modern sexuality and the geopolitics of settler colonial expansion, regulating and replacing Indigenous sexual and gender norms with European understandings of heteronormative couplehood and privatized intimacy, while simultaneously removing Indigenous peoples from their land by establishing their existence as “bare life” within the settler colonial system. I consider, too, how various forms of sovereign violence require and sometimes even compel Indigenous peoples to accept forms of white recognition and “recognisable status under the law,” including ones that leave them open to elimination and replacement by settler rule (Morgensen 64, 65).

<10>Drawing on Morgensen’s argument that the need to “denaturalise settler colonialism” requires “concerted critique at the intersections of Indigenous and settler colonial studies” (52), I suggest that queer theory has a specific role to play in the analysis of Australasian settler fiction—one that goes beyond studies of the antipodal, uncanny, and/or gothic nature of settlement, and is able to address the naturalizing discourses of white heteronormativity that further the formation and perpetuation of the settler colonial state with its genocidal logics of white supremacy and heteropatriarchy. Ideologically, the queering of Indigenous, mixed-race, and minority cultures by white European settlers is regulatory rather than liberatory in intent and effect (Puar), but it is nonetheless important to consider the ways in which “ontologized subjects” at the centre represent those lying constituently outside the established moral and social order, as well as seeking to render whiteness and heterosexuality “visible to critical scrutiny” (Chambers and O’Rourke 4, 6; Johnson 5).

Queer mixed-race bodies

<11>While admiring the “statuesque proportions and fine features” exhibited by mixed-race peoples in Australia and New Zealand, and seeing them as superior to “a much frailer European stock,” the narrator initially considers a fellow Pole’s sexual preference for the “full figures” of “dusky Māori girls” as a “perversity in taste” (89, xxvi). If he increasingly acknowledges the “wellformed” attractions of “hard-working Māori maidens” (55), the mixed-race Tikera/Jenny is nonetheless represented as an aberrant or queer deviation from both Māori and European aesthetic, social, and gender norms. “[C]olossal” in scale (82) and with “exaggerated dimensions” (269), she is compared to “strange exotic” and “gigantic bronze monuments” (227, 158), as well as being characterized by unfeminine strength and the masculine “build of a prize-fighter” (184): “It seemed as if she did not lift her body from the ground as ordinary mortals do, but shot up from the bowels of the earth” (68). Unlike the French doctor Jenny eventually marries, who brings with him a creolized aesthetic and sexual taste cultivated in the former French colony of Louisiana, the narrator codes Jenny’s giganticism as unnatural, deviant, and transgressive, as a “manly” transgression of colonial racial and gender norms (143, 273). If he is too genteel to explicitly relate her size to an overdevelopment of the clitoris or labia common to European representations of the hypersexualized “black venus” (Gilman), Jenny’s oversized body is meant to signify a biologically determined sexual and emotional excess founded in unnatural and unfeminine desires.

<12>The narrator’s construction of Jenny’s mixed-race body as hyper-sexual, permissive, and “close to nature” pits her against domesticated and refined European women,; for example, her rival in love Arabella Whittmore, a blonde, chaste, and slender figure of Victorian womanhood, and the impoverished yet racially proud Irish girls (178), who fear the “taint” accompanying the “atavistic power of Māori heritage” (Moffat, “Belonging” 174). It also positions her in contrast to “docile” Māori women, who accept their “husband’s brutality with an almost dog-like devotion” (143), projecting the narrator’s sense that the affective bonds of sentimentalized domesticity are non-existent within Māori sexual and kinship relationships.(5) Jenny’s Māori lover, Te Ti (or George Sunray), for example, stands outside the emotional economy of Māori kinship structures because of his (Europeanized) sentimentalized attachment to Jenny. A sublime figure of virile heterosexuality cast in a decidedly heroic “last of his race” mold (22, 146), Te Ti is the only Māori character to be endowed with deep privatized feeling, although his attraction to Jenny is also attributed to the privileged status afforded to her by her light skin tone.

<13>Until the narrator’s belated concession that he was mistaken in attributing the ungovernable passion of “coloured women” to their inheritance or temperament rather than their upbringing (144), Jenny’s emotional and sexual excess is represented as part of a heredity that she can neither manage nor control. She is a global creolized “type” “often found in Oceania, Australia, the Rocky Mountains, or the flamboyant cities of the North American south,” for whom a European lover represents “the key to the wonderful white world which half-castes cannot otherwise enter” (143). Signifying the chaotic borderlessness that accompanies racial intermixture, Jenny-as-type feels both too much and too little: she is unable to defer gratification or to regulate her “irrepressible outburst[s] of passion” (76), but she also lacks emotional depth or substance, callously and unfeelingly substituting one white man for another without any lasting or durable bonds of emotional intimacy: “She simply wanted a pakeha for her lover, and I happened to be handy” (82).

<14>Despite his admission that Jenny is modest and until her relationship with the minor German aristocrat Charles von Schaeffer probably chaste, the narrator’s representation of Jenny draws on circulating narratives that Māori and mixed-race women were sexually promiscuous, and that Māori-Pākehā relationships, particularly on frontiers, were “transactional, impoverished of ceremony and lacking affection” (Wanhalla 22). As Wanhalla has shown, Māori-Pākehā interracial relationships, while expressing a whole range of motivations and affections, were, in fact, usually monogamous and, encouraged by missionaries, often concluded in Christian marriage ceremonies. Yet Jenny is represented in the novel as inherently unable to “belong to the national household/family,” whether Māori or European (Rifkin, Straight 39). Brought up on “the primitive love stories” of her Māori mother’s relationship with her white father, she is occasionally capable of tenderness and motherly impulses (see, e.g., 96), but the “European example” has given “birth to an ambition” in her for privatized intimacy that cannot “change her lusty nature” or provide her with faculties “her people do not possess” (143).(6) “Torn from her natural surroundings,” where “circumstances would have shaped her into the docile plaything of a savage,” Jenny is the “easy prey” of “white scum” who take advantage of her passionate but shallow nature (143), with the narrator admitting the scale of sexual exploitation across settler colonial spaces: “Practically every settler takes advantage of these ill-starred and gullible girls” (76).

<15>Attributing to intimate relationships a set of qualities usually associated with questions of sovereignty, Jenny’s ambition or desire for privatized intimacy is deeply entangled with the universalist rights-based conditions of legal equality required for liberal imperial citizenship. According to the narrator, her desire is for a partnership “in which two partners have the same rights” and in which “she expects to find love, chivalry, and equality” (143). If the implication is that Māori interpersonal relationships lack these attributes, the novel’s larger point is to disavow the possibility of Indigenous sovereignty by queering Māori homemaking, kinship structures, and forms of governance. Māori lack the capacity for the kinds of companionate and compassionate feeling that “provide the basis of affective nationality” (Rifkin, Straight 80). Uncoupling love and marriage, Jenny’s desire for legal and social equality is not dependent on deep romantic attachment or genuine emotions, and her pathologized mixed-race sexuality is constructed as outside of European norms of love, romance, marriage, and family: to the “white scum” that prey on her she is not worthy of the emotional labor of love or commitment.

<16>The narrator nervously recognizes the extent to which Jenny reduces the white man to his most substitutive and instrumental, and engages in a trade in “false feeling” that re-enacts the proprietary logic and rapacious speculative transactionism of settler colonial society with its policies of land-grabbing and resource extraction (Smith 10). This false trade is most obviously represented in the novel by Jenny relationship with Schaeffer, who sees her as a source of “ready money” for his fraudulent oil schemes (143). Jenny’s response to his financial and emotional betrayal is to ask about his contractual obligations under British law: “Doesn’t your law protect me? Why shouldn’t it take care of the daughter of a Black Kumara when it guards the golden-haired daughter of the Governor?” (180). As a “half-caste,” Jenny knows that she lies outside the social and political, if not the legal, matrix afforded to the status of citizen, just as Te Ti knows that his good character and testimony will “count for nothing” under a white judge (22). At times, Jenny seems to relish her status as outsider, auto-exoticizing her misplaced passions as outside British laws—“We rely on our strength. We don’t need your protection or your law. I can defend myself and take vengeance if I am deceived” (180)—but her state of exception is clearly represented as a defining feature and practice of the settler colonial state. As Schaeffer succinctly puts it: “Conditions in this country cannot be measured by a European yardstick” (187).

Romancing docile bodies

<17>In The Empire of Love (2006), Elizabeth Povinelli argues that “[t]he intimate couple is a key transfer point between, on the one hand, liberal imaginaries of contractual economics, politics and sociality and, on the other, liberal forms of power” (16). In the social logic of liberalism, love or romance is an “intimate event” that represents individual freedom over any kind of collective “illiberal, tribal, customary, and ancestral love” (Rifkin, Straight 11; Povinelli 226); in other words, the “autological subject” is contrasted with the “genealogical subject” (Rifkin, Straight 10). Jenny’s role in the novel is to demonstrate the mixed-race heroine’s transformation from genealogical to autological subject. To some extent, she is part of the formulaic triangular relationship between European traveller and Māori male figure that Terry Goldie identifies in his comparative study of the indigene, representing “the attractions of the land … in a form which seems to request domination” (65). But Jenny is also unusual in actively denying her Māori heritage and thus her connection to the land that is being repossessed. In this sense, she troubles and even obstructs the workings of desire structurally encoded within the form of the imperial romance. Her attraction to the white European male is not sexual but rather symbolizes her removal from the communal bonds of kinship associated with her kāinga: she despises her Māori relatives and is in turn despised by them as the child of a “Pokerakahu” or “Black Kumara” mother (89); that is, a descendent of a racial group with dark skin or African bloodlines (Petrie).

<18>Despite his English-language education, neo-classical beauty, and bodily vigor, Te Ti is unable to make a similar transformation from genealogical to autological subject because of the immutability of his Māori bloodline—a racialized essence that continues to define him despite attempts by British settlers to cultivate his assimilation within the settler colonial state. Already “marked for death” as a member of a “dying race” (Stoler, Education 144), Te Ti occupies a space outside of modern temporality by virtue of his projected and actual passing: “Below us we still heard … the chant of the bard over the corpse of the last chief of an ancient family. What more fitting De profundis than this tribal rite over a tribal hero?” (171). That Jenny does not choose “death” with Te Ti (who dies fighting for his tribal land following her rejection) but rather “life” with Schaeffer is a sign of her desire to align herself with the political and social bonds of white heteronormative couplehood. Acknowledging that she does not “want to be just a Maori girl” (136), her desire is essentially to efface communal Indigenous kinship alliances that represent “bare life” through the affective bonds of white privatized intimacy.

<19>Jenny’s father, too, is desirous of a clean break with Māori. Described as belonging to “the dregs of the colonial community” (71), Williams is a former convict who has escaped from a penal settlement and lived as a fugitive among Māori, as well as working as a seaman in the Pacific and as a wandering, unsettled gold prospector (89). Williams’s past is suggestive of a dark history of cross-cultural sexual exploitation on the margins of colonial society, but as a wealthy settled farmer now living outside the kāinga, he sees a fundamental disjunction between his (unstable) whiteness and Māori modes of household and sovereign formation. If Williams, unlike Jenny, cannot be rehabilitated or resocialized within a creolized imperial society—his homosocial obsession with Jenny’s abandonment (an abandonment that mirrors his own rejection of her mother) and his almost single-minded death-drive ends in his final “mortal embrace” with Schaeffer (285)—his fantasy is nonetheless for a form of order that will assure the stability and coherence of his and his daughter’s identity as white.

<20>As Ann Laura Stoler has pointed out, European legal status for those of mixed parentage required both displays of “familiarity and proficiency with European cultural styles” and “proofs of estrangement” from Indigenous life, especially the feeling of being “distanced” from “that native part of one’s being” and “of feeling no longer at home in a native milieu” (“Affective States” 7). Politically speaking, Jenny’s disaffection with her native ties and her desire for the psychic and bodily wholeness represented by the untainted bloodline is a desire for the wholeness of the universal subject associated with western subjectivity, with the novel enacting and encoding the logic that the Indigenous subject always desires the universality of the western subject. The process of Jenny’s acquisition of universality involves a re-schooling of the chaotic energies that define her as an ethnographic type. Yet her Europeanization or naturalization into imperial citizenship is also represented as a process marked by comic inauthenticity. In her relationship with Schaeffer, she is elaborately but grotesquely pimped in crinoline, unaware that she is modelling the louche, leisured lifestyle of a European mistress rather than the role of wife within a Christian Protestant model of domesticity (184). The sexualized Jenny must later be “re-schooled” by the “discipline of an elegant environment” (270). Ironically, this re-schooling by the French Abrabat is not so much to rid her of remnant Māori traits or customs, but rather of the English affectations of her “white sisters,” which detract from the “natural feeling for beauty” associated with pre-contact Māori (271).

<21>The same acquisition of inauthentic universalism is evident in Wiśniowski’s representation of Māori Christian teachers, missionaries, and pastors. In the first of the novel’s two captivity narratives, the narrator’s captor is a wealthy mission-trained teacher, who lives “in true European style” (62). The Christian village in which the narrator is held captive is ostensibly one in which Māori customs have already died out. The narrator attends an Anglican religious service, but while the melodic harmonies of Māori-language hymns initially seem symbolic of the triumph of civilization and “right feeling” over “cannibal orgies” (79), the whole service, like Jenny’s Europeanization and Schaeffer’s oil schemes, is revealed to be sham: “It was stupid to suppose that twenty-five years of civilization had eradicated the vengeful and cruel customs which had been practised for well-nigh six centuries” (91). Having lost all sense of his authentic Māori identity, the “monstrous parson” is little more than a fraudulent “pseudo-Christian, who concealed his natural impulses behind his dog-collar” (91). The Indigenous experience of Christianity and conversion in New Zealand is represented by the narrator as hypocritical, false, and performative; and Māori Christian lay teachers, jealous of their white British church superiors, are declared the “root cause” and driving force behind the New Zealand Wars (87).

<22>Until the concluding chapter of the novel, the narrator repeatedly voices anxieties regarding creolization, conversion, assimilation, and cultural intermixture of all kinds, with the Europeanization of Māori represented as a force to be both desired and derided as inauthentic. Yet Jenny’s re-schooling cannot simply be a reversion to a “natural” pre-contact “state of grace” (271). Pregnant with the white Schaeffer’s child, she must be taught how to become a wife and mother, both in terms of acquiring an idealized sense of nurturing motherhood and in terms of being groomed for maximum productivity within settler colonial society. The docile bodies of the Māori women in the kāinga are ultimately not dissimilar to the docile bodies of European women required for reproductive labor and domestic life, but Jenny must also be taught certain cultural competencies and emotional standards; in particular, she must be taught to feel discriminately, proportionately, and in a manner directed towards the objects of marriage and family. While we are not privy to the details of her resocialization, the process involves a coercive pedagogic transformation of those affective bonds that will authenticate her as a wife and legitimate imperial citizen.

Transits of exilic subjection

<23>The novel’s closing scene depicts Tikera’s intimate enclosure within the heteronormative family unit tied by the durable bonds of “affective self-sufficiency” (Rifkin, Straight 79). Knowing that her child is, in fact, the illegitimate daughter of the now-deceased Schaeffer does not diminish the extent to which the transgressive energies of the once aberrant Jenny have been contained within heteropatriarchal imperial structures. Tikera’s reproductive position is ultimately in the service of the colonizers since Indigenous inhabitancy is coded as a force that disables the settler colonial polity and indigeneity is erased through intermixture with whiteness. Marriage to a white man involves not just the reification of heteronormative authority, assuaging to some extent white anxieties regarding eugenics, breeding, and mixed-blood races through an officially sanctioned miscegenation, but also guarantees a future entailing the assimilation and hence the elimination of Māori as a race.

<24>Since in much settler writing the nuclear family is a “vehicle through which to represent the determinate coherence of the nation” (Rifkin, Straight 79), as well as a means to assert the various forms of imagined indigeneity that underwrite settler subjectivity, it is perhaps unsurprising that interracial conjugal union requires Tikera to leave her homeland. There is no sense that Tikera’s French husband can become “native” to Australia or New Zealand or that Tikera herself can properly find a “home” within the British settler colonial state; nor do the captivity narratives involving the Polish narrator and the German Schaeffer offer “alchemies of white transformation (into indigeneity)” (Simpson 108). On the surface, the novel’s final scene in Sydney Harbour suggests that Māori society can be renewed by creolization, but the equation of “liberation with leaving and oppression with ‘staying put’” often associated with the diasporic subject is almost completely absent from the novel’s final scene (Gopinath 92).(7)

<25>Jodi A. Byrd has considered the ways in which indigeneity functions as a transit in the settler colonial state, by which she means “to be in motion, to exist liminally in the ungrievable spaces of suspicion and unintelligibility.” As she puts it, “to be in transit is to be made to move” (xv). Like the narrator who has “swung between the poles … in search of new places and new people … no man’s friend, an unwanted citizen” (107), Tikera’s removal from Oceania is a forced removal, an exile from a homeland that she finally realizes is tied to her very personhood. While she appreciates intellectually that the move will guarantee her acceptance in the French colonial public sphere, Tikera notes that “it won’t be my own country. A daughter of the pearl of the Antilles would be able to find true happiness there, but not I, for I am from the pearl of Oceania” (291). Acknowledging for the first time her profound connection to the land in which she was born and her ties to Māori culture and tradition, Tikera recognizes the reality of her Indigenous personhood, an identity rooted in her Oceanic lineage and symbolized by the re-adoption of her tribal name: “My daughter and I shall always be proud of our Maori name” (290).

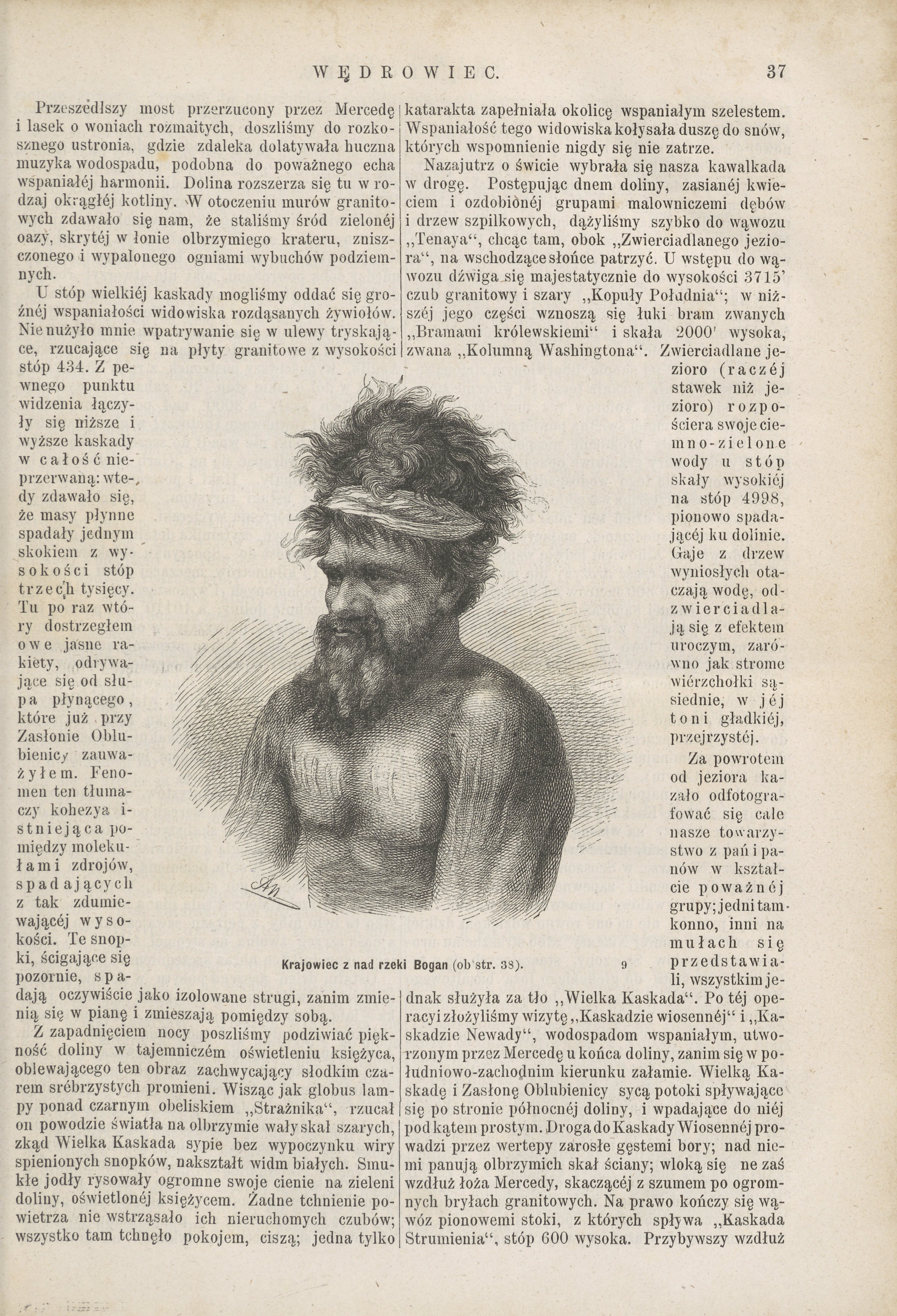

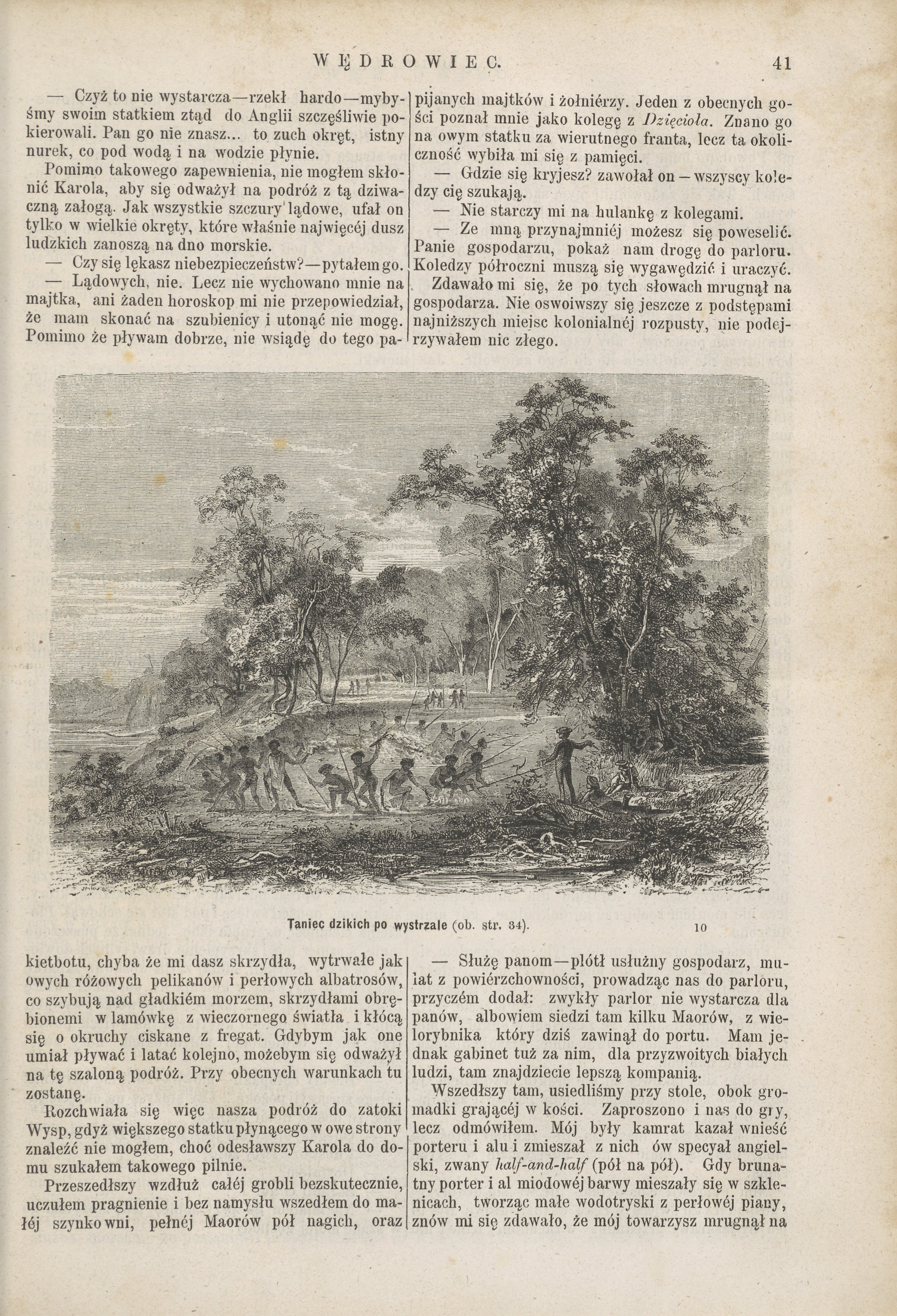

<26>Tikera’s profound grief and regret troubles any liberatory sense of an exilic subjectivity potentially to be found within the creolized space of Martinique or in the liquidity of oceanic travel. While Tikera is finally able to recognize and grieve the loss of her homeland and Indigenous identity, the “pose of the exile” the novel deploys draws on the trope of the “abject indigene,” simultaneously doomed and in need of civilization, thereby representing the double-bind of Indigenous survivability: Tikera’s survival depends both on leaving New Zealand, where Māori, the novel suggests, will be wiped off the earth, and on intermarriage with a white man, which will eventually erase Māori blood-lines. Prised from the debased local attachments of her Indigenous homeland and body, Tikera now recognizes herself as an inhabitant of a queer space and time, living in limbo among the dead and slowly dying: like Te Ti who is “no longer alive,” Tikera is described as “no longer alive either, for she had been transformed into an entirely different person” (290). A chastened, de-eroticized Tikera knows that she has been marked for death by heteronormative filiation: she is to be absorbed into the imperial body politic and settler nation through the patriline and the marriage contract.

<27>The point of the novel is not, therefore, simply to showcase what constitutes an ideal creolized imperial citizenship, but also to mark the disappearance of Māori as a historical and political force following the end of three decades of frontier conflict in colonial New Zealand. As in historical novels by Walter Scott and James Fenimore Cooper, the (proto-)nation comes into being and consolidates itself via the combined experience of war and capitalist modernization. While notionally immersed in the logics of reproduction, labor, and capital accumulation (Tikera and her husband will run a plantation equipped with slaves in Martinique), Tikera is marked for death; she is quite literally what Byrd calls “the living dead of empire” within the “necropolitical” settler colonial state (Byrd 226; Mbembe 11). The final pages of the novel are predictably elegiac in tone, with Tikera noting that her daughter must be made worthy of those “noble people whose blood may flow in her children’s veins on a far-away tropical island when everyone in New Zealand will have forgotten what the Maori people even looked like!” (290).

<28>The slow death of Māori is anticipated in the novel’s preface, where a fatalistic framework represents the novel’s work as proleptic salvage ethnography: Māori are said to be “dying out like the snow in spring, melting away unresistingly” and “peacefully dying” (xxvi). This transmutation of the realities of violent death via war, disease, and extermination into “a strange peace” (xxvi) is reminiscent of Charles Darwin’s belief in the natural “displacement” of Indigenous peoples (Barta 20-41), placing the novel within scientific and ethnographic discourses naturalizing genocide. The novel’s ethnographic sub-text is further reinforced by its serialized publication in the Polish illustrated weekly magazine Wędrowiec or Wanderer (est. 1863).(8) One of Joseph Conrad’s favorite boyhood magazines, Wędrowiec was based on the French weekly travel journal Le Tour du Monde (est. 1860), and in the years 1863-1883 specialized in entertaining and popular science, geography, travel and exploration, history and world culture, and technology, including reprints of articles on French, British, and German ethnographic expeditions (Kamisińska).

<29>Although Tikera was written on Wiśniowski’s farm near New Ulm, Minnesota between 1874 and 1876, it was published alongside profiles of the Polish zoologist Szymon Syrski’s travels to east Asia; maps, etchings, and articles on Tunisia and Tunisian life; articles on Greek antiquities; and Wiśnowski’s own Dzicy w Australii (1877), as well as being interspersed with ethnographic etchings of Indigenous peoples (Fig. 1) and customs (Fig. 2).(9) The serialization of the novel in a magazine that specialized in ethnographic and scientific discourses reinforces a sense of its representation of Māori as a “species” marked for death and further qualifies its apparently anti-imperialist politics. On the one hand, Tikera is critical of the British expansionist project: the wars on the North Island are wars “of conquest” (264) designed to rob Māori of their land in favour of “a few grasping speculators” (23), and the narrator explicitly links oil schemes and other forms of extraction to the dispossession and extermination of Māori, as well as to a longer history of resource depletion, environmental damage, and species extinction (103-4). On the other hand, the novel’s focus on the dynamics of the intimate private sphere works to assimilate Indigenous and mixed-race peoples within settler conceptions of marriage, love, desire, and family, denigrating Māori kinship structures as unfeeling and uncivilized. Even the narrator’s sympathy for Tikera, as the “poor creature” and “naive savage girl” exploited by others (143), functions, as Amit Rai has argued, as a technology and modality of white imperial power, objectifying and transforming Tikera from a half-wild mixed-race girl to a compassionate imperial citizen (Rai 3).

Queering the imperial romance

<30>Tikera was published only in Polish in the nineteenth century, making it an imperial romance about a British settler colonial state in which “nationality, ethnicity, and language of writing and subject matter” are not neatly synchronized (Maxwell and Trumpner 107). This remove from the generic expectations of an Anglophone reading audience amounted to an opportunity to rethink the conventions of the imperial romance from within a particular set of historical and political circumstances. Poland in the 1860s and 1870s was still experiencing a period of national struggle in response to occupation by the Prussian, Austrian, and Russian Empires, including several failed uprisings in 1831, 1846, 1848, and 1863. While never explicitly stated, the narrator’s forced exile is likely to have been part of the exodus of Poles after the failed 1863 uprising. Tikera therefore offers a rare example of Polish exilic self-representation within a nineteenth-century British settler colonial state, a “peculiar insider-outsider” perspective that in many ways veers from seeing the Pole as a doomed exilic figure of “moral uprightness” and “sacrifice” (symbolized in the novel by the Prussian General Tempski) to the unsettled and morally ambiguous nature of the narrator, who describes himself as an “undoubted radical” and “neither wholly good nor wholly bad” (Maxwell and Trumpner 107; McLean 155; Wiśniowski 144, 107).

<31>As a Pole, the narrator’s qualified whiteness ensures him a degree of acceptance in British colonial society, but he is nonetheless a perpetual wanderer, traveller, and exile from his native Poland, who can never quite acclimatize in the liminal, frontier spaces he visits in foreign lands. The novel therefore represents a more realistic version of the “melancholy travels of the fictional Romantic outsider” (McLean 170): life as a European immigrant in a British colony is described as akin to the life of a criminal, who “generally hides his origins, often assumes a fictitious name, and seldom makes a hasty confession of his past” (11). The narrator and Schaeffer are treated as second-class citizens by “conceited,” “puritanical,” and “hypocritical” British settlers (101, 121), who maintain their “superiority over all others, even Europeans” (262). Described as a “stubborn utopian” (188), the narrator at times appears proud of his Romantic Polish heritage, but his itinerant lifestyle and his self-styled radicalism increasingly trouble that idealization. In this sense, the narrator is a progenitor of what Renata Ingbrant has called the “New Man” in fin de siècle Polish fiction: that is, a model of masculinity that challenges traditional gender roles and seems insufficiently heroic or domestic (130). In this case, Wiśniowski takes the Polish “New Man,” and his disenchantment with the myths, traditions, and idealisms of the “old world” in Poland, and resituates him in the “new world” of colonial New Zealand.

<32>Wiśniowski draws, too, on the formal and stylistic conventions of the Polish gawęda to provide the impression of the novel’s “unmediated orality” (Gasyna 156), suggesting the closeness between Tikera and the travel memoir formula of his Dzicy w Australii (or Ten Years in Australia) published alongside each other in Wędrowiec. Catherine Leach describes the gawęda as a form that blends textual styles and genres—such as elements of the epic, the picaresque, the chivalric romance, the campaign tale, the chronicle, the diary, and the memoir—as well as foregrounding the narrator’s sense of accumulating wisdom via unfamiliar or exotic experiences (lvi). Although the narrator in Tikera is a more sophisticated version of the often-naive protagonists of the traditional gawęda, the novel certainly follows the gawęda in its complex intermixture of genres and in its centring of the “autobiographical hero,” who “performs a triple function as author, narrator, and main hero” (lviii).

<33>Yet while the novel draws on the gawęda and on the familiar tropes of Polish Romanticism—in particular, on a “preoccupation with lost causes and with the loss of honor by betrayal” (Gillon 434)—the nationalist aspirations of those tropes are repeatedly deflated or de-realized by the narrator’s critiques of British nationalism/expansionism, his own removal from the site of Poland’s struggles, and the impossibility of nation statehood for Māori. Indeed, the novel’s persistent deflation of the tropes of the Polish Romantic tradition coupled with the narrator’s quixotism means that, like Joseph Conrad’s work, it is a darker revision of the imperial romance. Schaeffer, for example, resembles the (often minor) aristocratic protagonists of the imperial romance but with a difference: he is overtly venal, deceptive, grasping, speculative, and morally bankrupt, bringing to the surface what is usually supressed in the romance form (Moffat, “Five Imperial Adventures” 57). While the narrator’s reflections in Tikera by no means amount to the kind of extended existential self-enquiry undertaken by Conrad’s protagonists, he nonetheless resists self-enclosure within British imperialist systems of resource extraction and capitalist accumulation, identifying not as a settler but as a nomadic wanderer, who undergoes a kind of moral and spiritual education.

<34>Unlike the classic bildungsromans of nineteenth-century metropolitan and settler fiction, however, the narrator fails to reach his “maturation by domesticating itinerant (false) tendencies” (Marzec 132), instead recognizing his own internalization of “Anglo-Saxon racial prejudices” (144) as a moral failing and holding up the creolized French Empire as a more ethical version of imperialism. By the end of the novel, it is the British Arabella (rather than Tikera) who seems to the narrator “prouder than a planter’s wife, as ungovernable in her passions as the hurricanes of her Island, sensitive and intractable in the extreme” (262). Now conflating slave-owning and racial prejudice (rather than race) with emotional ungovernability, the narrator’s moral arc involves a radical rethinking of biological and racial heredity even as he continues to conjoin interracial conjugality with the assimilatory regimes and disciplinary structures of the settler colonial state.

<35>Uneasily straddling the generic features of the imperial romance, bildungsroman, and gawęda, the tropes of Polish Romanticism, and the seriality of periodical fiction, Tikera’s complex formal and structural intermixtures exist alongside a stylistic and thematic oscillation between realism and romance—in particular, a continual oscillation between the eroticization of Māori as a “doomed” or “dying” race and a more realistic, unchivalric vision of the sexual and political exploitation at the heart of that eroticism. The novel thus submerges romance prototypes within a geopolitical reality that distinguishes it from the period’s mass-culture adventure stories. It is this mismatch between its historical material and its romance mode, I suggest, that makes Tikera an early example of those late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century “outland geographic novels” described by Richard Maxwell and Katie Trumpner as pushing “beyond existing norms of cultural description, avoiding exoticism and expanding the spatial boundaries of the Victorian world,” as well as typically straddling “the boundary between fictional and documentary writing” (106). As Maxwell and Trumpner argue, the geographic novels of the late nineteenth century essentially transformed the historical novels of Scott and Cooper into a spatialized and “highly self-conscious form of global writing” underwritten by a “new transcultural model of authorship” (107).

<36>My point here is not to claim Tikera as an anti-imperialist text: on the contrary, its reliance on the discourse of salvage ethnography, its privileging of the regulatory heteronormative family unit, and its naturalization of “the heterosexual Native woman’s desire for a white man” all work together to encode “conquest as a universal love story” (Finley 36). Yet Tikera offers something more than what Wendy Katz calls “a logical congeniality with messianic interpretations of Empire and with notions of ruling class stability” found in imperial romances by Rider Haggard and others (Katz 34; see also Caserio), instead exposing the racial, sexual, and other structural inequalities on which interracial love stories rest. In its representation of Jenny’s failed love affairs but most especially in her successful marriage, Tikera demonstrates the extent to which love and intimacy, too often depoliticized, are in fact central to biopolitical and structural violences such as legal discrimination, sexual exploitation, material dispossession, and enforced removal. This does not make the novel anti-imperial in any easy sense but it does queer the imperial romance as a genre and form, unravelling the nationalist logic of the quest romance in a favour of the more conflicted and ambiguous impulses of the creolized exilic figure moving between liminal spaces within a transimperial world-system.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the European Research Council under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 679436). Images from Wędrowiec are from the Digital Library of the University of Lodz: Biblioteka Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego.