“The riches and greatness of Peru increase daily to such an extent that they become almost impossible to believe…like something from a dream.”

Licenciate Gaspar de Espinosa, Governor of Panamá, to Emperor Charles V (1535)

“It is his [Atapalipa] Indian Golde that indaungereth and disturbeth all the nations of Europe.”

Sir Walter Raleigh, The Discoverie of the Large, Rich and Bewtiful Empyre of Guiana (1596)

<1>Near the base of the Dauer Clock Tower at the University of Miami, nestled beneath a canopy of towering Cuban Royal Palms (Roystonea regia) and surrounded by groves of Malayan Coconut Palms (Cocos nocifera), Dominican Macaw Palms, (Acromia aculeata), Brazilian Buri Palms (Polyandrococos caudescens), Mascarenean Bottle Palms (Acromia aculeata), and the medicinal African Boundary Tree (Newbouldia laevis), lies a fresco of relief ceramic tiles whose deep cobalt hues reflect the waters of the Atlantic just a few miles away. Pictured in this patchwork of images, oftentimes moist to the touch in the humid and oppressive heat of South Florida, one espies the figures of two men emerging from the dense forest of plant species that surround them. Here, the libertador Simón Bolívar and the explorador Alexander von Humboldt stand together, their silhouettes facing towards the South American continent they had vowed to liberate from Spanish rule.(1)

<2>As I stand before Bolívar and Humboldt, in this, the gateway to the Americas, I feel the absence of the woman whose vibrant Parisian salon welcomed both men and fostered their transatlantic visions. She is Helen Maria Williams. Perhaps no other woman of the nineteenth century came to know more about South America and its topographic makeup than Williams. Her knowledge of the New Continent was forged from the ground up: from its schistose strata and columnar basalt to its plant geography of palm, fern-trees, and lichens, to its reptilian and mammalian species of crocodiles, fishes, and monkeys. After studying and translating thousands of manuscript pages of Humboldt’s Vues des Cordillères, et Monumens des peoples indigènes de l’Amérique (1814), and the Relation historique du Voyage aux régions équinoxiales du Nouveau Continent (1814-29),(2) Williams became more than a participant in the production of a Latin American literary culture in the 1800s; she was one of its chief exponents. Though Williams has long been recognized for her poignant eye-witness accounts of the French Revolution and her unwavering support of liberal causes, her transatlantic writings, namely Peru (1784), Paul and Virginia (1795), “Sonnet to the Curlew” (1796), “To the Strawberry” (1796), “To the Torrid Zone” (1796), “To the Calbassia Tree” (1796), “To the White Bird of the Tropic” (1796), Researches (1814), Personal Narrative (1814-29), and Peruvian Tales (1823) remain tangential rather than central to her legacy to British Romanticism.

<3>In this paper, I wish to explore this unfinished portrait of British literary history where Helen Maria Williams remains but a specter in our discussions of South America’s landscape, which during the late eighteenth century was deeply rooted in the politics of mining on the New Continent. Decades before her collaboration with Humboldt and her salon gatherings with Bolívar in Paris, Williams demonstrated an innate curiosity about the Andes and its rich mining historiography in one of her earliest compositions in England, the epic Peru, A Poem in Six Cantos (1784). Though scholarship of Peru has concentrated on examining the nexus between the peoples of the Iberian Peninsula, Britain, and the Inca Empire, a critical study of Peru, as place and mining space, has largely been neglected. To address this omission, I will examine how Peru functioned as an important pre-text to the Personal Narrative, producing what I call an ‘Andean aesthetic,’(3) or a structural tableau-like poetics where Williams could recreate climates, landscape topologies, and anthropological settings in ways that allowed British readers to organize and internalize the biodiversity of South America. To complement this reading, I will turn to Williams’s revision of Peru, the little-known Peruvian Tales of 1823, to show that by the early nineteenth century, the discourses of nature had become complicit with the South American mining boom of the 1810s and 1820s.

A World Beyond London

<4>At the age of 23, a young Helen Maria Williams fixed her gaze towards the west. Williams may have stood in London, but her Peru transported her across the Atlantic. Through a type of virtual voyage, she descended upon the South American continent like a worldly traveler. Ambitious in scope for a budding writer, Williams’s 1500 line, six-canto epic relating the fall of Perú was dedicated to Elizabeth Montagu (née Robinson) (1720-1800), whose bluestocking circle participated in its early circulation in manuscript form. Montagu’s lively salon at Portman Square influenced a generation of writers, including Williams, who opened Peru with a dedicatory poem thanking her for serving as a model of female patronage:

WHILE, bending at thy honour’d Shrine, the Muƒe

Pours, MONTAGU, to thee her votive ƒtrain,

Thy Heart will not her ƒimple notes refuƒe,

Or chill her timid ƒoul with cold diƒdain […]

Woman, pointing to thy finiƒhed Page,

Claims from imperious Man the Critic Wreathe. (iii, v) (4)

<5>From the beginning of her literary career, Williams always maintained a close association with a community of women writers including Hannah More, Anna Seward, Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Hester Lynch Thrale Piozzi, and Penelope Pennington. They would both support and critique her severely as she chronicled the Revolution in France. The correspondence of Hester Lynch Thrale Piozzi and Penelope Pennington reveals the extent to which Williams’s political voice was continually overshadowed by her personal affairs, which she vehemently sought to protect. Williams’s intimate, lifelong friendship with John Hurford Stone, Esq.(5) (1763-1818), a British reformer and London coal merchant, cast an even darker cloud on this period in her life. In a letter from Piozzi addressed to Pennington at Hot Wells, Bristol, on 17 February 1795, Piozzi wrote “The Rival Wits say that Helen Williams is turn’d to Stone, and tho’ she was once Second to nobody, she is now Second to his Wife, who it seems was not guillotined as once was reported; but remains a living spectatress of these Political and Impolitic Revolutions (PPC).”

<6>Early on, however, Williams, the “poetess,”(6) garnered a great deal of national praise from other women writers for her choice and treatment of the Andes. Elizabeth Ogilvy Benger’s (1778-1827) The Female Geniad (1791), for example, paid homage to her gift for historical narration since it brought the history and the woes of Perú to view, allowing one to “feel their sorrows, weep their fate anew.” “Tuneful Williams,” Benger wrote, has unveiled at last “these scenes of devastation past.” Anna Seward’s “Sonnet, to Miss Williams, On her Epic Poem PERU” published in The London Magazine of 1785 commended her as a Poetic Sister who had “seiz’d the epic lyre — with art divine” to “hymn the fate of a disastrous land.” Seward, Benger, and their contemporaries would have been well-acquainted with Upper and Lower Perú (modern day Perú and Bolivia) by reading such diverse geopolitical representations of the Andes as François de Graffigny’s Lettres d’une Péruvienne (1747), Anna Laetitia Barbauld’s “The Groans of the Tankard” (1773), Jean-François Marmontel’s Les Incas, ou la destruction de l’empire du Pérou (1777), John Thelwall’s The Incas; or the Peruvian Virgin (1792), August von Kotzebue’s play Die Spanier in Peru (1796), and Richard Sheridan’s wildly popular Pizarro (1799), an adaptation of Die Spanier performed at London’s Drury Lane.(7), (8) Across the Atlantic, a similar Andean literary renaissance was manifesting itself with the publication of Joel Barlow’s The Vision of Columbus (1787), William Cullen Bryant’s “The Damsel of Peru” (1826), Washington Irving’s Life of Columbus (1828), Robert Montgomery Bird’s drama Oralloossa (1832), a play centered on the assassination of Pizarro, and William Prescott’s History of the Conquest of Peru (1847). Amidst this wave of South American themes in European and American literature, Thomas Babbington Macaulay could indeed rightly proclaim that “every schoolboy knows who imprisoned Montezuma and who strangled Atahualpa.”

<7>By the time Peru was published, Williams not only built upon the climate of Andean literary interest in Britain and the United States, she also coincided with the Túpac Amaru Inca revolts that played themselves out on an international stage.(9) While in London, Williams and her circle followed these events in Perú through publications such as The London Magazine, The Post and Daily Advertiser, and The Monthly Repository.(10) Their foreign correspondents chronicled the bloody South American uprisings whose rumblings would later be heard in the Touissant L’Ouverture-led revolts in Haiti (1791) and the maroon rebellions in Surinam (1795). These insurrections, which had haunted Europe’s colonial infrastructure in the Caribbean, served as small-scale representations of a larger independence movement spreading itself onto a decidedly broader terrain.

To Climes Unknown

<8>Climate, it seems, whether political or atmospheric, always attracted Williams to her narrative subjects. As she discussed in her Advertisement to Peru, Williams wished to sketch the sufferings of “an innocent and amiable People” against the backdrop of their climate, which “intirely [sic] dissimilar to our own, furnishes new and ample materials for poetic description” (vii-viii). Her mapping of the Andean landscape occurs in the opening lines of Canto One with a “General Deƒcription of the Country of Peru.” The invocation, as Diego Saglia points out, remains a narrative of the past, and yet it is a “vision, in the locodescriptive mode, of atemporal beauty and peace” (212):

WHERE the Pacific Deep in ƒilence pours

His languid ƒurges on the weƒtern ƒhores,

There, loƒt Peruvia! bloom’d thy cultur’d ƒcene,

The ƒtill wave, emblem of its bliƒs ƒerene! –

There ƒmiling Nature in luxuriance ƒhowers,

From her rich treaƒures, the ƒpontaneous flowers;

The looƒe-rob’d Graces ƒpread her floating train,

And beauty bloƒƒoms as it ƒweeps the Plain,

Uncheck’d by Art, in ƒweet diƒorder wild,

As when the World was young – the Nymph a Child! (I.1-10)

The reader comes upon “loƒt Peruvia” from the sea, crossing the Atlantic to reach the shores of a land where “sweet diƒorder wild” reigns. That Williams chooses to describe Perú as “loƒt” is in keeping with the antiquarianism prescribed to indigenous territories away from the metropolis. The adjective also positions her poem within the trope of maritime discovery, for her British readers disembark, albeit metaphorically, upon the New Continent like the fifteenth-century Spanish before them. The vantage point of the sea, an ominous harbinger for the Spanish fleet by Canto Two, remains a “ƒtill” wave at the outset of the poem. Its “bliƒs ƒerene” allows for sweeping vistas of Perú’s prelapsarian splendor.

<9>Glancing at the coast towards the valleys the reader encounters an Edenic space where nature appears tranquil, pristine, and effortlessly fecund. Gendered female, Peruvia abounds in rich treasures both above and below the ground. The catalogue of riches that Williams categorizes moves vertically from the botanical descriptions of trees and plant vegetation to the taxonomy of animal species, and finally to the mineralogical composition of the earth. Williams systematically creates a textual tableau by painting a portrait of nature that is unified, harmonious, and interdependent.(11) Her descriptive and comprehensive model, in fact, anticipates Humboldt’s “Physical Portrait of the Tropics” from his 1807 Essai sur la géographie des plantes, accompagné d’un tableau physique des pays équinoxiales and the “Sketch of the Geography of Plants in the Andes of Quito” from the 1829 Personal Narrative. As Nigel Leask explains in “Alexander von Humboldt and the Romantic Imagination of America: The Impossibility of Personal Narrative” (2002), tableaus sought to represent the “experience of tropical lands in visual or verbal form for the benefit of a metropolitan public (247). In addition, tableaus, with their corresponding maps and plates, created “a ‘tropical aesthetic’ for the European mind,” displaying more vividly the “luxurious fullness of life in the tropical world” (Leask 247). Though impeded by travel restrictions to the Spanish colonies in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Britain’s ‘armchair travelers’ could be transported through striking panoramas, piercing further into the interior of the New Continent despite being rooted off the shores of the Atlantic.

<10>To paint her tableau, Williams first sketches the range of flora or “living verdure” blanketing the hill and plain. These include the ample Palm, broad Cedars, luxuriant Orange groves, silver Citrons, sweet Anana blooms, perfumed Guavas, vermeil Bark, and ambrosial Balsam. Her idiom of fruitfulness, a term Richard Grove (Green Imperialism 1995) has used to characterize the readily identifiable and often repeated language of environmental richness employed in seventeenth to nineteenth century literature, serves here to quantify the geography of plants on a different region of the globe. Grove suggests that this type of literary representation “was a product of a very real and emerging awareness of the variety and diversity of the biota of the tropics as it was becoming better known, especially via the printed world” (40). Alan Bewell has also noted that nature during the Romantic period was “first and foremost, information, a primary focus of the newly formed systems that allowed Europeans to organize, transfer, store, and display a vast amount of knowledge about the globe.”(12) Romantic natures, he adds, appeared at this time in textual or graphic form making it possible to link the far-flung regions of empire to metropolitan centers. It was the work of travel writers, natural historians, and poets that made this transfer of knowledge widely available to a host of specialized and non-specialized audiences. As evinced in her footnotes to Peru and her Preface to Humboldt’s Personal Narrative, Williams saw herself as a legatee of travel writers such as Guillaume Thomas François, abbé Raynal (1713-1896; A Philosophical and Political History 1770), William Robertson (1721-1793; History of America 1777), and Captain James Cook (1728-1799; Journal of a Voyage Around the World 1771). Their collective landscape aesthetics and naturalist observations guided her literary compass to explore the principles of nature in her writing. In the Preface Williams writes how

[T]he narratives of travellers, and, above all, the description of those remote countries of the globe, which have immortalized the name of Cook, have always had a particular attraction for my mind; and led me in my early youth, to weave an humble chaplet for the brow of that great navigator […] The narrative of Cook’s glorious career derives a peculiar charm form presenting to us new systems of social organization […]. (PN v-vi)

What she admired in Cook and later in Humboldt was their ability to present “new aspects of the variegated scenery of the Globe” (PN vi) without 1) failing to excite general interest; and 2) merely relating cold research and technical writing. Williams learned to strike this balance between aesthetic and scientific writing in her Peruvian tableau long before her collaboration with Humboldt in the 1810s.

<11>To provide a broader, more unified picture of nature, Williams next introduces the animals that toil and inhabit the land. They range from the larger beasts of burden such as the pacos (alpacas), vicunnas (vicuñas), and lamas (llamas) to the delicate “feather’d throng” of birds. Williams’s tableau classifies the visible aspects of Peruvian nature (plant and animal life) before moving underground to the mineral deposits seldom seen by the eye. At this stage of Williams’s descending botanic and taxonomic order, one wonders, however, about the ethnographic presence in nature. Where is the indigenous population that lives above the mineral world in this “favour’d Clime”? Where are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of the “blest Region”? For more than a third of the first canto Williams practices what Mary Louise Pratt has termed the erasure of the human, where the only “‘person’ mentioned […] is the hypothetical and invisible European traveler” (Imperial Eyes 125). With no intrusion from or contact with Andeans or Europeans during the “narrative scaffolding” (Pratt 51) of the poem, the landscape forms a central rather than marginal presence in Peru. It becomes the principal figure of the epic, supplanting the characters that move swiftly in and out of the first and subsequent cantos. For aside from Perú as protagonist, no other figure remains a constant force in the poem. Even as kings, queens, conquistadores, Indians, and priests pass away, the landscape remains.

<12>When the ruler of the Incas, Ataliba (Atahualpa), appears amid the expansive scenery, he too, is naturalized. As a direct descendant of the sun God (Inti), Ataliba is not only the king of a sacred Andean race, but also the embodiment of the natural world.(13) Described as a gentle spirit, Ataliba reflects the “beauteaous Region” he presides over. Williams reserves the same words of praise, “unsullied” and “mild,” to describe both. By linking Ataliba to the social and environmental realms of Perú, considerable attention is drawn to Ataliba as sovereign protector of his people as well as the landscape. And it is precisely his role as custodian of the gold and silver mines of the Inca Empire that precipitates his downfall in Canto Two, for the Spanish, under Francisco Pizarro (c.1476-1541), must seize Ataliba before appropriating the “Gems that ripen in the torrid blaze.” Ataliba acts as the physical and territorial boundary between the earth and the ore found within his kingdom. Waging an assault on the Inca king ultimately translates into a full-scale attack upon the landscape’s glittering mines.

Be Gold the Glitt’ring Bane

<13>The advent of Spain’s “horrid tyranny in the south,” as it was often referred to after the conquest, is heralded through maritime metaphors at the close of Canto One. Peruvia’s Genius equates the arrival of Pizarro and his men to a turbulent climatic disturbance whose violent formation at sea sweeps chaos across a serene space:

Thus fair Peruvia roƒe, in grace array’d,

Thus Pleasure bloƒƒom’d in her Citron Shade,

And o’er the flow’ry Plains was seen to move,

Dreƒt in the ƒmile of Peace, the bloom of Love.

But ƒoon ƒhall wake the wild tempeƒtuous Storm,

Rend her bright Robe, and cruƒh her tender form:

Peruvia! ƒoon the fatal hour ƒhall riƒe

That wakes thy guƒhing tears, thy burning ƒighs;

Each Moment on its wing ƒhall bear thy groans,

Each Gale ƒhall tremble to thy frantic moans. (I.153-62)

Having flourished under centuries of undisturbed peace through an atmosphere of national insularity, Peruvia begins to show signs of environmental subjugation at the hands of the Spanish. These changes are registered by visceral responses typically attributed to the suffering human body. The earth’s tears, sighs, groans, and moans, all palpable corollaries of its altered state, foreshadow the enslavement of the landscape under the taxing flota and mita system established by the Spanish in the late 1560s. From the arrival of the Spanish vessel to the siege of Cuzco, Williams and her characters interpret the historical events around them by reading signs of the Spanish conquest against the backdrop of a South American nature that appears in extremis.

<14>The shift in tone and rhetoric marks a radical departure from the variegated botanical garden initially extolled in the tableau. Perú as Eden transforms into a disease-laden territory, slowly consumed by an unknown illness traced to its Spanish invaders. It is a malady analogous to those introduced by European settlers in the New Continent such as smallpox, typhus, or tuberculosis. The close association between the words “conƒum’d,” “fading,” “black’ning ills,” and “gilded poiƒons” creates a toxic antithesis to the synaesthesia of sights and sounds found within Peruvia’s paradisal imaginary. By this canto’s end, Williams presents a grim, futuristic view of what Perú might become entombed beneath heaps of the “treaƒured” yet “ƒordid ore.” The burial reference symbolically aligns the fate of the landscape with the death of Ataliba in Canto Two, giving shape to the poem’s overarching theme which contends that Pizarro’s invasion fractures Perú’s national identity (the enslavement of the Incas) while concurrently wounding its environmental consciousness (the depletion of the mines). Williams develops this notion further by bridging Peru’s sentimental and anti-imperialist rhetoric in the figure of the imprisoned and weakened Ataliba. His violent demise, “In dire, convulƒive pangs he yields his breath, / And Paƒƒions quiv’ring flame expires in death” (II.309-10), serves to heighten the affective quality of the poem’s anti-imperialist rhetoric as it serves to rescript readerly attention to the plight of Túpac Amaru II, the subjugated Inca cacique, whose similar fate in 1781 would have resonated with Williams’s audience.

Peru

<15>In her epic, Williams openly rouses support for the enslaved eighteenth-century Andeans fighting for Spanish America’s independence. By collapsing a sense of linear time, she summons the political insurrections of the 1780s while anchoring Peru’s historical timeframe within the Spanish conquest of the 1530s. In a note to the poem’s sixth canto, Williams not only welcomes the rebel uprisings as markers of social and political change, but also as signs of Perú’s geocultural autonomy: “An Indian deƒcended from the Inca’s [sic] has lately obtained ƒeveral victories over the Spaniards, the gold mines have been for ƒome time ƒhut up, and there is much reaƒon to hope that theƒe injured nations may recover the liberty of which they have been ƒo cruelly deprived (94).” The accompanying canto reads

But, lo! Where burƒting Deƒolation’s Night,

A ƒcene of Glory ruƒhes on my night!

………………..

A blooming Chief of India’s royal Race,

Whoƒe ƒoaring ƒoul its high deƒcent can trace,

The flag of Freedom rears on Chili’s Plain,

And leads to glorious Strife his gen’rous Train-

And ƒee! Iberia bleeds – while Vict’ry twines

Her faireƒt Bloƒƒoms round Peruvia’s Shrines:

The gaping wounds of earth diƒclose no more

The lucid ƒilver, and the glowring ore,

A brighter glory gilds the paƒƒing hour,

While Freedom graƒps the rod of lawleƒs Power. (VI.1477-78; 1481-90)

Williams contends that Andean sovereignty under Túpac Amaru would lead to the liberation of the mines on the New Continent, for when he appeared at the Plaza of Tungasuca, Amaru categorically proclaimed an end to colonial mining in Perú. However, with over fourteen hundred working mines still operating on behalf of the Spanish Crown during the late eighteenth century, the toil of indigenous laborers remained a driving force in the Andes. Indians continued to face an enforced draft as the labor pool of mitayos(14) had changed little since the implementation of the mita system in the sixteenth century. Amaru’s execution of the royal corregidor, Antonio Juan de Arriaga, therefore meant that the territories long exploited for imperial commerce like Potosí, Huancavelica, and the Tinta province, which by 1777 were still transporting thirty thousand laborers to the mines, would finally declare their autonomy from “Iberia’s ruthless sons” (V.839). In praising Amaru and his insurrection, Williams celebrated “the greatest and most extensive Indian revolutions on the American continents” (Fisher 52). The events that unraveled in Peru would mark the end of Spain’s colonial rule in the Andes.

<16>Though appearing as a footnote to history, the mining reference permeates every aspect of Perú, since Amaru’s pronunciamiento was especially important to England and its second Empire at the turn of the century. After the loss of the thirteen colonies during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) and the succeeding ratification of the Treaty of Paris (1784), Britain’s transatlantic territories remained in a precarious balance, even as its imperial sway over Africa and Asia was fortified. Driven by a powerful desire to maintain control of its remaining transatlantic colonies while securing new imperial territories, the possibility of a sovereign South America remained of great interest to Britain, and in particular to Londoners, given the vast mercantile opportunities which the continent’s independence promised.

<17>The collapse of Spain’s dominion in the Andes would give way to Northern Europe’s access to a host of exploitable natural resources, namely gold and silver. “At the close of the cycle of the independence wars,” writes Enrique Tandeter in Coercion and Market (1993), “English investors thought that the moment had arrived for them to replace the Spanish crown as the principal beneficiary of the riches of the Americas” (223). As Spanish America began to crumble, British blueprints for the area focused more than ever on the appropriation of its seemingly inexhaustible resources. John Stuart Mill’s influential “The Emancipation of Spanish America” (1809), for example, advanced the notion of the continent’s fecundity and the possibility of bringing its riches, “as it were, to [Great Britain’s] door.” South America, Mill wrote, was a

country far surpassing the whole of Europe in extent, and still more, perhaps, in natural fertility, which has been hitherto unfortunately excluded from the beneficent intercourse of nations, is, after a few prudent steps on our part, ready to open to us the immense resources of her territory […] and of a position unparalleled on the face of the globe for the astonishing combination of commercial advantages which it appears to unite. (280)

The legend of the “spontaneous” wealth of the Americas promulgated by the Spanish during the colonial era, and which Mill proclaimed in the nineteenth century, remained a powerful, albeit misleading economic theory for speculators and investors. It stated that “Mother Nature was the autonomous generator of riches, especially in the ‘mining’ and ‘agricultural’ sectors” (Weiner 416). “Precious metals,” the myth held “were so abundant and accessible that they could be picked up by hand. Underscoring this overflowing wealth that Mother Nature provided […] the Spaniards felt that it was only “dignified” to collect gold; they left the “silver” leftovers for “Indians and slaves” (Weiner 416). Williams’s Peru makes explicit reference to the legend in Canto Four as the Spanish come across the “golden feed” of the Andean valley. Pizarro, Alphonso, and their men believe the mineral riches of the earth to be theirs through first discovery and right of conquest:

And now ALPHONSO, and his martial Band,

On the rich border of the Valley ƒtand;

The limpid Stream they quaff with eager haƒte,

The dulcet juice that ƒwells the Fruitage taƒte;

………………..

Soon as the Morning ting’d her fragrant dews

With the pure luƒtre of her azure hues;

They ƒaw the gentle Natives of the Mead

Search the clear currents for the golden feed,

Which from the Mountain’s height with ƒweepy ƒway

They bear, and on the Lawn’s calm boƒom lay ---

Iberia’s Sons beheld with anxious brow

The ƒhining Lure, then breathe th’unpitying Vow

O’er thoƒe fair Lawns to pour a ƒanguine Flood,

And dye thoƒe lucid Streams with waves of blood. (IV.749-52; 755-64)

The passage remains faithful to the Spanish chroniclers whom Williams culled from Robertson’s History, including Inca Garcilaso de la Vega’s (1539-1616) “De Oro y Plata” from his Comentarios Reales de los Incas (1609; 1617):

El oro se coje en todo el Perú; en unas provincias es en más abundancia que en otras, pero generalmente lo hay en todo el reino. Hállase en la superficie de la tierra, y en los arroyos y ríos, donde lo llevan las avenidas de las lluvias; de allí lo sacan, lavando la tierra o la arena, como lavan acá los plateros la escubilla de sus tiendas, que son las barreduras de ellas. Llaman los españoles lo que así sacan oro en polvo, porque sale como limalla. (III.95)

In these parallel seventeenth- and eighteenth-century descriptions, the gold beds appear boundless, flowing freely from the mountain streams from where they emanate. However, in Peru, Williams condemns the Spaniards’ enterprise by drawing a correlation between imperial greed and the colonization of the landscape, a modus operanti later emulated by British agents in the Andes, who, according to Edmund Temple, secretary for the Potosi, La Paz and Peruvian Mining Association, could be “seen or heard in every providence, bargaining for mines” (Travels 198-99).

<18>New avenues for transatlantic expansionism thus opened up when Spain’s legendary territorial and religious protectionism ceased to exist. According to Ángela Pérez-Mejía, “If the Spanish empire had launched its expansion under arguments of ecclesiastic providence, […] now transnational economic enterprises became the medium of colonial expansion” (4). This process, Pérez-Mejía maintains, was watched with immense commercial optimism. Mary Louise Pratt’s Imperial Eyes (1992) has estimated that during the British mining boom of the 1810s and 1820s, dozens of “mining investment companies burgeoned overnight on the London Stock Exchange as investors prepared to get rich quick” (147) through lucrative land based expeditions led by engineers, agronomists, and most notably, mineralogists. Among these speculative industries were the Franco-Mexican Association (later the United Mexican Association), the Potosí Company,(15) the Potosí, La Paz and Peruvian Mining Association, the Real del Monte Company, and the New Granada Mining Company.

<19>The desire to buy, sell, or otherwise share in the frenzy for landed property, also extended itself across the Atlantic. In 1788, Williams’s intimate friend, the American poet and politician Joel Barlow (1754-1812), traveled to Paris with Daniel Parker, an American businessman, to sell land deeds for property off the Ohio River on behalf of the Scioto Company (1787-1790), a failed commercial venture based in the United States. In A Yankee’s Odyssey: The Life of Joel Barlow (1958), James L. Woodress writes that brochures for La Compagnie du Scioto “appeared in Paris advertising the Ohio land as an earthly paradise where the soil was rich, the crops unbelievably huge, the climate excellent, and the government beneficent” (102). According to Pratt, Britain’s extractive vision for South America, which also applied to American speculations, created a literary trope she calls “industrial revery,” or romantic meditations upon mining landscapes. In one illustration, she quotes at length from Joseph Andrews’s view of the Andean Cordilleras in 1827. As a British mining envoy and engineer, he envisions the terrain before him teeming with economic energy:

Gazing on the nearest chain and its towering summits, Don Thomas and myself erected airy castles on their huge sides. We excavated rich veins of ore, we erected furnaces for smelting, we saw in imagination a crowd of workmen moving like busy insects along the eminences, and fancied the wild and vast region peopled by the energies of Britons from a distance of nine or ten thousand miles. (Pratt 150)

Here, the superimposition of nature, technology, and industry works to define a South America that is already British: at once peopled, governed, and administered by Britons, despite its ongoing battle for independence. Williams’s Amaru reference in Peru, as well as the poem’s sustained thematic focus on mining, served as a critique of this type of revery, arguing instead for an Andean landscape that retained command of its sovereign territory and its mineral deposits. With the dawn of an independent South America on the horizon, Britain’s extractive vision for the Andes was one Williams had not only intuited in the 1780s, but also resisted in the 1820s towards the end of her literary career when the Continent became the site of a reconquest led by Great Britain.

Peruvian “Tales”

<20>Williams’s view of Perú and its connection to England at the height of South America’s mining boom began to shift during her extensive collaborative project with Humboldt from 1810 to approximately 1821. The Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions, she found, was a far more statistical survey of South America than she had encountered in Robertson’s History, the main text from which Peru developed. While she was eager to participate in the translation of the Personal Narrative (“I shall never feel that the moments were misspent, which I have employed in so soothing, and so noble a task”), Williams felt ambivalent about adequately organizing and translating Humboldt’s scientific data, including the material later utilized by the capitalist vanguard. In her Preface to the first volume, Williams wrote publicly of her role as a mediator between specialist and non-specialist audiences, or those like her seeking to parse the language of science:

In becoming his [Humboldt] interpreter in the text of the Picturesque Atlas and the Personal Narrative of his voyage, I have been encouraged by the care with which he has read most of my pages, and corrected my errors. My scanty knowledge of the first principles of science seemed indeed to preclude full comprehension of many of the subjects of which he treats; but a short experience convinced me, that what is clearly expressed may be clearly understood. (xi)(16)

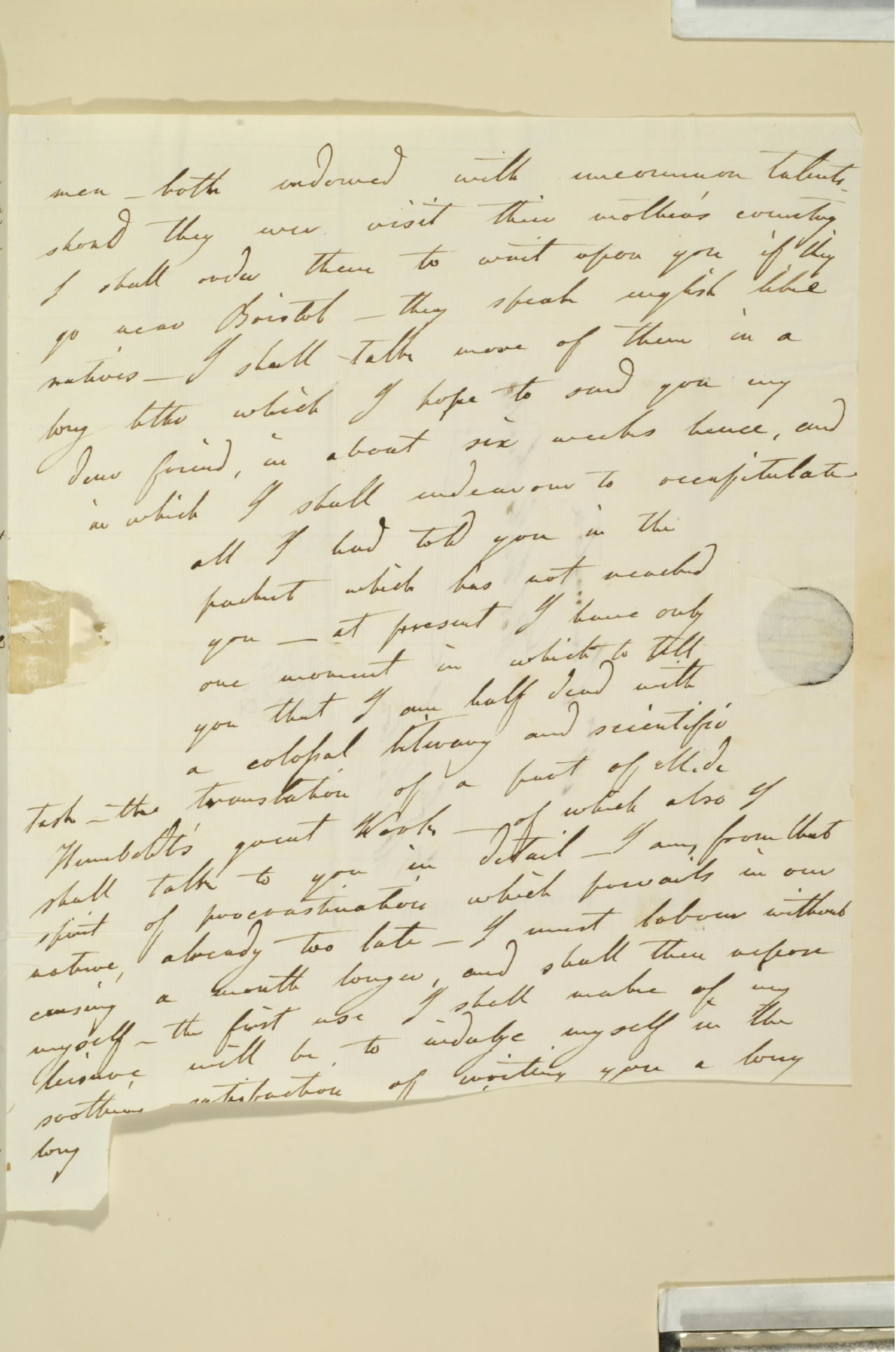

Privately, Williams was more forthcoming about the arduous task of translating Humboldt’s thirty-volume work, as evinced in a rare, undated letter to Penelope Pennington written from Paris circa 1817:

--- at present I have only one moment in which to tell you that I am half dead with a colossal literary and scientific task — the translation of a part of M. de Humboldt’s great Work &m dash; of which also I shall talk to you in detail – I am from that sprit of procrastination which prevails in our nature, already too late — I must labour without ceasing a month longer, and shall then repose myself — […](17)

The admission that she was wearied by Humboldt’s “colossal” manuscript was one which, quite literally, weighed heavily on her. This, despite having started the project with optimism and verve, and with Humboldt’s unequivocal support for her translation: “I cannot find the words that could express strongly enough the admiration with which I read these new sheets” (Kennedy 186). Like Humboldt, numerous reviewers expressed praise for Williams’s work, with the notable exception of the Quarterly Review, which continued to attack her on personal rather than literary grounds: “The natural scenery around Atures affords a specimen of the descriptive powers of our author, which however suffers not a little in the verbose and languid translation of Helen Maria Williams, alias Mrs. Stone” (367).

<21>The Edinburgh Review, however, stated that it bore “the mark of good execution” and was “the work of a lady well acquainted both with the language from which and into which her translation is made, — and who is, besides intelligent and interested in the subject about which she writes,”(18) while the Monthly Review commended her translation but regretted that she had “not deem[ed] herself authorized to take the liberty of remodelling [Humboldt’s] arrangement of materials” (15). Her preface was “marked equally by taste and sensibility” and the publication, they believed, “would have gained largely on being recast by her hands.” But as her letter to Pennington indicates, Williams found herself physically depleted the more she pierced into the interior of Humboldt’s America.(19) She became consumed by the mounting numbers of geographical, geological, and mineralogical statistics behind the Personal Narrative. For her, the role of translator and traveler coalesced as she trekked through mountains of manuscript pages detailing vast, quantifiable measurements of riverscapes, volcanoes, valleys and deserts. After Humboldt and his traveling companion, Aimé Bonpland (1773-1858), Williams would be one of the first Europeans to behold South America in such striking detail. From the heights of Chimborazo to the marshes of New Granada, Williams surveyed and classified it all.

<22>It was at this time, in the first decades of the nineteenth century, that travel narratives about the region became increasingly defined by strands of British commercialism. Williams appeared to shy away from the “hand-in-pocket” attitude (Curiosity 300) of the capitalist vanguard, or the commercially-driven travelers like Rudolph Ackermann (1764-1834), “who literally printed the bond certificates for the first major South American loans floated in London,”(20) John Taylor (1779-1863), director of the British Real del Monte silver mining company, and William Bullock (1773-1849),(21) British entrepreneur and Mexican speculator of the Del Bada mine in Temascaltepec, who were sent “by companies of European investors as experts in search of exploitable resources, contacts, and contracts” (Pratt 146). These men, among many others, had misinterpreted the mineralogical figures detailed in the publication which became “the fundamental intertext for all British and North American travel accounts concerned with Mexico […] well into mid-century” (Curiosity 263) and which played a pivotal role in the mining boom that spread through Central and South America. It was Alexander von Humboldt’s Ensayo Político sobre el reino de la Nueva España (1811).(22) The assessments made in the Political Essay regarding hundreds of Mexican mines in Guanajuato, Zacatecas, and Durango were singled out and criticized for feeding the speculative frenzy that lead the “bubble to burst” in the 1820s, affecting investors in Britain, France, and South America.(23) “The figures given by Humboldt in his book,” L. Kellner writes, “had raised the most extravagant hopes for high profits in the public” (108). While he had “acted in good faith and without any self-interest” (Kellner 110), Humboldt was nonetheless held accountable for the financial crisis that ensued. Humboldt’s Personal Narrative would also bear the brunt for providing “inflated” figures relating to the “commercial relations of the colonies and cities” (“Salon” 234) as well as the extraction of silver ores in the pre- and post-Conquest Andes. Ironically, this was the same geographical space Williams’s Peru had celebrated, in tandem with the rise of Amaru’s indigenista movement, as being free of its violent colonial mining past.

<23>Recognizing the extent to which Humboldt’s South American writings were misappropriated by the capitalist vanguard, Williams sought to distance herself from the wave of late-colonial publications of the 1820s that thematized European expansionist projects in their writings. This awareness resulted in a revised version of Peru, the Peruvian Tales of 1823, appearing in Williams’s last collected works, the Poems on Various Subjects. The collection marked Williams’s return to the world of “poetical illusion” (Woodward 191) three decades after the initial publication of Peru, and less than a decade after the Napoleonic Wars had ended. Having retreated from the public eye after Napoléon Bonaparte’s (1769-1821) Reign of Terror (1793-1794), Williams “virtually stopped publishing” for a period of ten years until after the Battle of Waterloo.

<24>The Poems on Various Subjects received favorable reviews, including one from the European Magazine of 1823 which remarked, “It is pleasurable to see the name of this lady again in print, as it recalls to our imagination the older times, when her talents were a passport for her into the society of Johnson Goldsmith, and the literary host of that memorable period” (355-56). Within her “elegant” volume, the greatest approbation was given to the Peruvian Tales: “The highest species of composition in the volume are the Peruvian Tales, occupying about sixty pages. These contain passages of fire and of pathos, and may be read with pleasure and improvement. We think the volume a very acceptable offering to the public; and it will be valued by many as a reminiscence of a lady whose name was once so familiar to our studies […]” (355-56). That the poem possessed elements of “fire and pathos” coincided with Williams’s move away from the mineralogical to focus more distinctly on the interpersonal responses to imperial expansion.

<25>This change remains most evident in two key areas: 1) the poem’s emended title, whose overarching theme stressed the narrative or story-telling aspect of its characters; and 2) the reorganization of its cantos, which introduced subheadings privileging the gendered perspectives of its female protagonists (Alzira, Tale I; Alzira, Tale II; Zilia, Tale III; Cora, Tale IV; Aciloe, Tale V; and Cora, Tale VI.).(24) Under this new structural arrangement, Perú as protagonist became subordinate to Perú as the mise en scène for the Peruvians and their stories, described as those relating to “misery and oppression” (xi). From the outset, Williams abridged the expansive landscape descriptions that had governed Peru in favor of scenes that moved quickly through nature and on to romantic vignettes of love and loss, as the following reading suggests. First, a passage from 1784’s Peru:

This beauteous Region ATALIBA ƒwayed,

Whose mild beheƒts the willing heart obey;d’

Deƒcendant of a ƒcepter’d ƒacred Race,

Whoƒe origin from glowing Suns they trace;

And as o’er Nature’s form the ƒolar beam

Sheds life, and beauty, as th’effulgent ƒtream

Of radiant light her fragrant boƒom warms,

Wakes her rich odours, and unfolds her charms,

So o’er the blooming Realm their bounties flow’d,

And thus the beams benign of Virtue glow’d

So felt the cheriƒh’d heart the genial ray

Of Mercy, lovelier than the ƒmile of Day!

In ATALIBA’s pure, unƒullied mind

Each mental Grace, each lib’ral Virtue ƒhin’d,

And all uncultur’d by the toils of Art,

Bloom’d the dear genuine offspring of the heart:

His gentle Spirit Love’s ƒoft power poƒƒeƒt,

And ƒtamp’d ALZIRA’s image in his breaƒt;

ALZIRA, pure as Fancy’s infant dreams,

Sweet as the vivid ƒmile that Beauty beams (I.71-90)

What follows is the précis from the 1823 Peruvian Tales:

There the mild Inca, ATALIBA sway’d,

His high behest the willing heart obey’d;

Descendant of a sceptr’d sacred race,

Whose origin from glowing suns they trace.

Love’s soft emotions now his soul possest,

And fix’d ALZIRA’s image in his breast.

In that best clime affection never knew

A selfish purpose, or a thought untrue

(23)

Textual variants in this and subsequent sections illustrate how social interactions were brought to the foreground, minimizing, if not altogether deterritorializing the territory of the Andes. The landscape aesthetics of Peru had no ‘place’ in the Peruvian Tales since the discourses of nature had become complicit with the project of British expansion in the Andes.

<26>In addition to these correlative changes, the Peruvian Tales demonstrated an avowed disengagement with the mining discourse once prominent in the poem’s initial structure. The language of environmental richness, now linked to British capital and enterprise, no longer drove the narrative thread from tale to tale. Passages that had hitherto referenced the mineral resources of the Cordilleras were either extracted, as in “While rich Potoƒi rolls the copious tide / Of Wealth, unbounded as the wiƒh or Pride” (VI. 1435-36), or absorbed into the broader theme of human suffering:

Peru (1784)

Ere Wealth in ƒullen pomp was seen to riƒe,

And rend the bleeding boƒom’s fondeƒt ties,

Pall with his baleful touch th’unƒullied Flower,

And cruƒh the Bloƒƒom in Affection’s Bower!

Fortune, light Nymph, ƒtill bleƒs thy sordid ƒlaves,

Still on the venal heart pour all it craves;

Bright in its view may golden Viƒions ƒhine,

And loƒt Peruvia ope each glitt’ring Mine;

And bring the Robe of Eaƒtern pomp diƒplays,

The Gems that ripen in the torrid blaze

Collected may the mingled ƒplendors ƒtream

Full on the eye that courts the gaudy beam. (I.97-108)

Peruvian Tales (1823)

Not as on Europe’s shore, where wealth and pride

From mourning love the venal breast divide;

Yet Love, if there from sordid shackles free,

One faithful bosom yet belongs to thee;

On that fond heart the purest bliss bestow,

Or give, for thou canst give, a charm to woe;

Ah, never may that heart in vain deplore

The pang that tortures when belov’d no more. (23-4)

Readers of the Peruvian Tales were discouraged from engaging in the exercise of industrial revery made popular in the 1820s when the “craving for information about Mexico [and South America]” (Curiosity 299) stimulated the commercial objectives of British speculators.

<27>Williams learned that “The business of South America” (Mill 292) continued to enslave rather than liberate Perú from the “fetters” of its Eurocolonial history, a turn of phrase she had employed in 1798’s Tour in Switzerland:

When in my Poem on Peru, one of my earliest productions, I fondly poured forth the wish that the natives of that once happy country might regain their freedom […] That Revolution had not then taken place, which appears defined to break the fetters of mankind in whatever region they are found, and which transforms what was once the vision of poetic enthusiasm into the sober certainty of expectation. (1.127)

Williams hoped that the principles of justice, liberty and equality promoted by the French Revolution would cross the Atlantic, bringing the Andeans closer to emancipation at the turn of the century. However, despite her idealism, the Andean revolt of Túpac Amaru II failed to effectuate the social, political, and economic revolution it once promised. And least of all, in the mining sector. Indeed, for nearly forty years, Williams had found Perú an intriguing prospect.

Figures