<1>Pamela Colman Smith (1878–1951) was an artist, writer, editor, folklorist, and publisher whose transnational career began during the late-Victorian period. Smith spent her childhood in England and Jamaica before moving to New York at the age of 15 to study Art at the Pratt Institute. During the course of her career, she illustrated more than twenty books, wrote numerous articles, and served as editor of two little magazines in London (O'Connor, “Pamela's Life” 11). Her illustrative works featured marginalized figures, women, magic, and Caribbean folklore. Smith was an unconventional figure when she emerged on to the London publishing scene in the late 1890s. Socially, she was a racially ambiguous, unmarried and career-driven woman with interests in the occult. She defied nearly every Victorian convention of gender and class. Professionally, Smith rejected the over-industrialized British mass media market and utilized a hand-colouring technique as well as an arts-and-crafts mode of production in her illustrative works. In many of her collaborative projects with male colleagues throughout her life, Smith’s work and contributions were discounted or undervalued. The negative experiences she dealt with in the male-dominated late-Victorian publishing industry were likely what motivated her to found her own magazine, The Green Sheaf (1903–4), and subsequently The Green Sheaf Press (1904–6). Launching these ventures enabled her to have more control over the publishing process. As was typical with periodicals of the fin-de-siècle period, the back of each issue of the The Green Sheaf magazine contained an advertisements section featuring forthcoming books, other magazines, and local artisanal businesses. The remarkable aspect of The Green Sheaf's advertisement section is how much of the advertising space is reserved for fellow women and gender non-conforming entrepreneurs.

<2>The pages of The Green Sheaf featured a network of literary and artistic figures who published “pictures, verses, ballads of love and war; tales of pirates and the sea” (Smith, The Green Sheaf, no.1, 8). The contents of The Green Sheaf are quite balanced between textual and visual content, but the magazine’s illustrations are a stand out as many of them received a meticulous hand-colouring treatment. Issues of The Green Sheaf were between eight to sixteen pages in length and occasionally in the shorter issues featured supplements (Kooistra, “A Paper of Her Own”). Given the smaller scale of the little magazine, it is remarkable that at least one or two pages of each issue were devoted to advertisements. Smith’s choice to do so demonstrates her commitment to promoting the products and services of the individuals within her personal and professional networks. The transnational roster of contributors meant the little magazine reflected a wealth of interests and topics. Several individuals associated with the Irish revival movement made contributions to the magazine, including artist and wood engraver Elinor Monsell (1879–1954) and writer Lady August Gregory (1852–1932). Monsell’s artwork “The Book-worm” and Gregory’s translation of “The Hill of Heart’s Desire” by Irish poet Anthony Raferty (1779–1835),are the two pieces that open the first issue of the magazine (Kooistra, “Critical Introduction to The Green Sheaf, no. 1”). Electing to feature the work of these two particular figures not only aligns the magazine with the Irish revival movement, but also unequivocally demonstrates Smith’s commitment to featuring the creative works of women authors and artists. Other topics explored in The Green Sheaf included mysticism, works from the past, and stories from overseas. In addition to editing the magazine, Smith made illustrative and literary contributions to each issue. Single copies of the little magazine could be obtained for thirteen pence, or an annual subscription to the magazine could be purchased for thirteen shillings. The Green Sheaf had a limited print run but could be purchased from vendors in England and The United States. This included Charles Elkin Mathews’ Vigo Street book shop in London and, after the seventh issue, copies of the little magazine were sold at Brentano’s Bookstore in New York. After the fourth issue, Smith began selling copies of The Green Sheaf out of her flat in London (Kooistra, “A Paper of her own”). In her role as editor, Smith was described as “an indefatigable worker, enthusiastic and rapid” by an unnamed reviewer for The Reader (“Writers and Readers” 331–332). In his review for The Academy and Literature, William Teignmouth Shore (1865–1932) similarly praised Smith’s contributions in what he referred to as “strange little periodical,” claiming her designs for The Green Sheaf were “by far the best” (307). Undoubtedly, Smith’s magazine stood out as a unique publication on the British media market.

<3>At the back of almost every issue, Smith promoted herself and her various business ventures, including hand-coloured stationery and performative storytelling of West Indian folktales, while also showcasing the labor of other businesswomen. Contributing to a growing body of research focused on recovering Smith's life and work, this article demonstrates how Smith used the advertising pages of The Green Sheaf as a material method of promoting the work of marginalized creators and authors within the late-Victorian period. I will begin by briefly summarizing Smith’s business background leading up to the creation of The Green Sheaf to illustrate how the difficulties she experienced within the male-dominated publishing industry motivated her choice to create a space to showcase her fellow women and gender non-conforming authors and entrepreneurs. I will then analyze The Green Sheaf advertisements; the marketing tactics used to promote these women-operated businesses; and the vast social, political, and professional networks and movements connected to these individuals and their businesses. Ultimately, Smith’s advertisements section was focused on showcasing the creative and technical labor of a group of women who were connected to the publication and its editor, more so than as a method to develop revenue for the magazine. While the biographies of some of these women contributors and entrepreneurs may be unknown, their professional endeavors are nonetheless preserved within the pages of The Green Sheaf.

<4>In 1895 Smith enrolled in the Pratt Institute and studied under artist Arthur Wesley Dow (1857–1922). Smith did not complete her studies and left the art school after two years, but it was during this time that she was able to secure her first commission. Another Pratt student, Earnest Elmo Calkins (1868–1964), paid Smith US$10 for an illustration of one of Aesop’s fables, The Crow and The Pitcher (Calkins 169; O'Connor, “Pamela’s Life” 21). Coincidentally, this turned out to be Smith’s first brush with the advertising industry. Calkins, a night school student, was also a copywriter who helped establish an art department at Charles Austin Bate’s (1866–1936) advertising agency (Calkins 166–167). Calkins was given the “authority to buy work from outside artists for special purposes” and regarded Smith as a clever individual who produced illustrations that possessed a “quaint simplicity and charm” (Calkins 169). This commission led to other jobs solicited by Calkins and an evolving friendship between the two. In 1897 and at only 19 years old, Smith was invited to exhibit her work at William Macbeth’s (1851–1917) gallery in New York. At this exhibition, she sold four watercolour paintings and regularly sold prints, illustrations, and Christmas cards through the gallery until the end of the year (O’Connor, “Pamela’s Life” 22–23). For the next few years, Smith was kept busy with travel and commissions, including an illustrative advertisement for the Christmas Book Buyer, which was featured on the cover. In 1899, Smith’s career began to flourish. Aside from publishing several illustrative projects, including The Golden Vanity and The Green Bed, she produced her first book-length work. Annancy Stories, an illustrated collection of folklore she heard during her childhood in Jamaica, was also published by E. H. Russell in 1899 (O’Connor, “Pamela’s Life” 27).

<5>In 1900, Smith moved to England, escorted by British actor Ellen Terry (1847–1928), with whom she had become acquainted in New York when the actor was on tour with fellow actor Henry Irving (1838–1905) and the Lyceum Theatre troupe (Cockin, “Pamela Colman Smith, Anansi and the Child” 73). The early success Smith had found for her creative labor and book projects in America did not follow her across the Atlantic to England. After settling in London, she regularly wrote to friends and colleagues to divulge her poor experiences with the city’s publishing houses. She complained about her lack of success in finding a publisher for her proposed illustrated editions of Anna Barbauld and William Blake in a letter from March 1901 to author and friend Alfred Bigelow Paine (1861–1937) she wrote: “Pigs! The publishers are all pigs!?!” (qtd in O’Connor, “Pamela’s Life” 44). When her work was published or purchased, she was often forced to negotiate and was underpaid for her labor. Her designs for the now-famous Rider-Waite-Smith tarot deck, which she was commissioned to produce in 1909 by Arthur Edward Waite, was a large-scale job that paid “very little cash” (qtd in O’Connor, “Pamela’s life” 74). Additionally, Smith only recently received recognition for having designed the tarot deck, despite its international popularity (Greer 371). Even towards the end of her career, Smith could not support herself financially through her various entrepreneurial ventures and artistic creations. In 1927, Smith wrote to art dealer and author Martin Birnbaum (1862–1967) to ask if he knew “of someone who [would] buy some drawings” as she was in dire need of money (qtd in O’Connor, “Pamela’s life” 88). In that same year, Smith reached out to friend and costume designer Edith Craig (1869–1947) to ask if she would assist in selling some of her artwork. As Smith described to Craig, “I am badly in need of money just now. I have sold nothing this year” (qtd in O’Connor, “Pamela’s life” 88). Certainly, Smith’s struggles with finances and her inability to secure stable work were a lifelong plight.

<6>Smith’s connection to Terry proved integral to her early work in London. She began working on several collaborative projects with Terry’s daughter, Edith Craig, and Craig’s long-term partner, Christopher St John (1871–1960), both of whom would be featured later in the advertisements section of Smith’s The Green Sheaf. Smith was also commissioned for tours with the Lyceum Theatre company, where Terry worked as an actor (O’Connor, “Pamela’s Life” 41–42). However, despite the creative opportunities she was able to generate through Terry’s familial, social, and professional circles, Smith was unable to secure stable income for herself. Over the course of their friendship, Terry recognized Smith’s undervalued talent as an artist and creator in the British mass media market. Terry demonstrates this understanding in her correspondence to her son, Edward Gordon Craig (1872–1966), where she describes Smith to be “extraordinarily industrious & is ever-lastingly making & selling as fast as she makes” (qtd in O’Connor, “Pamela’s Life” 40). Similar to Smith, Edward Gordon Craig worked as an illustrator, amongst other ventures, but their respective treatments in the various male-dominated creative industries were vastly different. Despite Smith’s entrepreneurial spirit, demonstrated talent, and work ethic, her work was not adequately compensated. In a subsequent letter to Edward Gordon Craig, Terry notes, “Pamela Smith doesn’t get paid nearly as well as you, & she doesn’t lose patience” (qtd in O’Connor, “Becoming Pixie” 96). Terry’s comment not only identifies the pay gap between men and women during the fin-de-siècle period, but hints at the lack of privilege and security Smith held as a woman artist. In comparison to Edward Gordon Craig, Smith may have been forced to self-monitor her behavior out of fear of being dismissed as an amateur.

<7>Smith’s motivations to create her own magazine seem to emerge from her professional experiences with men. In 1902, Smith joined Jack B. Yeats (1871–1957) as co-editor of A Broad Sheet, a one-page publication that featured hand-coloured drawings; a monthly subscription could be obtained for twelve shillings a year. Her tenure at the magazine lasted one year, during which time she had become allegedly overwhelmed by the magnitude of hand-colouring that fell on her shoulders for each issue (Cockin, “Pamela Colman Smith, Anansi and the Child” 74). While Yeats’s sister, Lily, would visit Smith in her studio once a month to help with the massive task of hand-colouring the issues of A Broad Sheet, it seems that Lily Yeats’s assistance might have been more traumatizing than helpful on occasion. Lily Yeats described Smith as often being fatigued during these sessions and sometimes even being driven to tears by Lily’s incitement to work, despite her obvious exhaustion. Elizabeth O’Connor suggests that Lily’s testimony of this recurring situation does not reflect how much time, if any at all, Jack Yeats spent colouring the Broad Sheet issues himself and that Lily’s interpretation does not seem to reflect sympathy for Smith’s increased workload as a result of additional creative projects she was undertaking (“Becoming Pixie” 115). A letter from Jack Yeats to a colleague, John Quin, hints at a touch of contention between the two editors during their work:

Between you and me and the wall, as they say, Miss Pamela Smith (though I think her a fine illustrator with a fine eye for colour and just the artist for illuminating verse) is a bit lazy, and she being a woman I can’t take a very high hand with things, so there is often a lot of fuss about the numbers, and I don’t like to be responsible for anything that I have not got absolute control over. (qtd in O’Connor, “Pamela’s Life” 46)

Though Smith and Jack Yeats’s working relationship may have been difficult at times while they were co-editing A Broad Sheet, Yeats contributed an illustration for an untitled poem in the tenth issue of The Green Sheaf. Additionally, A Broad Sheet was featured in the advertisements section of the second, third, and fifth issues of The Green Sheaf.

<8>In 1903, Smith left her role as co-editor of A Broad Sheet to found The Green Sheaf, publishing 13 monthly issues between 1903 and 1904. The little magazine was printed on hand-made paper and, similar to A Broad Sheet, utilized hand-colouring in its production. Smith used the magazine as an opportunity to print some of the work she had not been able to publish when she moved to London, including an illustrated version of Lessons for Children, written by Anna Barbauld (O’Connor, “Pamela’s Life” 44). Smith’s full-colour illustrations depicting scenes from Barbauld’s text appear in issues four, nine, and thirteen of The Green Sheaf. Smith’s belief that The Green Sheaf could provide her with a steady income seems to diminish over the course of the magazine’s life. On the back of a supplement included in the ninth issue, Smith wrote a note to her readership to alert them that after the thirteenth issue the magazine would only be published quarterly, indicating that the magazine was either a lot of work or becoming quite costly to produce at monthly intervals (Supplement Advertisements). In February 1904, Smith wrote to Paine to inform him that the magazine would likely move from a monthly publication to twice a year. She cited the need to scale back the number of issues annually due to wanting to allocate her focus to other projects, including her performative storytelling of West Indian Folklore, which she hoped would generate some income for her. She added, “Green Sheaf does not pay yet—It is most discouraging to go on working at it” (qtd in O’Connor, “Pamela’s Life” 55). Despite not serving as a reliable source of income for Smith, The Green Sheaf did provide her with an opportunity to establish herself within the British publishing market.

<9>In addition to her own works, Smith published poems, short works, and illustrations produced by a roster of literary and artistic women and gender non-conforming figures from the Victorian era. Approximately thirty per cent of The Green Sheaf’s authors and illustrators were women or gender non-conforming figures, many of whom contributed to the magazine multiple times. A common thread amongst these contributors is that many were hardly recognized during their time for their literary or artistic efforts. Edith Craig’s partner, Christopher St John(1) (1871–1960), was a gender-non-conforming writer and playwright whose work was featured in issues one, two, three, six, and eight of The Green Sheaf. While they were only featured once across the magazine’s advertisements section, in a half-page piece in issue five advertising the contributions of the next issue, this is likely due to the fact that the bulk of the work published in their name was completed in the period of time after The Green Sheaf stopped printing. During the late-Victorian period, St John served as the ghostwriter for Ellen Terry, who was one of the most renowned Shakespeare actors to have emerged during the nineteenth century. St John penned texts like Terry’s autobiography and The Russian Ballet, a book that was illustrated by Smith and described some of Russia’s most prolific ballet dancers and dances. St John also wrote many of Terry’s speeches, including a feminist lecture series on Shakespeare’s heroines, which was internationally disseminated. This lecture series was later assembled into a book published in 1932 entitled Four Lectures on Shakespeare. The publication of this lecture series followed Terry’s death, and in the introduction to the book, St John notes that they served as her “literary henchman” and was hired for “all occasions when she had to write something for publication, make a speech, or give an interview” from the period of 1903, the same year The Green Sheaf was founded, until her death (St John 8). Evidently, Smith’s magazine served as an opportunity for St John to publish under their own name during the publication’s short life.

<10>Two of the most frequent contributors to the magazine include artist and writer Dorothy P. Ward (1879–1969) and author Alix Egerton (1870–1932). Two elements of Ward’s signature style make her illustrations for issues two, four, seven, eleven, and thirteen stand out amongst the other artistic contributions to the magazine. First, for most of the illustrations she contributed, there was a textual paring and title incorporated into the image itself. For instance, in her contribution “Too Early to Bed—A Lament,” Ward sandwiched the visual element of the work between the title at the top and poetic component at the bottom, just underneath where the praying angels are sat on the floor in front of the bed of the child (The Green Sheaf, no. 2 14). Second, Ward is significant for her ability to design an image’s frame as a decorative component for a picture’s contents. Ward’s illustrations for “Evening” in issue four, “Autumn” for issue seven, and “The Changed World” for issue eleven all featured branches or vines as the frame of the images, sometimes weaving in or around the other visual or textual elements of the pieces. Furthermore, the outline for her untitled illustration for issue thirteen of The Green Sheaf mirrored the bubbles that the small child was blowing at the fish within the image (Ward “Untitled” 2). Egerton regularly contributes poetic pieces to the magazine and is featured in issues one, four, five, seven, eight, nine, twelve, and thirteen. Both Ward and Egerton published outside of The Green Sheaf but, despite this, there is still very little available biographical information pertaining to either of them. Egerton, for instance, published more than twenty works during her career, including The Lady of the Scarlet Shoes and other Verses in 1903. Smith included a portion of this text in the October 1902 issue of A Broad Sheet and promoted the book in an advertisement featured in issues 7 through 11 of The Green Sheaf. Unfortunately, the absence of well-maintained biographical histories for Ward and Egerton is an issue that affects a number of women contributors featured in The Green Sheaf. This includes writer Lucilla, who contributed “At Departing” in issue two and “A Sonnet” to issue four of the magazine. Similarly, poet Lina Martson (1866– ?) contributed a piece entitled “Donald Dubh” to the magazine’s third issue, but little is known about Martson outside of her membership to the Masquers Society. This theatre society “combined symbolic sets and historical costuming,” which Smith and The Green Sheaf contributors, musician Martin Shaw (1875–1958), Christopher St John, Edward Gordon Craig, poet William Butler Yeats (1865–1939) were also a part of (Kooistra “Critical Introduction to The Green Sheaf no. 3”). Eleanor Vicocq Ward (1889–1976) contributed two pieces to the magazine—a poem entitled “Autumn” for her sister Dorothy P. Ward’s illustrative contribution to issue seven and a set of poems, entitled “Arcadian Songs”, in the final issue—but little data regarding her biographical or career history exist. Unfortunately, much of the personal and professional histories of other women contributors featured in this magazine are absent from the historical record, resulting in a gap in scholarship that fails to recognize the impact of women on the literary and cultural scenes in London at the turn of the century. There are digital projects, such as the Yellow Nineties Personography, which are actively working to restore the forgotten histories of women contributors like the ones mentioned here, but it is inevitable that some of these records are unrecoverable. In a mass publishing market saturated with male authors, Smith’s The Green Sheaf served as a haven for women to feature their creative work and assert their autonomy in a market that marginalized their contributions. As I will now discuss in detail, Smith’s promotion of women’s labor in the primary literary and artistic sections of The Green Sheaf was similarly reflected in the magazine’s advertisements section as well.

Analyzing The Green Sheaf’s Advertisements

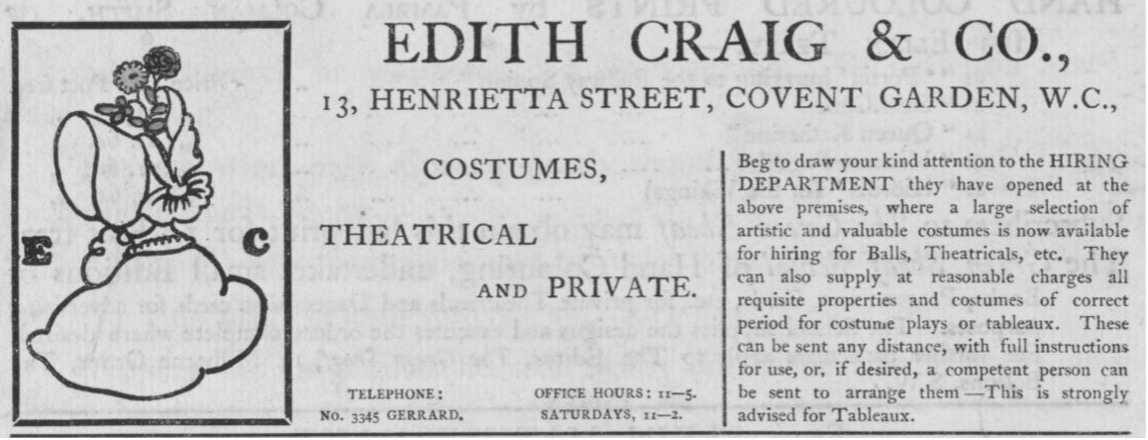

<11>The advertisements section of The Green Sheaf demonstrates an effort to illuminate women’s work and their contributions to the British economy while also challenging the established divisions of class, gender, and labor present at the turn of the century. The Green Sheaf is one of many little magazines from the fin-de-siècle period that began to appropriate advertising tactics, such as including illustrations, found in the late-Victorian mass marketing press. While some magazines used advertisements to offset publishing costs, Hélène Védrine notes that there are cases where a magazine and the business being advertised engaged in an opportunity for mutual sponsorship in lieu of charging that business a cost to advertise in the magazine (90). There could be instances of this in The Green Sheaf, one of them being an advertisement for John Baillie’s (1866–1926) gallery at 1 Princes Terrace in London. In 1903, Baillie designed a series of exhibitions that would showcase “neglected artists” (“Mr John Baillie’s Gallery” 11). Smith was featured in this series, where she exhibited a collection of water-colour drawings at the gallery alongside Claude Hayes (1852–1922) and The Green Sheaf contributor Cecil French (1879–1953) in November 1903 (“Fine Art Gossip” 658). While Smith was promoting Baillie’s gallery, Baillie was simultaneously promoting and selling Smith’s artistic works. Smith’s surviving correspondence to a few of the entrepreneurs and writers featured in the advertisements section, including Edith Craig and Christopher St John, made no reference to the cost, if any, to advertise their products or businesses in The Green Sheaf . Additionally, The Green Sheaf did not publicly display opportunities for authors or entrepreneurs outside of her coterie to advertise their products or services in the magazine, indicating that Smith’s social networks generated The Green Sheaf’s advertisements section. Simply put, The Green Sheaf’s advertisements section seems less concerned with generating revenue from selling advertisement space and more with propagating and making visible products, labor, and businesses associated with marginalized individuals. As Lorraine Janzen Kooistra notes, “Smith understood that advertisements were a means of networking producers and consumers” (“A Paper of Her Own”). Smith edited her magazine to serve as a feminist material object that showcases the creative labor of women and gender non-conforming figures, and the advertisements section demonstrates a similar editorial method to reflect Smith’s social and political agenda. The next section of the essay will analyze the materiality of the advertisements and demonstrate their embodiment of Smith’s support for women’s entrepreneurship in the marketplace.

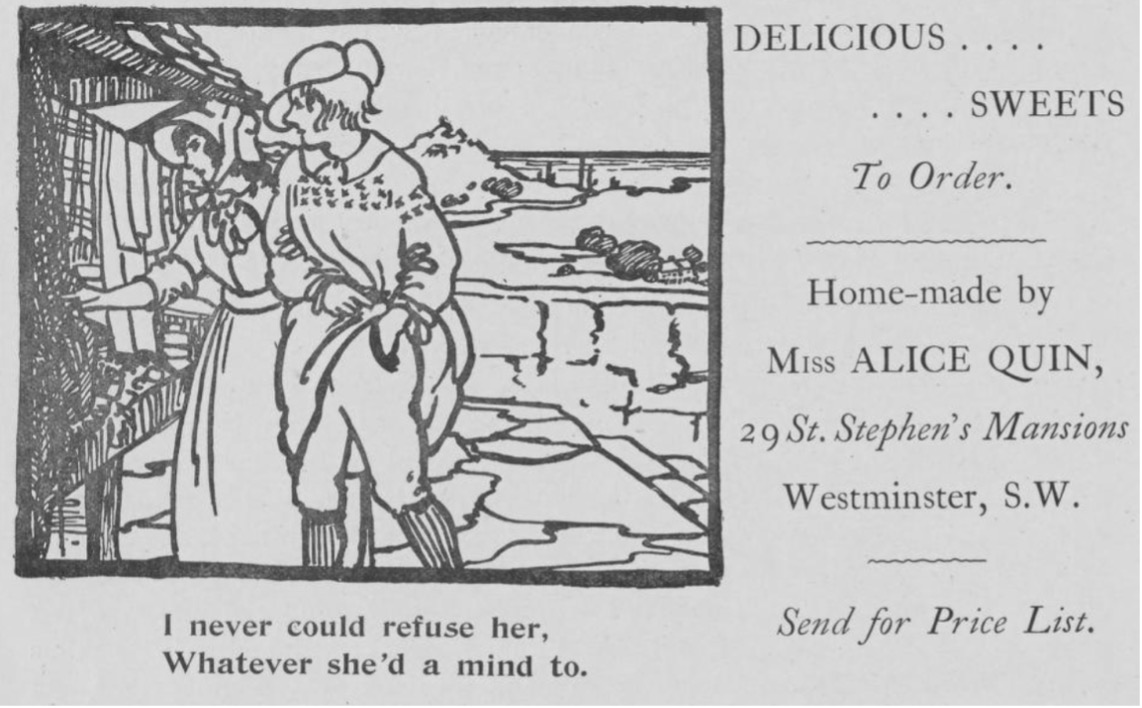

<12>Of the 158 advertisements for businesses, objects, or books across the thirteen issues of The Green Sheaf, almost half of the advertisements explicitly recognize the labor of women and gender non-conforming individuals. However, rather than simply making this type of labor visible by giving accreditation to the advertising entrepreneur, Smith designed and constructed the advertisements section so that it placed greater visual emphasis on the advertisements by marginalized figures. My methodology for analyzing the material elements of the advertisements present in The Green Sheaf focuses on five core elements: size, style, components, placement, and recurrence. The combination and use of these elements alludes to Smith’s implicit signal of support for the creator, product, or services. The size of the advertisement, or how much physical space within a page the advertisement occupies, indicates implied value by the editor. The style of the advertisement identifies the components that work to make the advertisement eye-catching. Stylistic choices for an advertisement’s visual portion could include the use of hand-colouring, framing, white space, capitalizations, different typefaces, emboldening, or other artistic decorations. Components refer to additional information that is included in an advertisement outside of the service, business, or product name, the entrepreneur or creator name, the price of the product or service, and the address of the business. Additional components consist of elements such as illustrations and reviews from other magazines or periodicals. The placement of the advertisement in relation to others in the section helps determine the visibility of the advertisement. For example, advertisements that bookend the section are more likely to be seen as opposed to those buried within a list. Lastly, recurrence looks at the frequency in which an advertisement or entrepreneur appears across the magazine’s various issues. Multiple occurrences of an advertisement could indicate Smith’s ongoing support of that business.

<13>Smith designed and structured the advertisements section to centralize written works and creative labor by women and other marginalized creators. By far the largest advertisements in The Green Sheaf are the products and services associated with women’s labor. For instance, in issues two, three, four, five, and six, Smith included an advertisement for future issues of The Green Sheaf featuring some of the artistic and literary contributors, including women and gender non-conforming individuals, to be expected in upcoming issues. This advertisement is typically situated at the very end of the advertisements section, likely because Smith wanted the advertisement to have a lasting impression on the readership. This block of text typically takes up about half of a page and the names of the contributors are all capitalized to increase visibility of their names. Notably, Smith’s name at the bottom of the advertisement is in a larger font size than the other contributors listed in the advertisement, likely to draw attention to her role as editor. Another prominent advertisement is one for Edith Craig’s costume business, which appears in the first five issues of the little magazine (Figure 1). Each advertisement for Craig’s business in The Green Sheaf takes up about one-third of the overall page. The left third of the advertisement is an illustrative component depicting a large bonnet with two flowers, typically hand-coloured red and yellow, sitting atop the bonnet and at the base is a cape that appears to be wrapped around or resting on someone’s shoulders. In all capital letters, at the top right of the advertisement is the business name, “EDITH CRAIG & CO.” Notably, this is the largest font used in any advertisement across all issues of the magazine. Beneath this is Craig’s business address and two columns: the one in the centre of the advertisement which displays the wares on offer—“Costumes, Theatrical, and Private”—in three asymmetrical lines, while the column at the right provides further details about Craig’s rental and consulting business (Smith, “Advertisement for Edith Craig & Co”). The image is one of two advertisements that is hand-coloured across the issues of the magazine, the other being a singularly occurring advertisement for Smith’s West Indian Folklore storytelling service (Figure 2). There are a few instances, notably in the first and third issues, where yellow washes have been applied to the outside of the bonnet, which makes the advertisement pop against the beige, hand-made paper. The variance of text size, capitalization, and placement are powerful stylistic choices that also make Craig’s advertisement stand out on the magazine’s page. The frequency in which this advertisement appears through the magazine’s life is likely due to Smith’s close personal and professional relationship with Craig, which was highlighted earlier in this paper.

<14>By far, the most stylised advertisements that Smith designed across The Green Sheaf issues are the ones associated with women’s work, likely in an attempt to highlight their efforts. In fact, the only businesses with illustrations are those associated with women’s work. Aside from Craig’s advertisements, Smith incorporated her illustrations in the advertisements of the businesses of Miss Alice Quin, Mrs. Fortescue and herself. The image Smith used for Miss Alice Quin’s advertisement for baked goods in issue nine was an image that appeared previously in full colour in A Broad Sheet (Smith, “All Round my Hat”). The text underneath the black and white image in The Green Sheaf is two lines of All Around My Hat, a song that emerged in England in the 1820s. The abbreviated lines read, “I never could refuse her, Whatever she’d a mind to” (Figure 3) (Smith, “Advertisement for Delicious Sweets”). Both this song and image appeared previously in A Broad Sheet, and the typeface used for printing the song in The Green Sheafwas the same typeface that appeared in A Broad Sheet. The song is about a London-based produce seller who promises to stay true to his betrothed, a woman sentenced to several years in an Australian jail for theft. In the image for Quin’s advertisement, Smith depicted a man and woman walking through a marketplace. She holds onto his elbow with her right hand and appears to be reaching over to a stall to take some merchandise with her left hand. With his free hand, the man reaches into his pocket, likely to retrieve some coins to pay for the item the woman is interested in (Smith, “Advertisement for Delicious Sweets”). As the image and text are used in an advertisement for Alice Quin’s baked goods, the implication is that the woman in the image is reaching for a delicious pastry. Smith’s pairing of this image and segment of the text presents us with an alternate version of “All Around my Hat”, in which the man is able to provide items for his sweetheart so that she does not succumb to a life of crime. Smith’s image then also visualizes the marketplace consumption of goods from a woman-operated business for her readership.

<15>In addition to including illustrations in advertisements for women-operated businesses in order to highlight them within the advertisements section of The Green Sheaf, the magazine included additional textual components to some advertisements to make the particular product or service more appealing to her readership. This could take the form of reviews or testimonies, as is the case with The Season with the Poets, an anthology arranged by Ida Woodward, in issues eight, nine, ten, and eleven. Along with Woodward’s name, the title of the book, and the price, is a review from the Court Journal that explicitly references Woodward’s efforts; “The wideness of the range adds to the charm of the selections” (Smith, The Green Sheaf, no.9 12). An advertisement for Songs of Lucilla, by an unnamed author, appears in issue two, which includes a review from The Spectator that states, “The author of these verses shows a very considerable power of writing. She has not merely the accomplishments of style and melody, but a way of attacking her subject which shows real power…” (Smith, The Green Sheaf, no.2 17). Similar to a review, another component used in the advertisements section to promote women’s work was to list customers of note who were enjoying the product, to demonstrate active engagement of a woman-owned business in the Victorian marketplace. In issue twelve, Smith includes an advertisement in the upper right-hand corner for Isobel B. Quin’s frame-making business. Customers listed in the advertisement include Ellen Terry, Israel Zangwill, Irene Vanbrugh, Lady Alix Egerton and more (“Advertisement for Isobel B. Quin” 8). In this way, the advertisements in The Green Sheaf also served to establish the social networks that were at the heart of this magazine.

<16>By far, the entrepreneur with the most visible presence throughout The Green Sheaf advertisement pages is Smith herself. Smith advertises eight different types of services, products, or businesses she embarked on within The Green Sheaf’s advertisements section across numerous recurring advertisements. These advertisements promoted other little magazines, books, copies of illustrations or prints, lace designs, workshops, custom bookplates and holiday cards, and a performative story-telling service of West Indian folklore. The West Indian folklore performances advertisement claims to have been led by “Gelukiezanger”, the identity she used in her folklore service, who shared the same name as the Tiger character in her Annancy Stories (Figure 2). The advertisements for Smith’s various businesses show an ongoing attempt to integrate herself into the Victorian marketplace. Zoe Thomas argues that women business owners associated with the arts-and-crafts movement were more likely to “advertise flexibility in working across a wide range of fields” in an attempt to appeal to more people and secure steadier income for themselves” (187). Despite what appears to be a diverse portfolio of work advertised in the magazine, Smith’s artistic and technical labor could not sustain her financially.

The Magazine’s Political, Social, And Artistic Connections

<17>The remainder of this essay will analyze how the businesses reflected in The Green Sheaf’s advertisements section were concurrently engaged with a number of social, political, and artistic movements that were active during the publication of the magazine. Alongside advertising businesses that could appeal to the magazine’s particular readership, the construction of the advertisements section demonstrates the strategies and “alliances between artistic groups and movements” (Védrine 89–90). In conjunction with a demonstrated effort to support the works of women, the advertisements section of The Green Sheaf illustrates Smith’s connections to social and political movements that sought to challenge late-Victorian divisions of sex, labor, gender, and class, such as the Suffrage and arts-and-crafts movements. By highlighting creators who were followers or participants in these movements, Smith demonstrated her support for and connection to these movements.

<18>Several individuals in the advertisements section of The Green Sheaf were ardent supporters of the suffrage movement, including romantic partners Edith Craig and Christopher St John. The duo had memberships in numerous women’s societies, including the Women’s Social and Political Union, the Catholic Women’s Suffrage Society, and the Women Writers’ Suffrage League. Both Craig and St John contributed to a variety of suffrage plays, including How the Vote was Won and A Pageant of Great Women, to advocate for women’s rights at the turn of the century (Cockin, “Christopher St John”). Elizabeth Gibson (1869–1931) was a writer, poet, and typist who was similarly involved with the suffrage movement and featured in the advertisements section of The Green Sheaf. Gibson’s book of poems From a Cloister was featured in the advertisements section of the tenth and eleventh issues of The Green Sheaf. Additionally, an advertisement for Gibson’s book of carols entitled A Christmas Garland was included at the back of the eighth issue. The book featured drawings by Edith Calvert (1864–1938), wife of Charles Elkin Mathews (1851–1921). Gibson published over 40 books during her time but was ultimately overshadowed by the fame of her younger brother, Wilfrid Gibson (1878–1962), who was also a poet. Elizabeth Gibson was an active supporter of the suffrage movement and, similar to St John, published books with themes of lesbianism and female eroticism (Greenway 319–320). While there may be, and likely are, more women and gender non-conforming entrepreneurs in the advertisements section of The Green Sheaf associated with the suffrage movement, scholarship has failed to preserve the biographical histories of these individuals. Until they are uncovered, we are unable to know the true extent of the suffragist and queer networks existing in little magazines during this period. Smith was also a supporter of the suffrage movement. Following the production of The Green Sheaf, Smith became a member of Laurence and Clemence Housman’s Suffrage Atelier, an arts-and-crafts society dedicated to securing enfranchisement for women. Smith contributed posters and handbills during her time with the Atelier. However, the organization did not keep records of productions, so the exact number of items Smith contributed is unknown (O’Connor, “Pamela’s Life” 78). Smith’s inclusion of Gibson, St John, and Craig in The Green Sheaf’s advertisements section at the back of several issues of The Green Sheaf demonstrates an attempt to promote the creative and technical labor of feminist, queer women and gender non-conforming individuals, who greatly challenged expectations of gender and class at the turn of the century.

<19>The Green Sheaf’s advertisements section also highlights a few women entrepreneurs and creative laborers that were connected to the arts-and-crafts movement at the turn of the century. As a form of production, the arts-and-crafts movement was founded in reaction to growing societal reliance on industrialization and mass production. The movement challenged Victorian notions of class and labor and aimed to disrupt the traditional hierarchy of art forms, which valued fine arts paintings above craft forms such as jewelry making, leatherworking, or hand-colouring. During the fin-de-siècle period, women creators were often thought of as amateurs. Their artistic productions were typically regarded as non-professional, domestic activities or a hobby instead of a genuine profession (Thomas 155). Scholarship has traditionally focused on the arts-and-crafts movement primarily in relation to the male figures associated to the field, specifically concentrated to textile designer, writer, and artist William Morris (1834–1896), who was most commonly regarded as the founder of the movement. The focus on male creative labor meant that the labor of women participating in arts-and-crafts production was largely ignored. Feminist scholarship’s efforts to include women’s labor then shatters the male-centric and “traditional periodization of the Arts and Crafts movement” (Thomas 155). In the advertisements section of The Green Sheaf, Smith showcased women creators such as Elizabeth Corbet Yeats, one of the founders of the Dun Emer printing press. In 1901, two years before The Green Sheaf was founded, Smith was engaged with the Dun Emer Guild. Smith provided designs for a collection of objects for the guild, including book-plates and cards, and also offered advice on the hand-printing process (Kooistra, “A Paper of her Own”). An advertisement for a book produced by the Dun Emer hand-printing press, called In the Seven Woods by the founder’s brother, William Butler Yeats, appears in issues two and three. This advertisement explicitly names Elizabeth Yeats as the individual that assembled the book, highlighting her technical labor at the hand-printing press.

<20>Another woman entrepreneur showcased in the advertisements section of The Green Sheaf is Miss Baillie, who created hand-made lace and gave lessons on the craft. It is more than likely that Miss Baillie is connected to Gallerist John Baillie as they share a last name and have businesses listed with the same address throughout The Green Sheaf. John Baillie was born into a New Zealand family with four sisters: Louisa, Jessy, Elizabeth, and Rosa. The first three died by 1873, leaving Rosa Baillie as the most likely candidate for “Miss Baillie”. Smith’s guest book, which she used to have available for friends to sign at the creative salons she regularly hosted in her flat at 14, Milborne Grove between 1901–1905, shows signatures from a John Baillie and a “R Baillie,” reaffirming that Miss Baillie is most likely John Baillie’s sister, Rosa Baillie (Kaplan 149). Advertisements for Rosa Baillie’s lace-making services appear in issues 2 and 3 while advertisements for John Baillie’s gallery, which featured various forms of arts-and-crafts production, appear in issues four through twelve. Smith’s various advertisements for hand-coloured books, prints, and illustrations appear throughout the numerous issues of The Green Sheaf and demonstrate her connection to the arts-and-crafts movement.

<21>During the fin-de-siècle period, many arts-and-crafts movement followers attempted to assert themselves as professionals by advertising workshops available to the public. Thomas notes that “establishing a business, and in particular a workshop, played a critical role in the making of reputations” (159). John Baillie, Rosa Baillie, and Smith all participated in this late-Victorian trend by advertising workshops for their respective arts-and-crafts fields within the magazine’s pages. Rosa Baillie’s lessons for lace-making are advertised in numbers two and three. In issue four, Smith included an advertisement for the Green Sheaf School of Hand-colouring, which “undertakes small editions of books, programmes, cards, etc.” (Smith, The Green Sheaf, no.4 15). Elizabeth O’Connor notes that it might be possible that if there were any students enrolled in this school, they might have assisted in colouring The Green Sheaf’s illustrations as a part of their artistic training, although there exists no proof of this (54). All of John Baillie’s gallery advertisements in issues four to twelve include a list of workshops available through the gallery on different art forms such as “enamelling, metal-work, carving, bookcasing, water colours, fan painting, wood engraving, etc.” (“Advertisement for John Bailie’s Gallery” 16). In advertising these workshops, all three were attempting to assert a level of expertise that would distinguish them from amateur status. For Rosa Baillie and Smith specifically, asserting in print their professional status challenged the gendered expectations of women involved in the arts-and-crafts movement at the turn of the century.

Conclusion

<22>Although The Green Sheaf could not generate significant revenue for Pamela Colman Smith, the magazine served as an opportunity for women and gender non-conforming individuals in her social networks to attempt to promote their labor and professionalize their labor within the Victorian marketplace. Following the conclusion of The Green Sheaf, Smith, along with her friend Mrs. Fortescue, founded the Green Sheaf Press. This hand-printing press was the only business featured in a full-sized advertisement in The Green Sheaf’s publication history, included in supplement to the last issue of the magazine (Figure 4) (“Advertisement for the Green Sheaf Shop,” Knightsbridge). The press continued Smith’s quest to focus on promoting and supporting women writers’ efforts (O’Connor, “Pamela’s Life” 11). Smith kept the press running until 1906 and published a collection of folk and fairy tales, poems, and novels, including her own work (O’Connor, “Pamela’s Life” 58). Smith remains an artist, editor, and illustrator who is beginning to gain recognition as an influential force in the publishing and art scenes in London at the turn of the last century. Aside from her unique artistic praxis, her commitment to making visible the creative and technical labor of women and gender non-conforming individuals from her social circles will forever remain a fundamental component of her legacy as a creator during the fin-de-siècle period.